The argument FOR a four-day week

The prospect of a three-day weekend is music to the ears of most employees.

Shortening the working week to four days is championed by the Trades Union Congress. In an ambitious report, the TUC argues for productivity gains from technology to be shared with workers, and sets out steps that would lead to shorter hours and higher pay.

“I believe that in this century, we can win a four-day working week, with decent pay for everyone,” says TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady.

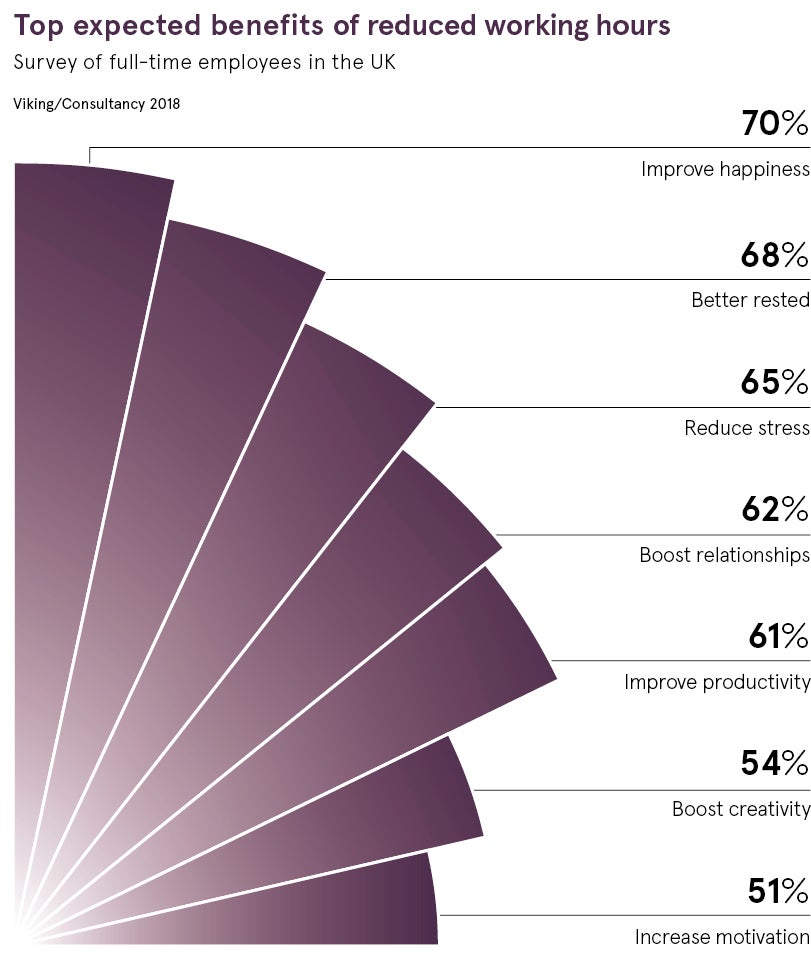

When it comes to employees, the appeal is clear. Less time in the office means more time to spend with family and on maintaining a healthier work-life balance. Employers are now also seeing value in working less, as a growing body of research suggests a four-day week is good for business.

A recent experiment in New Zealand, at a wealth management firm, trialled a four-day week over a two-month period. Some 54 per cent of staff felt they could effectively balance their work and home commitments, while after the trial this number jumped to 78 per cent.

“Recent evidence has shown that a four-day week can reduce employee levels of stress, enable them to be more absorbed at work and make more efficient use of their work time,” says Shainaz Firfiray, associate professor of organisation and human resource management at Warwick Business School.

Is the four-day week the answer to presenteeism?

Dr Daniel King, professor of organisation studies at Nottingham Business School, agrees. “Some of the experiments that have taken place so far indicate that by only working four days employees can have the same level of productivity as they are more focused and make better choices about what they work on,” he says.

A four-day working week might be the solution to presenteeism. “Without structured initiatives to ensure the proper work-life balance is adopted by staff, there is a real danger that this can lead to sluggish productivity and impact the quality of work as staff come under undue pressure to deliver,” says Peter Clark, co-founder of Qlearsite, a human resources analytics company.

The ripple effect of this is an improvement in recruitment. “British workers value work-life balance over any other aspect of a job,” says Martin Talbot, group marketing director at Total Jobs. “Offering a shorter week could well be the difference in securing the best talent.”

Some UK companies have already shifted to a four-day week. Gloucester-based public relations agency Radioactive recently introduced the model without cutting pay after a successful trial run. Rich Leigh, the agency’s founder, says: “I’ve never wanted a single member of the team to be flat-out, instead opting to give people enough time and space to be at their best.”

The argument AGAINST a four-day week

Working four days a week sounds like a dream job, but in reality it’s just wishful thinking.

While reducing working time might be a popular idea among employees, the reality of implementing it without a detrimental impact on productivity remains an unknown. Experts worry that shortening the working week will result in compressing existing hours into fewer days, so a four-day week could mean a ten-hour day.

“Trying to squeeze a full standard working week into four days could negatively impact morale and productivity,” says James Lloyd-Townshend, chief executive of Frank Recruitment Group, adding that even if a week did reduce from 40 hours to 32, this wouldn’t necessarily have a positive impact.

“If people know they have less time to get work done, this could mean they cut out procrastination and really focus on the work in front of them. However, it’s just as likely that this could leave people stressed out and time pressured.”

Experts have raised concerns that a four-day week is being held up as a trendy solution without sufficient data to back it up. The New Zealand experiment by a wealth management firm attracted a lot of buzz around the idea, but while it found quality of the work didn’t dip, it also concluded that it didn’t improve either.

Four-day week less desirable than true flexibility

Overlooked in the debate is the need to acknowledge a significant shift in work-life preferences among a modern and highly skilled workforce. “A four-day week proposal is a regimented approach that goes against the grain of what the majority of employees are really seeking, which is true flexibility,” says chief executive and co-founder of Worksome, Morten Petersen.

Instead of a four-day week, some experts are calling for flexible working time. “One of the dangers of focusing on the number of days per week is that it doesn’t focus on the number of hours people are working,” says Stuart Hearn, chief executive of Clear Review. “We need to think about the nuances of what we’re trying to achieve; it might be optimising hours per week, rather than optimising days.”

Fuze, a business communications company, carried out research into this idea and found that having set working hours, whether over four or five days, is not an effective business model. When asked to select their preferred working hours, 39 per cent of workers said they would choose to start work at 7am, as they believed an earlier start would improve their productivity. The research also found that nine out of ten workers want a job that offers flexitime.

“Instead of enforcing yet more restrictions, businesses should allow staff to work when they are most effective,” says Bradlee Allen, product evangelist at Fuze. “True flexibility will not only increase productivity, but it will also make workers feel engaged, motivated and valued.”

The argument FOR a four-day week

Is the four-day week the answer to presenteeism?