It is estimated there are more than 7,000 identified rare diseases, yet only around 400 have licensed treatments.

A rare disease is defined as affecting less than 200,000 people, but in some cases it could be as few as one or two families. Therefore, due to the smaller end-market, traditional drug-discovery financing models are often inadequate.

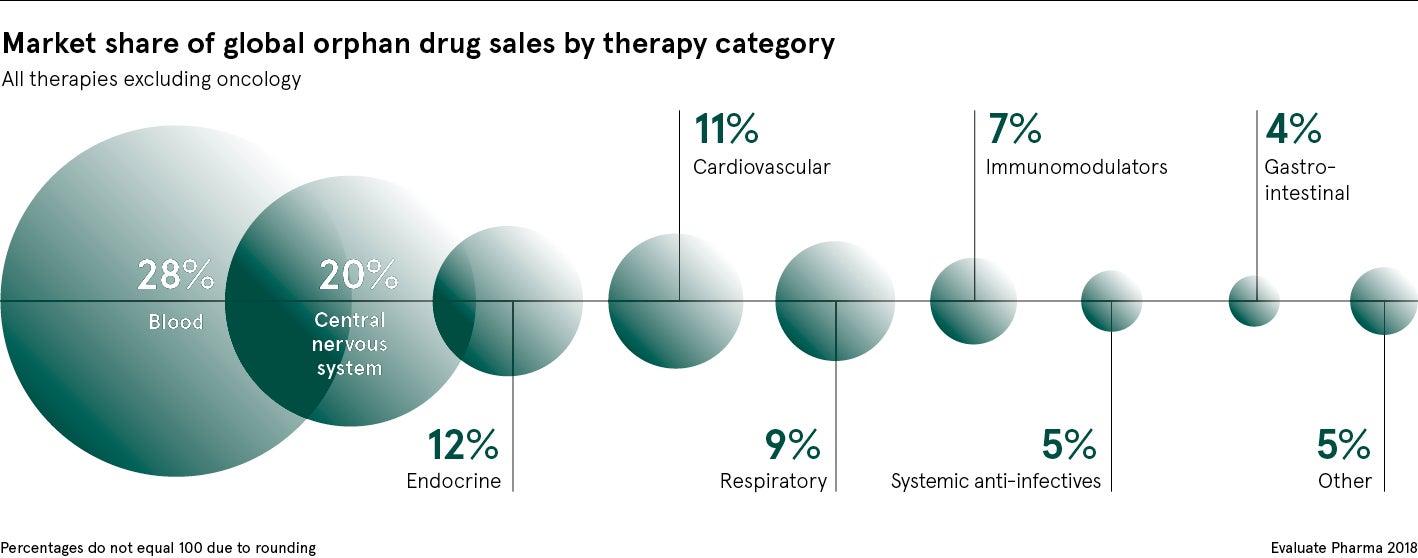

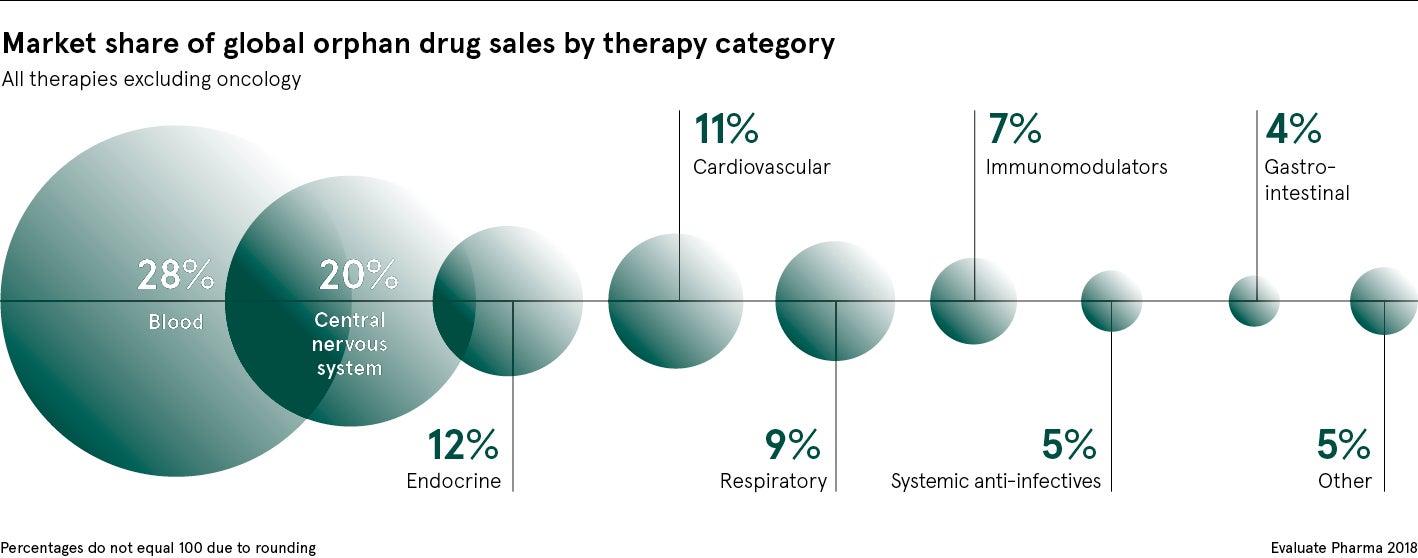

While legislation in both the United States and European Union, known as orphan drug designation, incentivises development for rare “orphan diseases” by providing a guaranteed market, it is far from a panacea.

