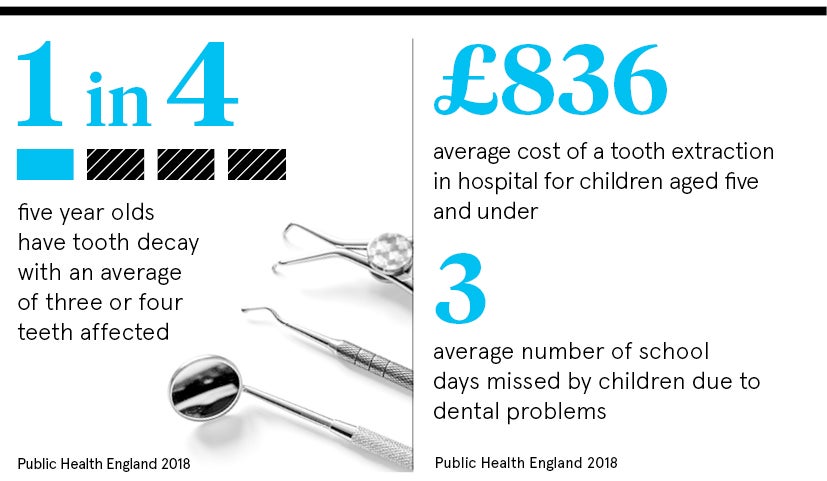

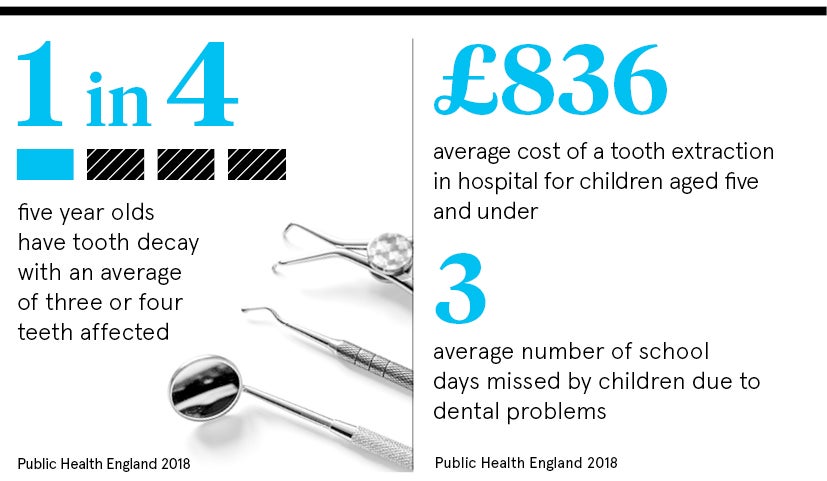

There are times I have cried after taking 20 teeth out of a four-year-old’s mouth,” says Sandra White, national lead for dental health at Public Health England. “It is sadness about that child’s future, as well as the inequalities around dental decay, and its social and health impacts.” Despite tooth decay in children being entirely preventable, it is the leading cause of hospitalisation for them in this country, while globally around 486 million children suffer.

In addition to the pain, potential infection and missed school that can go with tooth decay, children are more likely to continue with poor dental health into adulthood.

Although local authorities have a statutory responsibility to improve oral health in their areas, national policy also plays a key role, along with nurseries, schools and consistent evidence-based messaging.

1 in 8 three year olds already showing sign of tooth decay

Preventing tooth decay in children has to start early, says Claire Stevens, NHS consultant in paediatric dentistry at the University Dental Hospital of Manchester.

“One in eight three year olds already has signs of decay, so we need to be promoting this before school,” says Dr Stevens, who represents the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD). “We need to look at what happens from conception: what advice is a mum getting during pregnancy, are health visitors encouraging families into dental surgeries?”

The BSPD’s Dental Check by One campaign, supported by NHS England’s chief dental officer, aims to get all children seen by a dentist before their first birthday. The idea is to get youngsters used to an oral health routine from when their first baby teeth come through at a few months old.

Meanwhile, the new NHS Long-Term Plan, launched earlier this month, outlines an ambition to target more young children through its Starting Well core initiative, a programme which initially aimed to improve oral health in 13 priority areas.

“We need to ensure the profession all deliver the same message and ideally you would have supervised brushing in all nurseries,” adds Dr Stevens. “Some people will say ‘Isn’t that a bit nanny state?’ and in an ideal world all children would have their teeth brushed at home twice a day, but that doesn’t always happen.”

Community initiatives key to better dental health in children

Communities are grasping the nettle, with results that show a difference. In Blackpool, 46 children’s centres, nurseries and childminders carry out supervised brushing each day, while primary schools provide fluoridated milk to pupils.

“The children love the supervised brushing and are taking a proactive approach to brushing their teeth at home,” says Alan Shaw, public health practitioner at Blackpool Council. In the first two years of Blackpool’s programme, tooth decay in five year olds dropped from 42.5 per cent to 24.9 per cent, just above the national average of 23.3 per cent.

In the London Borough of Brent, a similar programme was so successful it has now been extended, with more than 3,000 children receiving free toothbrush and toothpaste kits and supervised brushing sessions.

Meanwhile, Leicester City Council’s Healthy Teeth, Happy Smiles programme pledges to give all children, by the time they are five, five oral health packs, containing toothbrushes, fluoride toothpaste and information for families.

National effort to prevent tooth decay needed

But there is a lack of consistency across UK regions, with national schemes in Scotland and Wales, but no single co-ordinated approach in England.

British Dental Association chair Mick Armstrong explains: “Deep inequalities are persisting and we shouldn’t accept that a child born in Pendle will enter primary school with 20 times the levels of decay as one born in Surrey.

“Prevention is better than cure, but we are still waiting for a dedicated, national effort to end the scandal of childhood decay.”

Oral Health Foundation chief executive Nigel Carter agrees there needs to be “a commitment to greater financial investment by the government” for a significant impact. While region-wide schemes such as water fluoridation have cut tooth decay, as well as being widely used in other countries such as the United States, the policy can be controversial despite evidence of its efficacy.

Public Health England’s Ms White says the simple mantra “less sugar and more fluoride” is the cornerstone of success.

The body’s latest Change4Life campaign focuses on sugar reduction, but is “realistic about encouraging baby steps rather than saying your child can only have carrot batons as a snack”, she points out.

However, the introduction of the sugar levy on soft drinks is a positive step and “must now be rolled out to other sugar-based drinks and confectionery”, adds Mr Carter.

Digital media and tech could promote better dental health

Experts agree that digital media could prove a major force for delivering the dental health message, as mobile phone usage booms.

The new NHS Digital Apps library includes the Brush DJ dental app aimed at children, and plans are under way to develop content with television doctor and star of Strictly Come Dancing Ranj Singh, with a series of videos optimised for social media expected to go live in the coming six months.

Meanwhile, YouTube sensation The Singing Dentist parodies popular music with his own dental health-driven lyrics, with the videos receiving up to three million views each.

Augmented reality has also hit the dental sphere, with Colgate launching its Magik toothbrush developed by French firm Kolibree to make brushing more fun using a connected app and games.

Ultimately, improving dental health is about tackling societal inequalities, stresses Dr Stevens. “Geographical differences and socio-economic issues have an impact, with determinants like poverty levels and financial inequalities,” she concludes.

“The focus nationally is to raise a generation of children free of tooth decay and we can’t just continue to do things in the same way. We have to look at tackling things in a holistic way.”

1 in 8 three year olds already showing sign of tooth decay

Community initiatives key to better dental health in children