If all humanity was wiped out tomorrow and we had to reconstruct mankind from genetic data and health research found on computers across the globe, our avatar would look mostly white and Caucasian. You would be hard pushed to rebuild Asian and African populations with their resplendent genetic variety. This has huge implications for our health, globally.

Transferring findings from one population to another is a major problem

In an age when the burning injustices of diversity and inclusion are being codified into law, society and in businesses worldwide, it is only now being fully realised in genetics and medical studies.

“The lack of diversity may be one of the biggest challenges that we face in the potential advancement in health research,” explains Dara Richardson-Heron, chief engagement officer at the All of Us Research Program in the United States.

Genome sequencing makes equality even more important

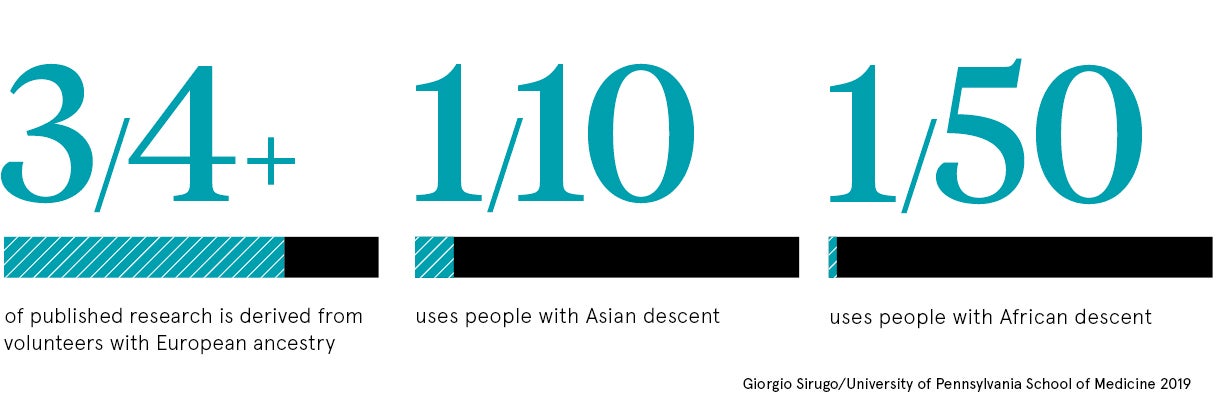

Genome-wide association studies show that more than three quarters of published health research is derived from volunteers with European ancestry, whereas Asians represent 10 per cent and Africans 2 per cent. In mental health, 96 per cent of people studied are from Westernised, educated, industrial and rich democracies. While minorities are currently poorly represented in the UK Biobank, which aims to genotype 500,000 people. So the big picture is hardly one of inclusion.

The problem of healthcare inequalities also existed before we sequenced the human genome, but as our knowledge of genetics and links to disease increases, promising new tailored treatments, the lack of diversity matters more.

“This a major issue and one that researchers and funders must address. We’re starting to see changes, but many challenges remain,” says Mary De Silva, head of population health at Wellcome.

Diversity matters in medical research and clinical trials because diseases vary greatly depending on the community you study. “In complex problems such as Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and multiple sclerosis, we know that manifestations vary across populations,” says Giorgio Sirugo, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. “Transferring findings from one population to another is a major problem.”

Different patient populations will respond to different treatments

For instance, South Asians have higher levels of heart disease and diabetes, while South Americans have more asthma and a poor response to certain inhalers. “The common criticism is that research findings found by using white individuals will benefit mostly white individuals,” says Doug Speed, assistant professor at the Aarhus Institute of Advanced Studies in Denmark.

Doctors may also diagnose conditions or prescribe medicine that will work for those with European genes, but for other racial backgrounds, it can be less effective. “In my opinion, all medicine is impacted when there’s no diversity in the system,” says Emmanuel Peprah, assistant professor at New York University College of Global Public Health.

“Medical studies start from basic discoveries to research, which then focuses on how to bring to scale, at a population level, evidence-based discovery. In each of those significant steps, if populations of diverse background are omitted, the implications for the findings and those that could potentially benefit from the health research decreases.”

Strides being made towards ethnic diversity in health

All areas, from medicine to surgery, from diagnoses to treatments, from drug discovery to organ transplantation, could be impacted. The good thing is the medical profession is now working hard to redress this imbalance.

“We are aware of the dangers of extrapolating from health research in Western populations. We are also very much aware of the importance of understanding the influence of ethnic diversity on health,” says Dr Joe McNamara, head of population health at the Medical Research Council.

A number of projects have been funded. There’s the Human Heredity and Health in Africa initiative, the All of Us Research Program in America, which will gather data from more than a million people including minorities, the Born in Bradford birth cohort, with a high representation of people of South-Asian origin, and the China Kadoorie Biobank, made up of data from 500,000 people across China.

“However, the structures and incentives in the research ecosystem make this work the exception rather than the rule,” says Ms De Silva. “A concerted effort by funders, including national governments, is needed to change the incentive structure, and to fund and value health research in more diverse populations.”

Trust is crucial for getting people to sign up for studies

Professor David van Heel, who leads the East London Genes & Health project, is recruiting 100,000 British-Bangladeshis and British-Pakistanis with the aim of linking genes with health records. He realises recruitment is a big issue.

“Trust is so important,” he says. “Different communities react to different enrolment techniques. Face-to-face recruitment in a trusted setting works for South-Asian people here in east London; via post, smartphone or online recruitment doesn’t work. People are also willing to get involved if they’ve experienced ill health among family or friends.”

Some groups have been sceptical or hesitant to participate in health research. Studies have been described as exploitative or unethical, while results and discoveries haven’t been shared with those who took part.

“It’s important that individuals know how they may benefit when they choose to participate in research,” says Dr Richardson-Heron. “We’re offering an opportunity for under-represented communities to have a seat at the table, from the start, in building a health research programme that may have a significant impact on the health of their communities and for future generations.”

Yet there’s still a defence for homogeneity in genetic studies. “It can be more efficient and a better way to spend money focusing on one ethnic group. A study of 10,000 individuals from one population will likely be more successful than a study of 20,000 individuals from 20 populations,” explains Dr Speed. “The problem is the majority of studies are all white and very few non-white.” The promising thing is that diversity is now a buzzword in the healthcare community too.

Genome sequencing makes equality even more important

Different patient populations will respond to different treatments