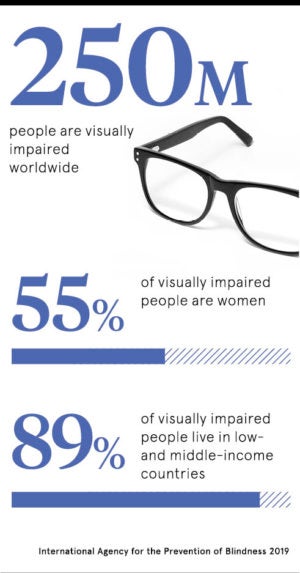

Clear vision isn’t a birth right for all mankind; it’s a privilege and so is the ability to correct poor sight. More than two billion people wake up every day with an eyesight problem and 254 million, many in the developing world, are visually impaired. From blindness to cataracts, eye diseases to glaucoma, the healthcare of our most vital of senses is a challenge, even when many conditions are treatable.

“Ultimately, we will all need eyecare at some point in our life. Eye health should be universal. The good thing is that there’s been a transformational shift in recognising that we have a significant global population health and eye issue,” explains Peter Holland, chief executive of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB).

Setting sights on universal eye health in 2020

20-20 vision for all humanity was part of Vision 2020, the brainchild of the World Health Organization (WHO) and IAPB. Launched two decades ago, along with a series of more recent action plans, the aim has been to eliminate avoidable blindness, adopt universal eye health and cut visual impairment by the end of this year, with the backing of countless governments worldwide.

“The year 2020 due to its cultural positioning has been an automatic goal for all vision initiatives since the 1990s. All global vision efforts have been working towards this point for close to three decades,” says Selina Madeleine from the Brien Holden Vision Institute. So how far have we come?

Grand figures are hard to come by, although the IAPB’s Vision Atlas helps. However, all eyes are now on a new and long-anticipated study, the World Report on Vision from WHO, which is the first of its kind to be released by the Geneva-based global body. Out this autumn, it will be the definitive document for professionals worldwide and is expected to set the agenda for universal eye health in the decades to come.

“We’re excited about its launch,” says Dr Alarcos Cieza, WHO co-ordinator for blindness prevention. “There has been considerable effort over the last 20 years to address eye conditions and vision impairment, and this has resulted in many areas of progress.”

