“Cancer is an umbrella term for thousands of different types of conditions, yet treatment offered today is often generic and does not consider the need for differing therapies for different people,” says Professor Toby Walsh, a leading expert in artificial intelligence (AI).

“However, with AI, all of us can have access to the best experts on the planet to get the best diagnosis and treatment.”

Major technology companies such as Alphabet’s Verily and Google’s DeepMind, alongside a slew of startups, are using cognitive computing to fight cancer by building tools that essentially sort and accumulate medical knowledge and data on a scale that is impossible for humans alone to achieve.

Using machines to encapsulate the knowledge of physicians and experts, and to interpret data better than the specialists, can create a new understanding of cancer to provide better diagnosis and treatment outcomes.

For example, opportunities provided by genome sequencing can be unlocked with AI. The cost of sequencing someone’s genome, which is the unique arrangement of their DNA, is falling and can now be done in 24 hours for $1,000.

Using machines to encapsulate the knowledge of physicians and experts, and to interpret data better than the specialists, can create a new understanding of cancer to provide better diagnosis and treatment outcomes

Analysing a patients’ DNA enables doctors to understand the type of cancer they have and, importantly, to act on the molecular code of the disease for more accurate treatment.

But there is no standardised approach to handling the high-volume, high-quality data produced from genome sequencing. It can differ from one hospital to another.

Swiss startup SOPHiA Genetics has developed AI that takes raw genome data and studies it to decipher the molecular profile of a person’s cancer to find more suitable and personalised treatment options.

“This technology allows doctors to understand what is driving the cancer and to tackle it with the medicine which best treats the cause of the molecular event that is no longer working,” says the company’s chief executive Jurgi Camblong. The more data analysed by the AI, the more it learns and the more powerful it becomes.

By 2020 the company, which currently has partnerships with five UK healthcare institutions, including Oxford University Hospital, wants to start collecting data on treatment outcomes, so it can identify how a specific strain of cancer responds to different treatments to determine which is most successful.