There is a worry we get to a stage where there are drugs developed, but no one can afford to access them

Repurposing drugs could be key to rare diseases treatment

To accelerate the discovery of affordable new therapies for those living with such diseases – around 30 million people in the EU alone, according to the European Medicines Agency – new, innovative thinking and funding models are required.

One burgeoning area of activity is the repurposing of existing or in-development drugs. This means running trials and testing drugs already available on the market or taking therapies that proved ineffective in their original trials, but whose toxicity and safety record are known, and retrialling them to test their effectiveness in specific rare diseases.

Tim Hoctor, vice president of professional services at Elsevier, a global information analytics firm, says the business model to repurpose drugs is strong and compelling, particularly as ongoing research through genomics and other studies have made it easier to test for and understand the molecular detail of rare conditions.

“The more we know about rare diseases in the general population, the more we can potentially target a therapy that has already been developed, and is known to be safe, and bring it to market relatively quickly and cheaply for another disease,” he explains.

According to Global Data, drug repurposing can reduce the development cost of therapies from more than $1 billion for new chemical entities to under $50 million. It can reduce the time to market by half – five years compared to fourteen – as well as limit failure risk.

Bold new ways to secure investment

Cydan, a US-based drug discovery accelerator for rare diseases, through its spin-off company Imara, is testing a drug candidate for sickle cell, a rare, genetic blood disease. The candidate had previously been shelved by a pharmaceutical company.

“We look at firms that have molecules sitting on the shelf and spend time working out how to identify a mechanism that can work for that molecule, which has been tried for one thing, but didn’t succeed,” explains founder and chief executive Chris Adams.

Cydan, he says, have developed a unique way to secure investment for potential rare disease drug candidates by de-risking them upfront.

“Our team acts like a diligent venture capital fund, but also de-risks by defining what the ‘killer’ experiment is that could lead to an investment decision to invest,” he says. “Financiers can then, for $1 million to $2 million, get to an asset that is de-risked before they put in the further $30 million to $40 million needed.”

For example, for its sickle cell candidate, the company licensed the relevant molecule from Lundbeck at the preclinical stage and de-risked it in animal and cellular models of sickle cell. Then in 2016, the company raised $31 million to begin phase-II testing that should be completed by 2019. Cydan has spun off three companies so far, two that are still active, and is preparing for its fourth.

UK charity finds disruptive new way to tackle rare diseases funding

Drugs that are already licensed are an even cheaper source of potential therapies for rare diseases. Yet, because many of these drugs are already, or will be imminently, off patent, there is little financial incentive to retrial them for other disorders.

Fran Platt, professor of biochemistry and pharmacology at the University of Oxford, explains: “A repurposed drug could be given orphan designation, but if it is freely available, it would be difficult to enforce pricing, meaning there is a risk drug companies won’t recoup their costs.”

Findacure, a UK-based charity founded to drive research and development for rare disease treatment, wants to bypass pharma altogether.

Chief executive Dr Rick Thompson says orphan designation incentive, though good, often leads to highly priced drugs. “There is a worry we get to a stage where there are drugs developed, but no one can afford to access them,” he says.

Therefore, Findacure is proposing a radical new funding strategy: a social impact bond. The charity wants to issue a bond funded by private investors to pay for ten clinical trials for repurposed drugs, specifically targeting diseases that have a high management cost for the NHS.

In theory, successful trials would lead to off-label prescription of drugs for rare diseases within the NHS, which would then, from the saving it makes via reduced demand for surgery, care, appointments and so on, pay a proportion of money back into the bond to reimburse investors and fund new trials. The NHS has yet to agree to trial the model, however.

“I think it is a really unique and disruptive idea that proposes a different way to tackle a difficult problem,” says Dr Thompson. “It just needs more time to soak into the consciousness to the NHS.”

Findacure is currently working with US charity Cures Within Reach to help develop the idea further.

Better data-sharing could help speed up drug discovery

Unfortunately, Mr Adams believes that of the estimated 7,000 rare diseases, the addressable number is probably only 500 to 600, with the others not warranting investment, due to the size of patient groups.

However, for these smaller populations, Dr Thompson says, early-discovery work is being catalysed by patient groups themselves, even very small ones.

For example, the AKU Society, which represents the extremely rare genetic disease alkaptonuria, also known as Black Bone Disease, has been repurposing an existing drug called nitisinone, currently licensed for tyrosinaemia type 1, for treatment of the disease after animal experiments and research studies showed it could be effective.

Drug discovery for rare diseases remains problematic; orphan designation encourages investment, but results in high-priced drugs, while thousands of diseases, even with incentives, will never be commercially viable to treat.

However, experts agree that better data-sharing across all stakeholders in the sector will be pivotal in accelerating and de-risking drug discovery faster for pharma companies, charities and small patient groups by helping them find new therapy candidates from existing research and studies.

Repurposing drugs could be key to rare diseases treatment

Bold new ways to secure investment

UK charity finds disruptive new way to tackle rare diseases funding