How to tackle eye disease globally

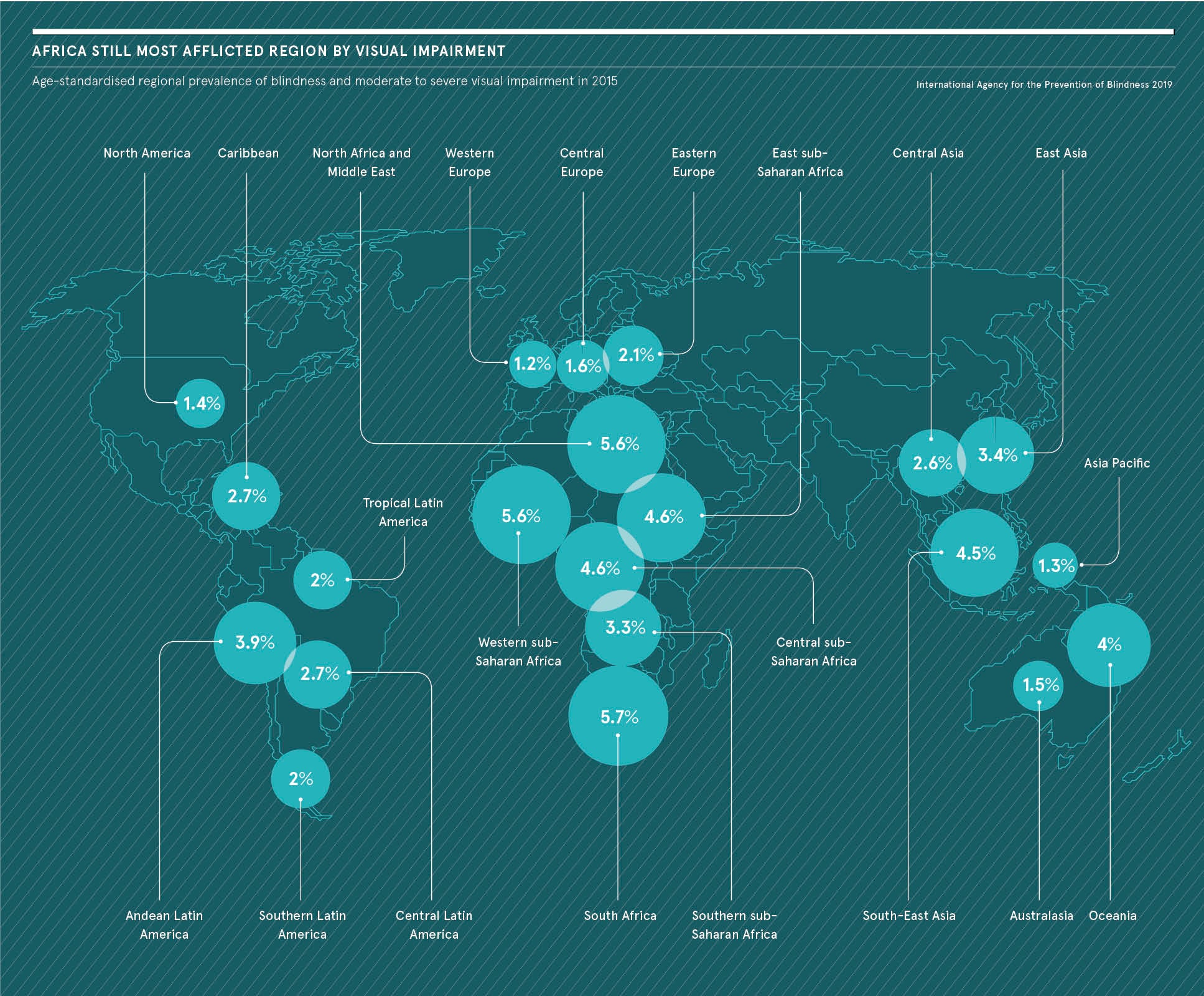

But like a 3D game of constantly moving shapes, the landscape for eye problems has been rapidly evolving and it’s therefore challenging to plot progress. Demographic changes, including population growth and ageing alongside the rise of non-communicable diseases, have led to a greater prevalence in eye diseases. At the same time, reaching the so far unreachable and identifying those neglected and remote populations remains an issue.

“We know the prevalence of vision impairment, adjusting for age, has consistently declined in every region of the world in the past 25 years, with the biggest gains in low-income countries. An estimated 90 million people around the world have been treated or prevented from vision loss since 1990,” says Mr Holland.

There are also other milestones. River blindness is on track to be the first blinding disease to be eradicated globally. Also known as onchocerciasis, it was virtually eliminated in the Americas by 2015 and in 2016 there were almost 150 million treatments in Africa.

Meanwhile, the number of people at risk of trachoma, an infectious bacterial eye disease, has fallen from 1.5 billion in 2002 to 142 million in 2019, an astonishing reduction of 91 per cent, according to WHO data. A mind-boggling 450 million doses of antibiotic have been distributed so far and WHO has declared trachoma has been eliminated from eight countries.

“Progress made in the elimination of blinding neglected tropical diseases, namely onchocerciasis and trachoma, are probably the most striking success stories of Vision 2020,” says Professor Serge Resnikoff, immediate past chair of the International Coalition for Trachoma Control.

Blindness rates set to triple by 2050

Cataracts, the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment globally and accounting for a quarter of all cases, has been a key focus for Vision 2020. As a result, many low and middle-income countries have seen substantial rises in cataract surgeries over time. For instance, India has successfully increased its rate by nearly nine-fold in three decades.