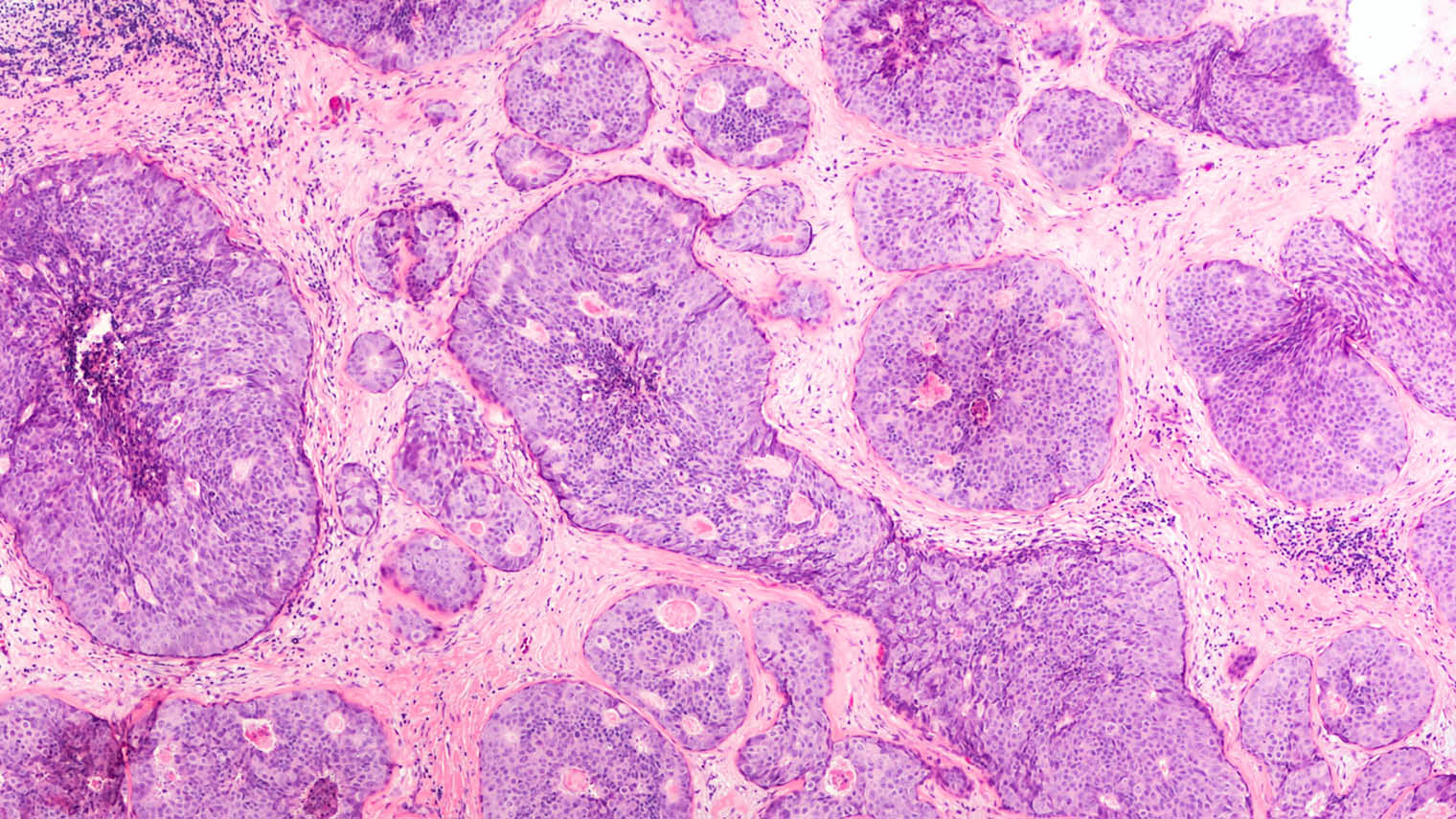

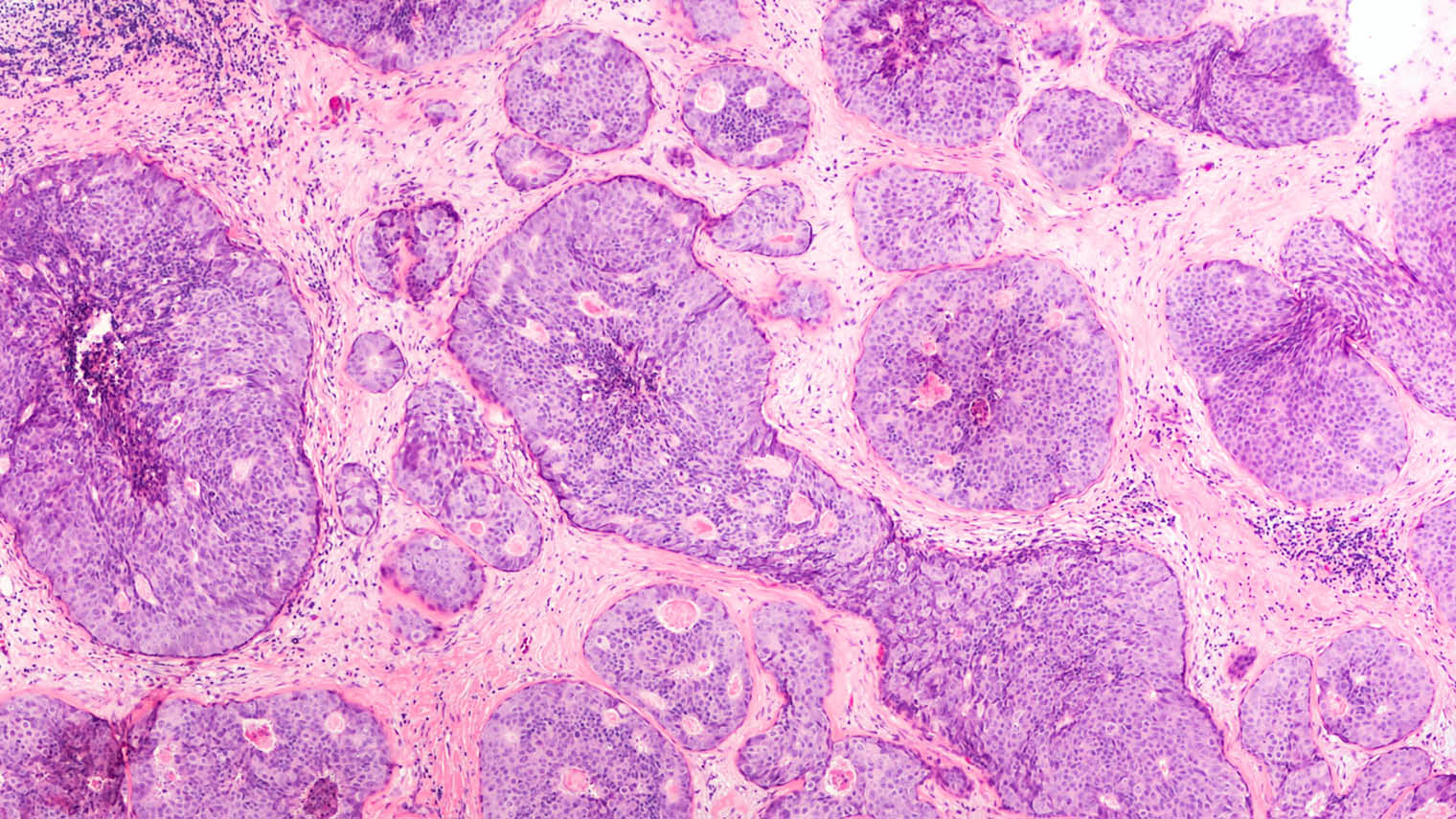

Ductal carcinoma in situ shown in a breast cancer biopsy

US-based Guardant Health has also used AI and DNA sequencing to commercialise the first comprehensive genomic liquid biopsy.

The blood test, developed by borrowing concepts from algorithms and digital communication, can unravel genetic sequences of a patient’s cancer to categorise its sub-type without the need for a physical biopsy. By repeated tests, the cancer, which is continually evolving and changing, can be easily monitored so treatment can be adapted accordingly.

Furthermore, by combining machine-learning and advances in object detection in computers, algorithms can now routinely diagnose medical images, faster and more accurately than a radiologist, which could reduce waiting times and provide cheaper and earlier diagnosis.

For the last two years, the Royal College of Radiologists has highlighted a desperate shortage of imaging doctors, making delayed scan results routine for NHS patients.

“Two billion people are joining the middle classes worldwide and will at some point need a medical scan, but there are not enough doctors to diagnose those scans; therefore we need to get help from our friends, the computers,” says Eyal Gura, co-founder and chairman of Zebra Medical Vision.

The company trains algorithms using medical images, diagnosis information and patient outcomes to detect specific diseases in scans. The algorithms are made available on a desktop AI assistant for radiographers to make a diagnosis from a scan quickly and easily.

Zebra’s algorithm trained to detect breast cancer can identify the disease at a higher accuracy rate (92 per cent) than a radiologist using computer-aided detection software (82 per cent).

