The burgeoning rise in joint replacements is a hot topic. When Stephen Cannon, vice president of the Royal College of Surgeons, said the demand for joint replacement surgery may soon outstrip supply and the UK’s ageing population presented a “perfect storm”, few health practitioners disagreed with him.

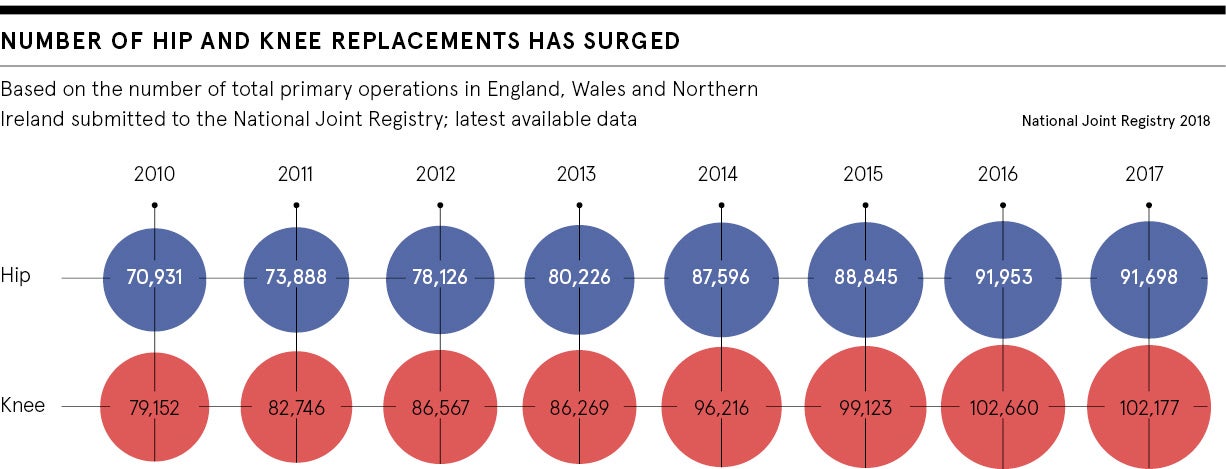

The statistics make it clear. In 2017, the number of primary hip and knee replacement surgeries in England, Wales and Northern Ireland totalled 91,698 and 102,177 respectively, based on numbers submitted to the National Joint Registry.

According to projected figures from a 2015 study published in the Osteoarthritis and Cartilage journal, the NHS will need to perform an estimated 439,097 hip replacements and 1.2 million knee replacements by 2035 to keep the population in England and Wales mobile and pain free.

A large part of the predicted demand is a result of an increasingly ageing population; by 2030, it’s forecast there will be around 15 million people in the UK over the age of 65.

So what can health practitioners do to prepare for this perfect storm?

Firstly, reconsider the timescale by which current operations are being performed. At the moment, it takes an average of 15 weeks from the point of diagnosis for a patient to be operated on for joint replacement, which falls within the NHS 18-week target. But it appears the NHS plans to relax targets.

“Any prolonged delay at the end-state of osteoarthritis will weaken the muscles and other soft tissues. Once that happens the consequences for the patient can be devastating and usually lifelong, with long-term implications for health and social care funding,” says the former president of the British Orthopaedic Association (BOA), Ian Winson.

Meanwhile, in the winter, delays can be even longer. John Skinner, consultant orthopaedic surgeon and treasurer of the BOA, says a key thing the NHS can do to increase efficiency is guarantee a given number of operations, all year long, come what may.

“A problem we’ve had for several years now is the fact elective orthopaedics surgeries are the first cancelled when it snows in December. That is something that will need to change if demand is to be met,” he says.

The second issue is minimising the amount of time any patient who has had a successful operation needs to stay in hospital, while guarding against infection following surgery.

Although surgery is certainly an end to the pain people with arthritis learn to endure, even a successful operation comes with its own problems. As chief executive of Orthopaedic Research UK Arash Angadji explains: “If you talk to the people that have had surgery, 30 per cent are unhappy with the outcome. The pain may have gone away, but many are realising you cannot kneel to do gardening and you can’t lift your grandchild.”

It’s for this reason that using top-end materials, namely ceramics and new polyethylenes which make the best implants, is important. While traditionally they have been reserved for younger patients because of their cost, with future patients expecting to rely on an implant for around 40 years, durable ceramic will be the material of choice.

“Currently 45 per cent of joint replacements last ten years,” says Mr Skinner. “Given that increasing numbers of people will now live to 100, we want joint replacements that are going to last 40 years.”

But it’s important that any new manufacturers reach a standard referred to in the industry as “beyond compliant”, particularly after the 3M Capital Hip implant controversy in the 1990s, which led to the creation of the National Joint Registry to oversee the quality and performance of implants.

Of course, the best implants are expensive. Currently the average joint replacement costs the NHS between £5,000 and £11,000. As such allocating appropriate funds will be a big factor in ensuring demand is met, particularly as in 2018 The BMJ reported that the NHS was unable or refusing to operate at an increased rate of 45 per cent.

“There have been too many issues with clinical commissioning groups finding funding,” says Mr Skinner. “That will have to change.”

In the meantime, perhaps the best preparation is prevention. After all, the key to protecting joints and heading off surgery altogether in older age starts when young. While general wear and tear is inevitable, keeping active and maintaining a healthy weight are vital in minimising long-term damage, and the risk of needing knee and hip joint replacement surgery.

Both Dr Angadji and Mr Skinner single out obesity as the most manageable factor in preventing joint replacement.

Dr Angadji sees promise in smart health technology and the internet of things. “An implant that tells you when to move, when to rest, when you’ve done enough impactful sport for the day could play a vital role in both promoting the health of the patient and longevity of the implant. Ultimately, having more information will make patients more personally responsible,” he says.

But personal responsibility can only stretch so far when part of the problem is that we still don’t know what causes arthritis. While illnesses such as cancer and Alzheimer’s disease have been prioritised for research funding, further study of the causes, prevention and possible cure for arthritis should be a valuable investment.

As Dr Angadji concludes: “Being mobile is vital for patients with comorbidities; your chance of beating diabetes, mental health issues or a heart problem is zero if you can’t move.”