Anti-ageing is a curious misnomer. By dint of our very existence, we are all ageing, regardless of whether we are 18 or 60. And yet this natural process has incited a highly profitable, anxiety-inducing crusade from the beauty industry.

The countless time-defying creams, Botox injections, laser treatments and bio-identical hormones on the market all speak to one unconscious belief that if beauty is synonymous with youth, then the very act of ageing is to become ugly, to relinquish our desirability and, to a certain extent, our sexuality.

Both polarities are, of course, an absolute fallacy. To say it out loud, or to put it in print, only underlines the inherent absurdity of our fetishistic thinking around youth and our ageist culture.

“As a society, I think European women used to be quite good about ageing,” says Sue Harmsworth, the founder of ESPA who, at 72, exemplifies graceful ageing. “We wanted to keep the character in our face.”

But along came America with Hollywood productions that featured 25 year olds playing 45 year olds and things went pear shaped. In stark contrast to, say, Greek or Native American cultures where elders are celebrated, most Westerners have come to view ageing as an illness in want of correction, an affliction that demands an intensive skincare regime so we can walk around looking like a vague facsimile of our former self. But, thanks to wellbeing pioneers like Ms Harmsworth, the way we age may be about to change.

Ageing well

The great irony is that advances in medical science and technology are allowing us to live longer. There are currently more than 800 million people over 60 in the world, an upward trajectory that shows no sign of slowing down and that will inevitably force us to embrace, rather than fear, the idea of ageing. The difference is we have to learn to age well.

For now, though, gerontophobia is rife and anti-ageing remains the most lucrative sector in the beauty business. The UK anti-ageing facial care market was worth £465 million in 2015, up from £459 million in 2014, according to market researchers at Mintel. The claims can be recited on command by any baby boomer with a mirror: “banish dark circles”, “reduce the appearance of fine lines”, “erase wrinkles”.

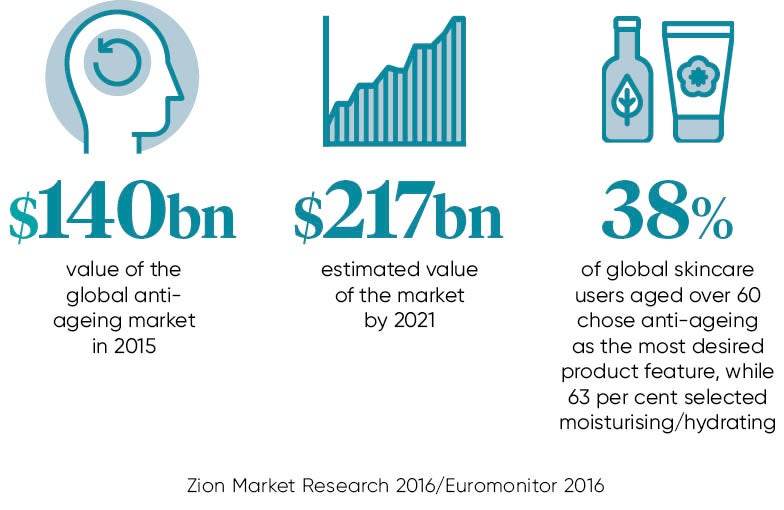

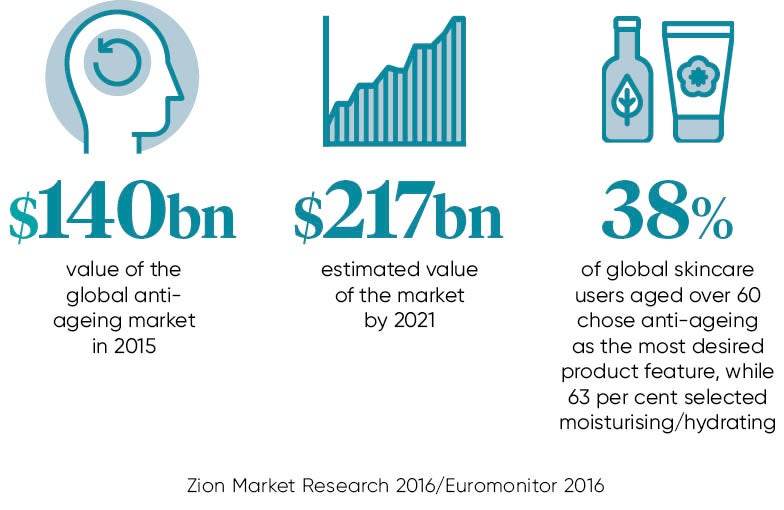

Reports published by Zion Market Research valued the global anti-ageing market, which includes cosmetic procedures along with facial skincare, at $140.3 billion in 2015. They expect the value to rise to $216.52 billion by 2021; impressive figures for services that prey on insecurity rather than any sound medical data.

As skeptics are only too keen to tell you, there is a limited amount a cream or procedure, even an invasive one, can do to stall the passage of time in any permanent fashion. If we have excelled at anything, it’s marketing the idea of anti-ageing rather than harnessing it though any kind of reliable technology. It is for this reason that most manufacturers continue to hide their “proprietary age-fighting formulas” with patents that protect trade secrets.

Chronological age can’t be changed, but our biological age can certainly be influenced

Rigorous testing is not a top priority for brands, many that employ legally vague terms like “clinically proven” or “dermatologist approved” on the label. The harm of bombastic marketing isn’t that it’s misleading, it exonerates the consumer from taking responsibility for other factors which contribute to ageing, such as diet, exercise and lifestyle.

It’s worth noting that many of the big spenders in the anti-ageing category are under 35, a hard-living contingent that, for all intents and purposes, are not yet subject to the visible signs of ageing. The endless visits to dermatologists and cosmetic doctors are made passable under the awkward label of prejuvenation and procedures, such as microdermabrasion or Botox, are happily administered before anything starts to sag or wrinkle.

It is an aggressive tactic against an invisible enemy, one that will no doubt have repercussions in later years. While preventative measures should be advocated, turning to procedures that aggressively disrupt the physiology of the skin is, perhaps, going a step too far.

Slow ageing

In 2017, a new message is coming to the fore. Ms Harmsworth calls it “slow ageing” or, in layman’s terms, “taking care of your skin through every decade of your life rather than wrestling it into any kind of subjugation”. It is through this progressive nurturing, via skincare, diet, exercise and, she insists, positive mental attitude, that ageing becomes manageable. Empowering, even.

Her simple wisdom bears out in her appearance. Ms Harmsworth looks 20 years younger than her 72, a difference that was validated by a test that measures chronological age against biological age. Tests like the one by GlycanAge calculate the amount of sugar molecules (glycans) in the blood to derive a biological age for the subject.

“Chronological age can’t be changed, but our biological age can certainly be influenced,” she says. “I don’t like talking about skin in chronological terms. There are 55 year olds who have the skin of a 75 year old and vice versa.” She is hinting at epigenetics, a growing field of research that demonstrates how gene expression, and thus ageing, can be influenced by variables including lifestyle choices, emotional wellbeing, psychological health and what we now broadly call “wellness”.

“I don’ think of myself as 72 at all. I don’t talk like I’m 72 or move like I’m 72. We’ve spent the last ten years worrying about our bodies, I think the next ten years will be about our mental health,” Ms Harmsworth concludes, as if to emphasise the old cliché that age is little more than a state of mind.