When Josh Horrobin, now ten, was born, he didn’t open his eyes at all. Doctors initially thought he had conjunctivitis, a common eye infection in children. But to his parents’ increasing alarm, his eyes remained firmly shut. Three weeks later, they took him to A&E.

Currently around 50 per cent of children undergoing genetic testing in the UK won’t get a confirmed diagnosis

Josh’s mother, Wendy Horrobin, a former teacher of English as a foreign language and educational project manager, recalls: “The registrar in A&E shone a light in his eyes and said: ‘His eyes are not responding to the light. I don’t think he has any vision’. It was shocking. The first thing I did was to phone my husband Simon; your first thought is what can you do for your child.”

Ultra-rare disease support networks are vital

“A more detailed examination a week later revealed that his retina was completely detached and disorganised, suggesting Norrie disease. The diagnosis was confirmed after extensive investigations and genetic testing.”

A genetic condition causing either blindness or severe visual impairment from birth and progressive hearing loss in later childhood, Norrie disease is an ultra-rare disease that can also produce cognitive impairment or autism.

There is no effective treatment and there was, when Josh was born, little publicly available accurate information, which is typical of many ultra-rare diseases. “There was no dedicated UK support group. A lot of information on the internet was incorrect. We were told not to believe everything we read,” says Wendy.

“It was very isolating, but there is this desperate urge to understand what your child is dealing with. Any inaccurate information you come across compounds this feeling of isolation, as did the fact that we did not know of any other children with Norrie disease.”

Like many other parents with children with an ultra-rare disease, Wendy filled the information vacuum by co-founding a parent-patient support group, the Norrie Disease Foundation. She says: “It is impossible to underestimate the importance of mutual family support. Affected families afflicted by ultra-rare diseases really understand one another; you just cannot get this kind of support elsewhere.”

What is an ultra-rare disease?

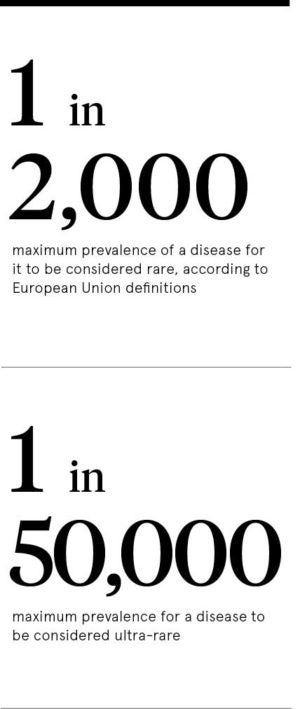

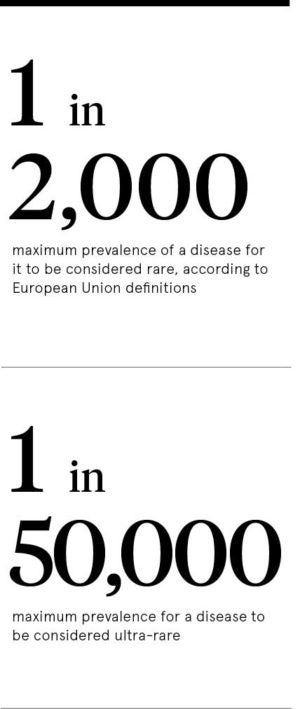

It is easy to see why so little is publicly known about ultra-rare diseases. While the European Union definition of a rare disease is one affecting fewer than five people per ten thousand of the population – or one in two thousand – an ultra-rare disease is classified as affecting one person in fifty thousand or fewer. Most ultra-rare diseases affect as few as one in a million people or less.

It is easy to see why so little is publicly known about ultra-rare diseases. While the European Union definition of a rare disease is one affecting fewer than five people per ten thousand of the population – or one in two thousand – an ultra-rare disease is classified as affecting one person in fifty thousand or fewer. Most ultra-rare diseases affect as few as one in a million people or less.

How is an ultra-rare disease identified and classified? Professor Raoul C.M. Hennekam, who has two ultra-rare diseases named after him, explains: “What usually happens is that a doctor publishes a paper about a patient with unusual signs and symptoms they do not recognise.” A single report about just one patient is not enough to secure an ultra-rare disease classification. An additional report about a second or even a third patient is required.

Professor Hennekam, who worked at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH), adds: “The author of the report describing the second or third patient then recommends that the condition should be named after the first author.”

Latterly professor of paediatrics and translational genetics in Amsterdam, Professor Hennekam says support groups have a fundamental role to play in promoting research into the causes and treatment of ultra-rare diseases. Every affected family is a potential research subject. The Norrie Disease Foundation has 40 affiliated UK families. Globally there are 500 known affected families.

“In the vast majority of rare disorders, there are sufficient numbers of patients to test treatments. For example, in a trial you can give one group of patients an active medicine and a second group a placebo – a chemically inactive substance – to see if there is a significant difference. This can be hard in the case of ultra-rare diseases because there are so few patients,” he says.

The uphill battle for diagnosis and treatment

Within the context of conventional medical research, with trials involving thousands of patients, 40 families is an extremely small investigative base, but it is the impetus behind a three-year research programme at University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health. The aim is to increase understanding about when and where hearing loss in Norrie disease occurs and to investigate possible therapies to improve quality of life.

The challenge is daunting. For example, of 7,000 identified rare diseases, only 400 have a licensed treatment, according to the Cambridge-based charity Findacure, which works with healthcare professionals and unites patients and parents with rare conditions.

For every identified ultra-rare disease, many others are unclassified. The charity SWAN UK (Syndromes Without A Name) estimates that 6,000 children are born in the UK each year with genetic conditions so rare that they cannot be named. No diagnosis means no prognosis and no evidence-based treatment.

SWAN UK says: “Currently around 50 per cent of children undergoing genetic testing in the UK won’t get a confirmed diagnosis. It is thought that about half of children with learning difficulties and approximately 60 per cent of children with congenital disabilities do not have a definitive diagnosis to explain the cause of their difficulties.”

A definitive diagnosis may lead to the reclassification of a syndrome without a name into an ultra-rare disease. In turn, as in the case of Norrie disease, this can help to identify a stream of patients which in turn can create a new research platform. Global collaboration is helping to boost the numbers of patients available for research. The Norrie Disease Foundation, for example, is working with GOSH to establish a trans-European Norrie disease patient registry. This may ultimately help young patients like Josh towards a better future.

Ultra-rare disease support networks are vital

What is an ultra-rare disease?