Sir Simon Stevens, NHS England chief executive, described obesity as “the new smoking” when calculations forecast 360,000 people will have weight-related cancers by 2030, a rise of 62 per cent.

Diet and exercise alone will not resolve the multi-billion-pound obesity epidemic. Bariatric surgery, which reduces stomach size, is the most effective treatment. It has even been acclaimed as the most effective intervention in healthcare, but only 0.1 per cent of eligible UK patients opt for it, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). This has created a huge, unmet need for weight-loss drugs.

An effective, safe, cheap, anti-obesity pill could become one of the biggest-ever pharma blockbusters. In 2014-15 obesity cost the NHS £6.1 billion. The bill is projected to reach £9.7 billion a year by 2050, with overall costs to society of nearly £50 billion annually.

But the multi-billion-dollar game of pharmaceutical roulette generates many more losers than winners. The history of weight-loss drugs is littered by disaster and drugs taken off the market amid safety concerns, from heart attacks to depression and suicide.

Only two years after being acclaimed the holy grail of obesity drugs, lorcaserin was withdrawn this year. Other weight-loss drugs had been found to increase the risk of heart attack, which is a threat to obese patients even before they take any drugs. A US trial of 12,000 patients concluded lorcaserin patients were not similarly at risk, but they were judged to be at increased risk from cancer.

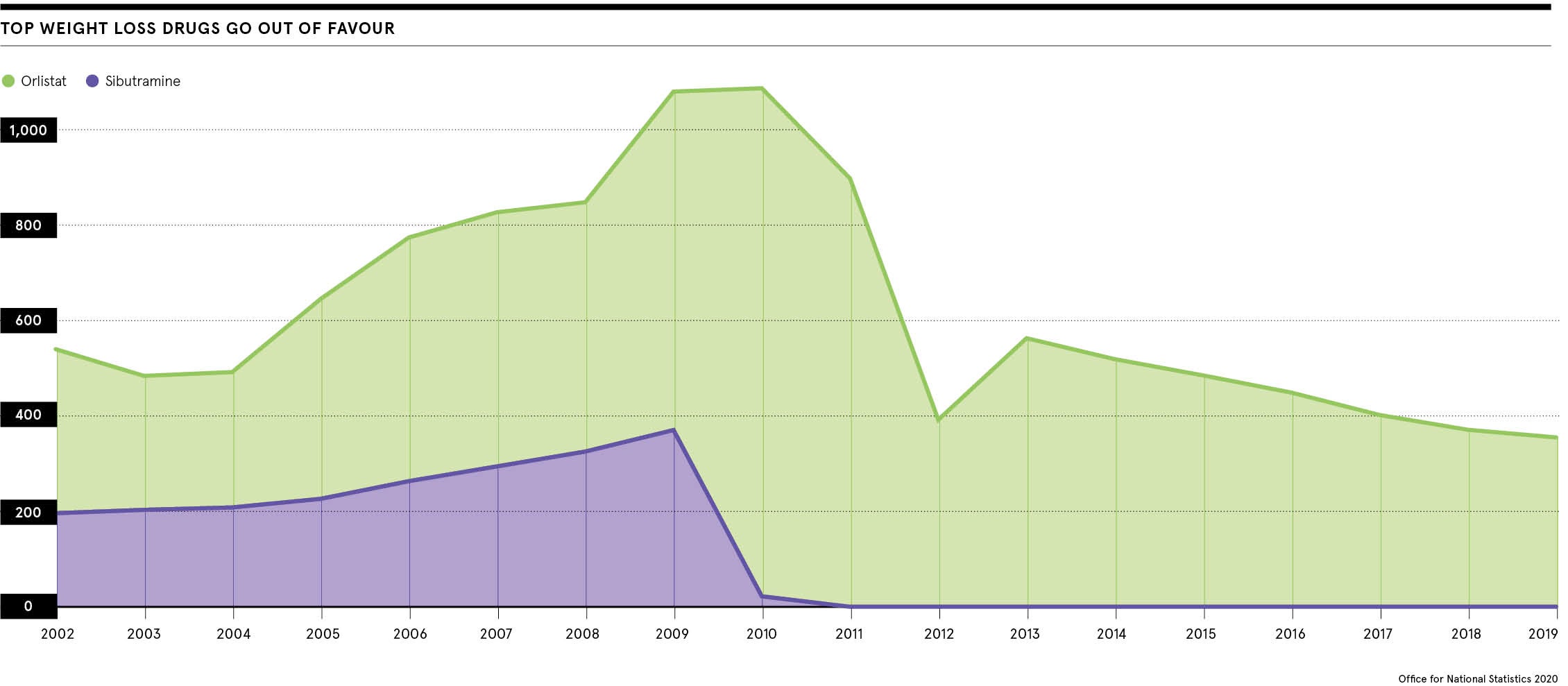

Irrespective of cancer fears, the chances of lorcaserin being licensed for the NHS were limited by costs ranging from £1,860 to £2,700 per patient a year. Other notable drugs taken off the market included rimonabant in 2008 and sibutramine two years later.

Sibutramine worked by boosting levels of norepinepherine and serotonin, two chemical messengers in the brain, and inducing feelings of fullness after eating. But the European Medicines Agency suspended all its European licenses, ruling that potential side-effects, including stroke and heart attack, outstripped any benefits.