Cataracts, the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment globally and accounting for a quarter of all cases, has been a key focus for Vision 2020. As a result, many low and middle-income countries have seen substantial rises in cataract surgeries over time. For instance, India has successfully increased its rate by nearly nine-fold in three decades.

If it looks like a winning battle, think again. Despite gargantuan global efforts, the number of people with visual impairment is marching northwards, as we all live longer. “The number of people who are blind will triple by 2050,” says Ian Wishart, chief executive of the Fred Hollows Foundation.

Drill down and the numbers speak for themselves. By 2030, globally we will have more than a billion people in old age and already this cohort accounts for half of those with eye problems, the IAPB says. By 2050, it is estimated there will be almost five billion myopic, or short-sighted, people; that’s half the predicted global population, so clearly access to eye tests and glasses is still not universal.

“There are other issues too. By 2040, 70 million people will have diabetic retinopathy also known as diabetic eye disease. We need to act now if we are going to reverse these trends,” warns Mr Holland.

Road to universal eye health is rocky

The challenges are immense; most health systems in poorer countries are chronically under-funded. This is where 90 per cent of the world’s visually impaired people live. The global cost of lost productivity due to uncorrected poor vision is also a staggering $272 billion a year, according to WHO. It reduces people’s ability to learn and in severe cases can be debilitating. But visual impairment doesn’t grab headlines, because it doesn’t kill people; it isn’t malaria or ebola.

“Eye health is not seen as a priority by governments, so while political effort at WHO level has been strong, it’s difficult to make the case at national level where resources are scarce,” says Juliet Milgate, director of global policy and advocacy at Sightsavers.

Worryingly, gender inequity in eye health is a burning issue. Women are still 1.3 times more likely to be blind than men, according to the IAPB, meaning 55 per cent of the visually impaired are women. Less access to transport, decreased social mobility, poor health literacy and less financial freedom are some of the reasons. “The fact is, in some places more health importance is given to men and boys,” says Professor Shahina Pardhan, director of the Vision and Eye Research Unit at Anglia Ruskin University.

Despite these challenges, this is an exciting time to be tackling eye health, since the toolkit and capabilities have expanded; some are even calling it a pivotal moment. “We’ve reached a point where, for the first time in history, we could eliminate avoidable blindness and visual impairment,” says Dr Andrew Bastawrous, chief executive of Peek Vision and associate professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

“This isn’t just an abstract proposition; the treatments and infrastructure needed to address most of the world’s avoidable issues are cost effective, proven and ready to be deployed.”

Universal eye health becoming a priority at last

It helps that universal health coverage is also topping the global agenda and at the same time there’s greater recognition eye health is key to realising many United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

“We now have adequate basic data, a degree of political will and a catalogue of demonstrable success upon which we can build,” explains Ronnie Graham, trustee at Vision Aid Overseas. “Technology, both to reach more people and reduce costs of diagnosis and surgery, can also transform the sector.”

For instance, Google is developing an artificial intelligence tool to detect diabetic eye disease. Other companies, such as Forus Health in India, are designing low-cost equipment to eradicate preventable blindness. While Arclight is an inexpensive, easy-to-use, pocket-sized ophthalmoscope for diagnosing diseases in the developing world, costing as little as £5. Peek Vision is also deploying smartphones to enable eye checks. Portability is key, since remote regions suffer more from poor eyecare.

“Often the nearest optician is 50 kilometres or even farther away from some communities, so there is a problem of access,” says Kristan Gross, global executive director of the Vision Impact Institute. “The other issue is affordability, as solutions have historically been seen as a high-cost option.”

Why business leaders must prioritise eyecare

This is not just a public health and government agenda, there are also calls on the global business community to play a roll. By tackling short-sightedness, or myopia, alongside blindness and other critical eye diseases raises the profile and clarion call for universal eyecare.

