The pressure is on for businesses to take ethnicity pay gap reporting seriously.

“Diversity and pay equality is a rising-tide risk,” says Ken Charman, chief executive of uFlexReward. “We’re already seeing an increase in pay-related discrimination claims. Organisations with ethnicity pay gaps will need to be prepared for queries from employees as numbers start to be disclosed.”

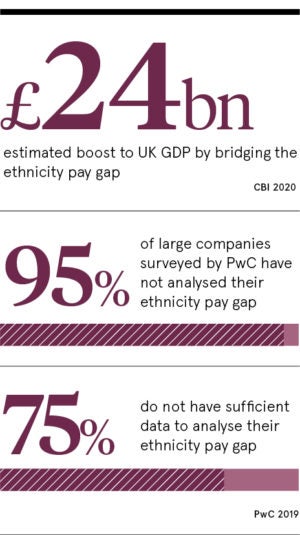

According to the CBI, UK GDP could be boosted by £24 billion a year by simply bridging the ethnicity pay gap, and those organisations with the most ethnically and culturally diverse executive teams are 33 per cent more likely to outperform their peers on profitability.

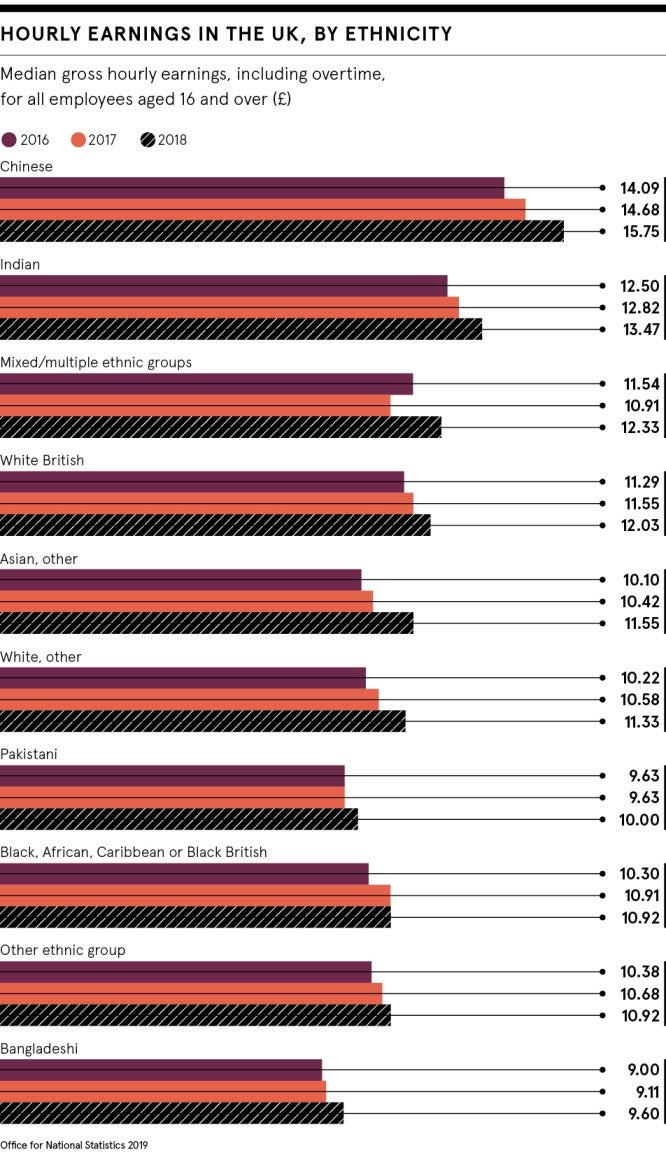

However, 2019 government figures show the overall picture on race discrimination and pay is a complex one. Some 77 per cent of white people were in employment last year, compared with 65 per cent of people from all other ethnic groups combined, but wages vary among all ethnic groups.

Data-driven ethnicity pay gap reporting is essential in understanding the different experiences of individual ethnic groups beyond anecdotal data. Indeed, employees from the Chinese ethnic group earned 31 per cent more than white British workers in 2018, according to the Office for National Statistics, while those from Bangladeshi backgrounds earned 20 per cent less than white employees.