Weight-loss drugs only a quarter as effective as surgery

This left the NHS with only one officially approved weight-loss drug. Sold under the band name Xenical, orlistat helps to avoid weight gain and produces weight loss, but it is only about a quarter as effective as bariatric surgery. It prevents absorption of a third of fat in food. Undigested fat is excreted. Many patients struggle to tolerate orlistat’s unpleasant side-effects which include diarrhoea.

A major plus of orlistat is cost at about £18 a month. In contrast, the so called list price of the gentler liraglutide is £196.20 a month or more than £2,350 a year. Liraglutide mimics a natural hormone, glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1), that helps to regulate hunger.

Last week, NICE recommended making liraglutide available on the NHS after a confidential discount had been agreed with manufacturers Novo Nordisk.

But the new licence is restricted to only about 3,000 patients who are at high risk of cardiovascular disease, have pre-diabetes and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35kg. A person’s BMI is their weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in metres. Normal BMI ranges from 18.5 to 24.9kg.

Another form of liraglutide, with the brand name Victoza, has a lower dose and is approved to treat diabetes, but not obesity alone.

We cannot treat a quarter of the population with liraglutide

Why has NICE limited liraglutide prescribing? Its unenviable job is to balance infinite demand with finite, scarce resources. In 2018 the Nuffield Trust reported that 28 per cent of the UK population was obese. As Professor John Wilding, of the University of Liverpool and president of the World Obesity Federation, says: “We cannot treat a quarter of the population with liraglutide.”

Bariatric surgery: the key to new drugs

The picture might sound gloomy, but bariatric surgery is playing an unforeseen role in filling the therapeutic vacuum.

Wilding explains: “Bariatric surgery has given us new insights into the physiology of the gut. We now know that by altering the anatomy of the gut and altering the way gut hormones work, we can overcome the problems people have when they diet.

“The big problem with a diet is that however hard you try, your body is going to fight you, by making you feel hungrier and slowing your metabolic rate. This is why it is so hard to lose weight and why people inevitably lose the battle.”

It is also why Wilding insists obesity should be treated as a disease. He challenges the popular idea that obesity reflects personal irresponsibility rather than policies pursued by the food industry to promote cheap, high-fat, high-sugar food with super-sizing, meal deals and buy-one, get-one-free offers. Last month more than 800 food and drink manufacturers signed a letter attacking government proposals to ban online advertising for products high in salt, sugar and fat.

“The ‘personal responsibility’ argument is incorrect as it fails to recognise the powerful genetic and environmental pressures that cause obesity in the first place,” says Wilding.

“If you told people with asthma they needed to work harder at breathing, or those with depression to pull themselves together, it would be considered inappropriate. This is what those advocating that obese people should eat less and move more are doing. It’s far more complicated than that.”

The ‘personal responsibility’ argument is incorrect as it fails to recognise the powerful genetic and environmental pressures that cause obesity in the first place

Research arising from bariatric surgery is highlighting this complexity. Much of it is focused on so-called incretin hormones, including GLP-1, the hormone liraglutin so effectively mimics. Stimulating a decrease in blood glucose levels, incretins are released after eating and enhance secretion of insulin, helping glucose enter the body’s cells.

Tomorrow’s prescription medications

Even though liraglutide has just been licensed by NICE as an obesity treatment, its days may be numbered. It has been surpassed by semaglutide, a once-weekly injection used to treat type-2 diabetes.

Wilding says: “Semaglutide is cheaper than liraglutide even though it is made by the same company. It is not approved for treating obesity, but it has been tested as an obesity treatment. The average weight loss in the one-year trial was 16.9kg, which is more than double what we’ve seen with liraglutide. It may become available to treat obesity in the next 18 months.”

In future, powerful combination therapies could match bariatric surgery. These include tirzepatide which targets GLP-1 and another hormone, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), released by the small intestine to control digestion.

The Lancet medical journal reported in 2018 that patients taking tirzepatide lost significantly more weight than those taking just a GLP-1 drug alone. But it will take several years for tirzepatide to reach the market, if it is licensed. Clinical trials are due to end in 2024.

There is even the prospect of a triple-action therapy that could outmatch bariatric surgery, targeting GLP-1, GIP and glucagon, a hormone controlling blood sugar: this really could be the holy grail of weight-loss drugs.

There could be another major benefit to this holy grail. It could help to kill the booming market in unlicensed, dangerous and fake diet pills. The Pharmaceutical Journal recently reported that a pill known as DNP had killed a 21-year-old student. Widely available on the internet from sites which seem to be legitimate, DNP was first used on an industrial scale to make bombs. Almost certainly the student never knew that.

Sir Simon Stevens, NHS England chief executive, described obesity as “the new smoking” when calculations forecast 360,000 people will have weight-related cancers by 2030, a rise of 62 per cent.

Diet and exercise alone will not resolve the multi-billion-pound obesity epidemic. Bariatric surgery, which reduces stomach size, is the most effective treatment. It has even been acclaimed as the most effective intervention in healthcare, but only 0.1 per cent of eligible UK patients opt for it, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). This has created a huge, unmet need for weight-loss drugs.

An effective, safe, cheap, anti-obesity pill could become one of the biggest-ever pharma blockbusters. In 2014-15 obesity cost the NHS £6.1 billion. The bill is projected to reach £9.7 billion a year by 2050, with overall costs to society of nearly £50 billion annually.