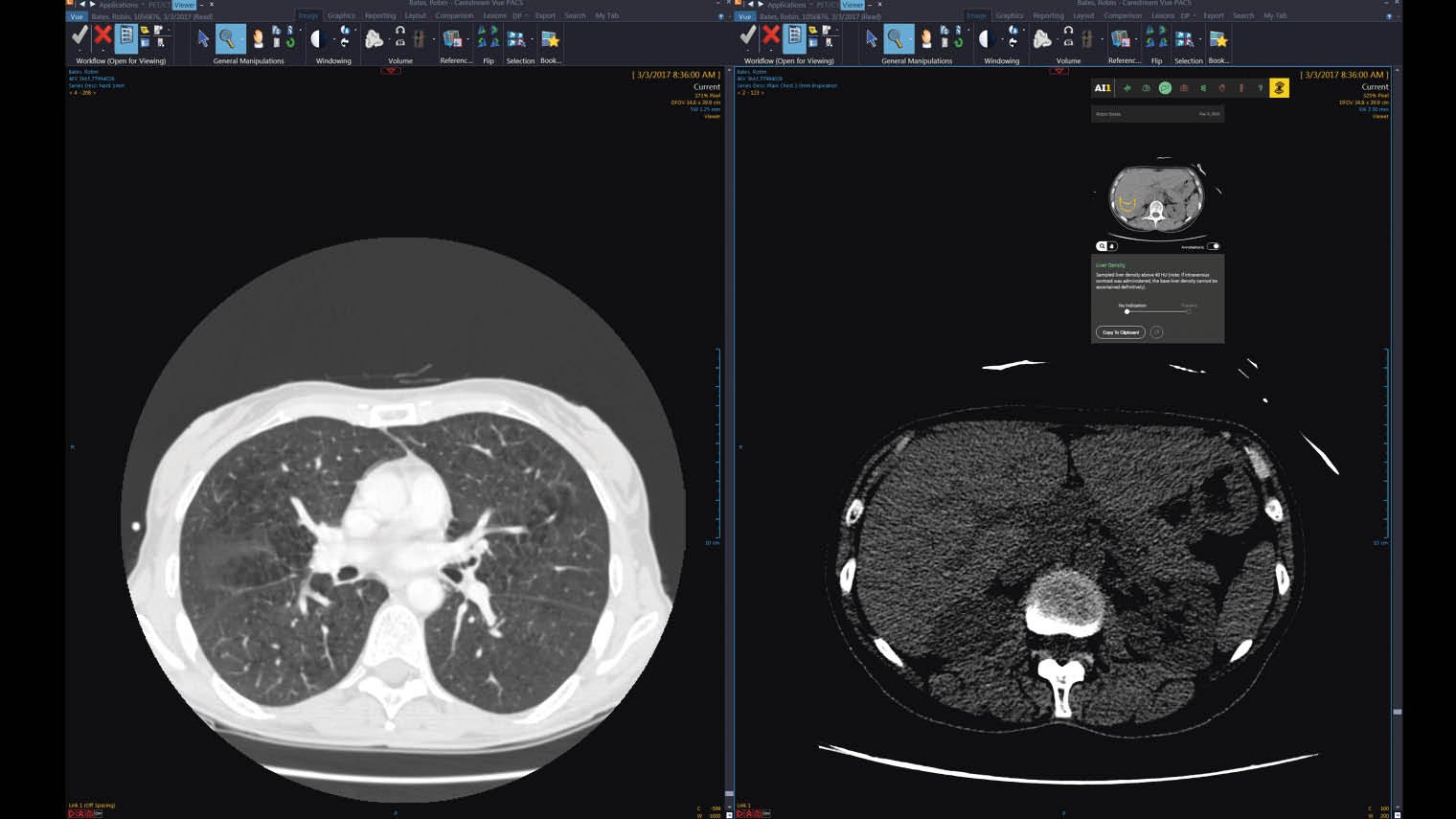

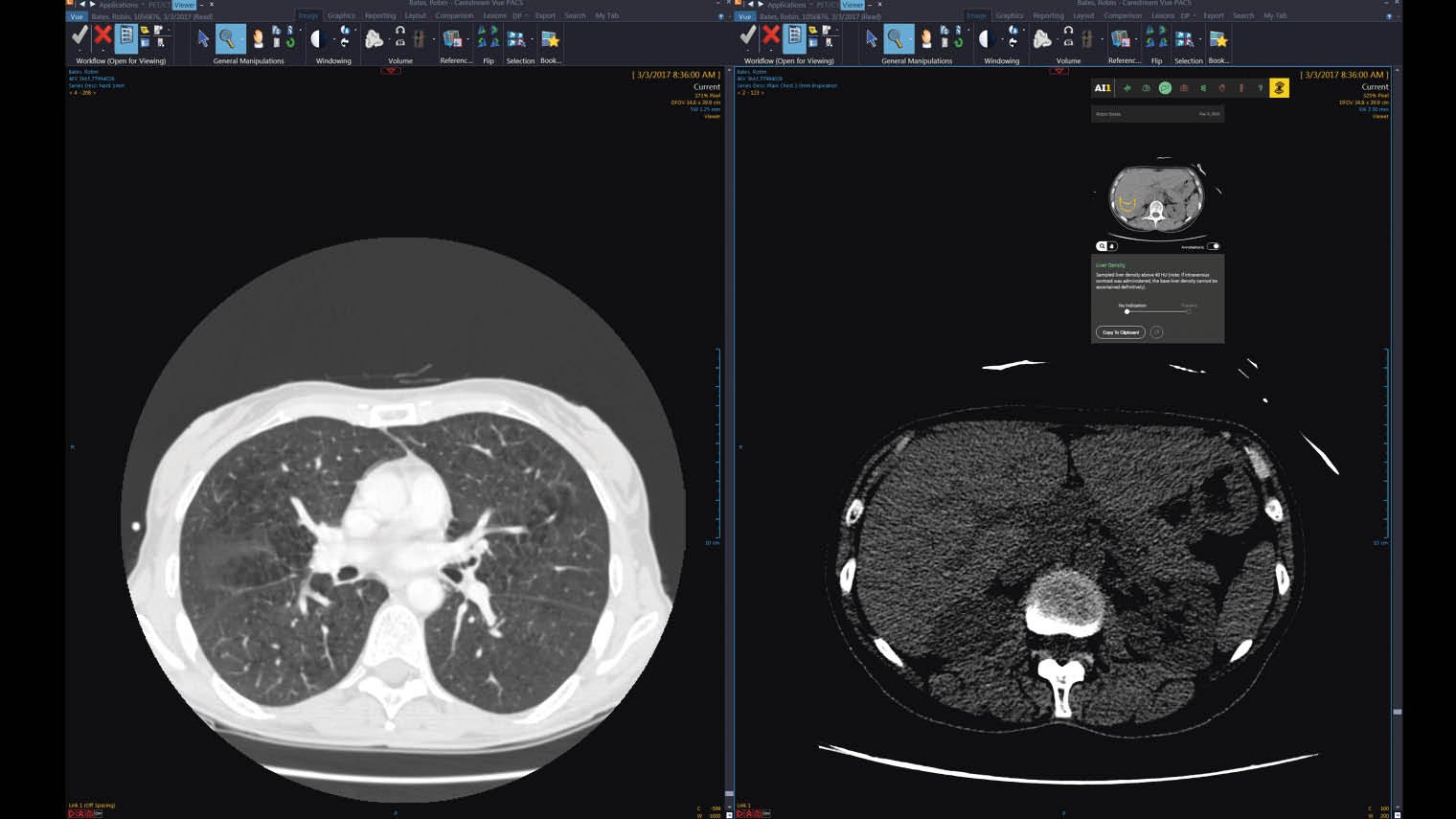

Zebra medical trains algorithms using medical images, diagnosis information and patient outcomes to detect specific diseases in scans; this image is a scan of a liver

To keep costs low, the company, which is currently working with the NHS in Oxford to test the technology, launched AI1, a new suite that offers all its current and future algorithms to healthcare providers globally for only $1 per scan.

Google’s DeepMind is doing something similar, training AI on a million anonymised eye scans from patients at various stages of age-related macular degeneration at Moorfields Eye Hospital, London.

But obtaining good-quality data in healthcare can be a problem. In November, the House of Lords heard from Julian Huppert, chair of the independent review panel for DeepMind Health, how data-sharing in the NHS presents huge challenges, and needs to become more digital and centralised as currently different trusts use varying systems that do not work together. This is perhaps why the NHS has been slow to take up AI technology.

Professor Walsh, author of Android Dreams: The Past, Present and Future of Artificial Intelligence, says the NHS is currently “not being proactive about using the technology in a proper way”. He refers to data breaches that occurred when London’s Royal Free Hospital handed over personal data of 1.6 million patients to DeepMind.

Incorporating the use of AI into the healthcare system must be done properly. Protocols, procedures and even adequate competition must be established, so large technology conglomerates do not monopolise patient data.

But it’s clear we are barely scratching the surface of what can be achieved with cognitive computing in healthcare. There is no doubt that AI has the potential to transform cancer patient care, with the ultimate goal of using computers to take first-world healthcare into the third world at an affordable price.