Early detection can make all the difference when treating skin cancer. Consequently, the number of skin diagnosis and mole monitoring apps has multiplied over the past five years. A 2017 study, for instance, found there had been an 80.8 per cent growth in dermatology apps since 2014.

But do such telemedicine apps create more problems than solutions? Or can sophisticated, regulated technology, artificial intelligence (AI) and telemedicine products streamline patient pathways and ease the burden of healthcare professionals, detecting more cases of malignant melanoma?

Healthcare professionals overstretched

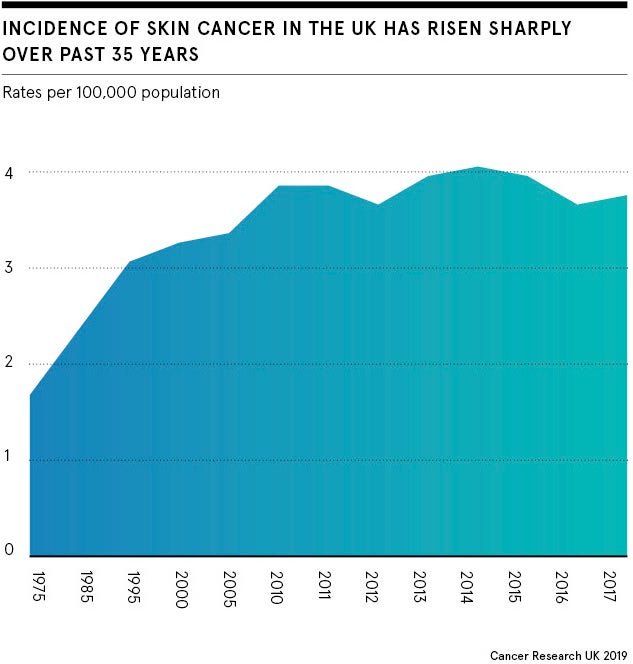

Skin disorders are extremely common and the number of people who develop malignant melanoma in Britain has risen faster than any other common cancer. Between 2013-14 and 2017-18 GP referrals for dermatology increased by 15 per cent to 1.16 million a year, according to NHS England.

The coronavirus pandemic has meant many routine screenings, and urgent referrals and treatments, have been delayed or cancelled, leading to a backlog of patients.

With so many moles referred from primary care, which usually require a biopsy, malignant melanoma is notoriously time intensive and challenging for doctors to diagnose.

How telemedicine can help

Telemedicine has been hailed as a solution. Skin diagnosis and monitoring apps, such as Skin Analytics, Miiskin or MoleCare, present an opportunity to clear the backlog of patients created by the pandemic and could make it possible to catch additional skin cancers early on.

Neil Daly, chief executive of Skin Analytics, believes there is “no answer that doesn’t involve technology like ours”. He says: “We just don’t have the resources to cope with the number of patients otherwise.”

The rise in commercial skin diagnosis apps could reflect an increased desire for patients to take healthcare into their own hands, especially in light of COVID-19. “It’s empowering for the patient because it enables them to take control of their own health,” says Dr Sharon Wong, dermatologist based at London Bridge Hospital.

However, there are concerns about unregulated commercial apps diagnosing and treating skin cancers and skin conditions.

As dermatologists we will and we should move along with how technology develops. AI will be the way forward and we do need to adapt our ways accordingly

John Loder, investment director for Nesta, an innovation foundation, is optimistic about the potential of sophisticated telemedicine technology, but says it must be properly regulated and tested in clinical settings. “The regulatory environment is not completely nailed down,” he says.

A BMJ report released in February looked into publicly available skinScan and SkinVision apps, and concluded algorithm-based smartphone apps had a “poor and variable performance”, saying “these apps have not yet shown sufficient promise to recommend their use”.

Challenges with app-based healthcare services

If telemedicine solutions don’t have a high degree of accuracy they could cause additional problems, such as missing cancers and offering false reassurance or further overloading healthcare professionals.

“If a patient goes to a GP and says this app says this, it’ll be difficult for the GP, who is not a skin expert, to disagree. So we could get more patients referred to the dermatologist, which could even increase the workload,” says Dr Adil Sheraz, consultant dermatologist and British Skin Foundation spokesman.

On top of this, images patients take themselves on smartphones might not be clear, so apps could miss problems.

Another concern is that a lot of the images in app databases are from lighter skin types. “So they could widen the gap we already have in picking up melanomas in darker skin types,” says Sheraz. “We have to be careful to cater for all different types of skin cancers.”

Where it’s used, telemedicine works best alongside healthcare professionals. One reason for this is the emotional element of diagnosing cancer and need to reassure patients, says Daly at Skin Analytics. “People are really complex and AI is a blunt tool that you need to target in the right way,” he says.

For example, Wong says if a patient of hers had a lesion that looked concerning, she could prime them for the possibility of bad news early on.

Dermatologists can also examine patients physically. “Ultimately humans will prefer to have human interaction and AI isn’t able to engage in that higher-level conversation,” she says. “As a human we can examine not just on a visual aspect, but also on a tactile aspect. We can touch the skin.”

Health services of the future

Despite the misgivings, many in public healthcare and digital health are excited about the possibility of telemedicine and envision a future where skin diagnosis apps work alongside clinicians.

Digital solutions can reach remote locations and people unable to access services due to the coronavirus pandemic. Both Wong and Sheraz say they believe skin monitoring apps, such as Miiskin, are already helpful and would like to work with more regulated, sophisticated digital tools in the future.

“As dermatologists we will and we should move along with how technology develops. AI will be the way forward and we do need to adapt our ways accordingly,” says Sheraz. “I’m really happy people are looking at this technology.”

Wong agrees. “During COVID we’ve used teledermatology a lot and it’s only pushed to the forefront the importance of embracing and working alongside technology to improve patient care,” she says.

Telemedicine has the potential to streamline healthcare services and help dermatologists to detect skin cancers. But there are still a number of challenges that must be overcome to ensure the range of skin diagnosis apps are regulated, sophisticated and safe to use.

Speeding up skin cancer detection

Scientists have warned there could be thousands of excess deaths in the UK in the coming years due to delays in cancer diagnosis and treatment during the coronavirus crisis.

To tackle this, University Hospitals Birmingham (UHB) NHS Foundation Trust launched a pilot in May with artificial intelligence (AI) company Skin Analytics.

Services were set up away from the hospital and the trust’s clinical photographers worked with Skin Analytics to capture an image of the patient’s lesion which was then assessed by the AI. If it was determined to be cancerous, a dermatologist remotely reviewed and placed the patient on the correct treatment pathway.

The aim of the pilot was to reduce delays in skin cancer detection and treatment during the pandemic by providing a screening programme using the AI tool.

“It was driven by the demand caused by COVID,” says Neil Daly, chief executive of Skin Analytics. “We wanted to deal with a volume of patients that couldn’t be seen in hospital and we were able to see a large number of patients and take some of the pressure off.”

Nick Barlow, director of applied digital health at UHB, says he is “incredibly proud” of the initiative. “Identifying patients with melanoma [during the coronavirus pandemic] and providing treatment sooner will result in significant benefits,” he says. “Managing the clinical risk and finding the patients who need treatment for melanoma will also be a key focus for hospitals well beyond the COVID-19 crisis.”

The pilot is an example of how sophisticated AI-based tools can be used alongside healthcare professionals to help detect skin cancers, especially in light of the pandemic.