The challenges of collecting data

Voluntary reporting is still in its infancy, so changing the status quo will take time. “Only a minority of businesses have actually volunteered to report this information so far,” says Boma Adoki, associate at commercial law firm Stevens & Bolton. “The available data is therefore limited and so any conclusions whether the sands are shifting when it comes to equal pay among ethnicities would be premature.”

Voluntary reporting is still in its infancy, so changing the status quo will take time. “Only a minority of businesses have actually volunteered to report this information so far,” says Boma Adoki, associate at commercial law firm Stevens & Bolton. “The available data is therefore limited and so any conclusions whether the sands are shifting when it comes to equal pay among ethnicities would be premature.”

Since late-2018, just under 250 companies have made their commitment to ethnicity pay gap reporting clear, by signing up to the Business In The Community Race at Work Charter. “They have 233 signatories,” says Ruth Thomas, co-founder and principal consultant at CURO Compensation. “It is still a very small number of employers and, according to a PwC survey last year, involving 80 significant UK employers, 95 per cent of them weren’t doing anything; 75 per cent of them didn’t have the data to do anything.”

Coming up with the data can seem like a huge undertaking for a small business. “Many firms put off ethnicity pay gap reporting due to the anticipated complexities of collecting data, and the concerns around the quality and extent of this data,” says Charman, whose company uFlexReward is funded by Unilever and helped develop the system designed to provide pay equity data to Unilever’s remuneration committee. “Every company has the data. What they mean is they face technical problems providing it.”

Formulating action plans for change

The challenges in accessing and analysing the numbers calls for extra resources, which larger companies are more likely to have. “The likes of Bupa, ITN and Citigroup, as well as each of the big four accountancy firms, have committed to reporting. Hopefully these big players will lead by example,” says Adoki. “We must publish, and in turn analyse, the numbers to be able to fully understand where the issues lie.”

The good news is that the more companies of all sizes that commit to ethnicity pay gap reporting, the better our understanding of the action plans needed. “It is currently difficult to draw year-on-year comparisons due to varying disclosure rates of available data,” adds Adoki. “In time, we need more and more businesses to participate with reporting and therefore increase the availability of data. It should then be possible to determine whether the reporting system is actually enacting change.”

Charman points to technological solutions to help with data collection. He says: “A lite version of the reporting software developed by uFlexReward is now available for organisations to easily collate the necessary data for reporting from an anonymised employee demographics file extracted from their human resources information system.”

Thomas at CURO Compensation adds: “There are some actions that can have a relatively fast turnaround, particularly in recruitment. Blind CVs in terms of name and educational establishment, balanced shortlists and recruitment panels make for impact you can see in a short time.”

The Mayor of London’s Greater London Authority Ethnicity Pay Gap Action Plan, published in January 2019, suggests establishment of a black, Asian and minority ethnic staff network, unconscious bias training, and directorate-level diversity and inclusion action plans.

Paving the way for mandatory reporting

The multiplicity of action plan items reflects the complexity of factors that lead to the ethnicity pay gap and the necessity of tackling them. As Adoki says: “From a commercial perspective, publishing the numbers also speaks to the transparency of a business. For employees, job seekers, shareholders, and customers and clients alike, transparency is a key concern. By publishing the numbers, businesses can indicate they are open to scrutiny on their structures and potential barriers to opportunity.”

Charman agrees: “There is no value in putting off ethnicity pay gap reporting. Starting now with the necessary planning and access to data could reduce the risk of regulatory or legal implications further down the line. Ethnicity pay reporting and any further future reporting requirements are fundamental steps in the journey to improve workplace equality.”

After the gender pay gap and the ethnicity pay gap, companies will be forced to scrutinise the treatment of other marginalised demographics. To pave the way for the most positive outcomes, for employees and organisations alike, it’s surely best to get used to ethnicity pay gap reporting now, ahead of it becoming mandatory.

The challenges of collecting data

Formulating action plans for change