“We carried out research on productivity at a tea plantation in Assam, India. By simply providing pairs of affordable glasses, the plantation saw a 22 per cent increase in productivity, the largest productivity increase of any health intervention,” says James Chen, founder and chief executive of Clearly.

“Putting free eyecare at the top of a business agenda makes sense, not just as a corporate social responsibility initiative, but also economically and for the future of any business growth.”

The next 20 years will be a crucial period. Priorities will have to be made. Training more eyecare workers in places such as Africa and South America will be vital.

“In fact, each region has its own set of priorities, based on the prevalence of eye conditions and socio-demographic factors. There is no one size fits all,” Mr Holland concludes. “Broadly, however, there is the challenge of getting the world to engage with eye health.”

Success stories from around the world

1 Ending trachoma in Ethiopia

Hawiti Tufa, a 60-year-old grandmother, living four hours south east of Addis Ababa in rural Ethiopia, has been unable to help her family for a year because of the agony caused by trachoma, the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness. It all changed after visiting a makeshift surgery. “I have better vision now and the pain is reduced,” she says.

In Ethiopia, 72 million people live where this preventable disease is endemic. “Two years ago, we conducted the largest trachoma elimination project in the world here, supporting one in five surgeries and one in five doses of antibiotics globally,” explains Ian Wishart, chief executive of the Fred Hollows Foundation.

Trachoma elimination is a major success story. Charting via the Global Trachoma Mapping Project has been the single largest infectious disease mapping project in the world, leading to increased screening and treatment with infection rates dropping by 91 per cent.

“Moreover, the number of people requiring surgery for trachomatous trichiasis, the late blinding stage of trachoma, has reduced from 7.6 million people in 2002 to 2.5 million in 2019,” says Professor Serge Resnikoff, immediate past chair of the International Coalition for Trachoma Control.

2 Battling cataracts in Pakistan

Mihi Bali stopped work as a cotton picker in Sindh, Pakistan, when her vision started to cloud because of cataracts, yet she could not afford to visit an eye doctor. A health worker eventually made a diagnosis and had her treated at a hospital. “I’m happy now that I will start working as an agricultural worker to increase my family’s income,” explains Ms Bali.

Over half a million people have cataracts in Pakistan; it’s the most common cause of avoidable blindness in the country. Scale this up and an estimated 18 million globally have cataracts. “Yet it can now be treated with surgery at remarkably low cost,” says Juliet Milgate, director of global policy and advocacy at Sightsavers.

Cataract surgical rates are now on the increase in many countries and the disease is included in most national plans for the prevention of blindness. “We are plateauing now in terms of cataract visual impairment,” says Ronnie Graham, trustee at Vision Aid Overseas. Data from WHO shows there’s a 25 per cent decrease in blindness prevalence in India and this could be due to increased cataract surgeries.

3 Tackling river blindness in Uganda

Okello Charles works as a volunteer in northern Uganda, distributing the antibiotic Mectizan, used to treat river blindness. The 35 year old volunteered as fly catcher on the Aruu River, near his village Lapaya, which is a breeding ground for the tiny black flies that spread the disease.

“I feel happy I can do something to protect my children,” he says. “I have many friends and relatives who have gone blind. That is what encouraged me to be part of the team that catches flies.”

Sightsavers has been busy over the last three years delivering 60 million treatments to stop infection from spreading and reaching 9.5 million people with onchocerciasis, not just in Uganda, but in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea-Bissau and Nigeria.

“The progress made to date is significant and demonstrable,” says Juliet Milgate of Sightsavers. “On neglected tropical diseases such as onchocerciasis, it is essential that we continue to support existing efforts and don’t take our eye off the ball.” Globally, more than 300,000 people are blind because of river blindness. But the disease is being eliminated in some countries.

Setting sights on universal eye health in 2020

How to tackle eye disease globally

Blindness rates set to triple by 2050