Be honest. How many times have you checked your phone, sent texts, hit social media, instant messaged your friends and generally browsed online – all while you’re supposed to be at work? According to research by Direct Line, you could be in for a shock. It found the average person in the UK checks their mobile device a staggering 253 times a day – every four minutes of their waking day.

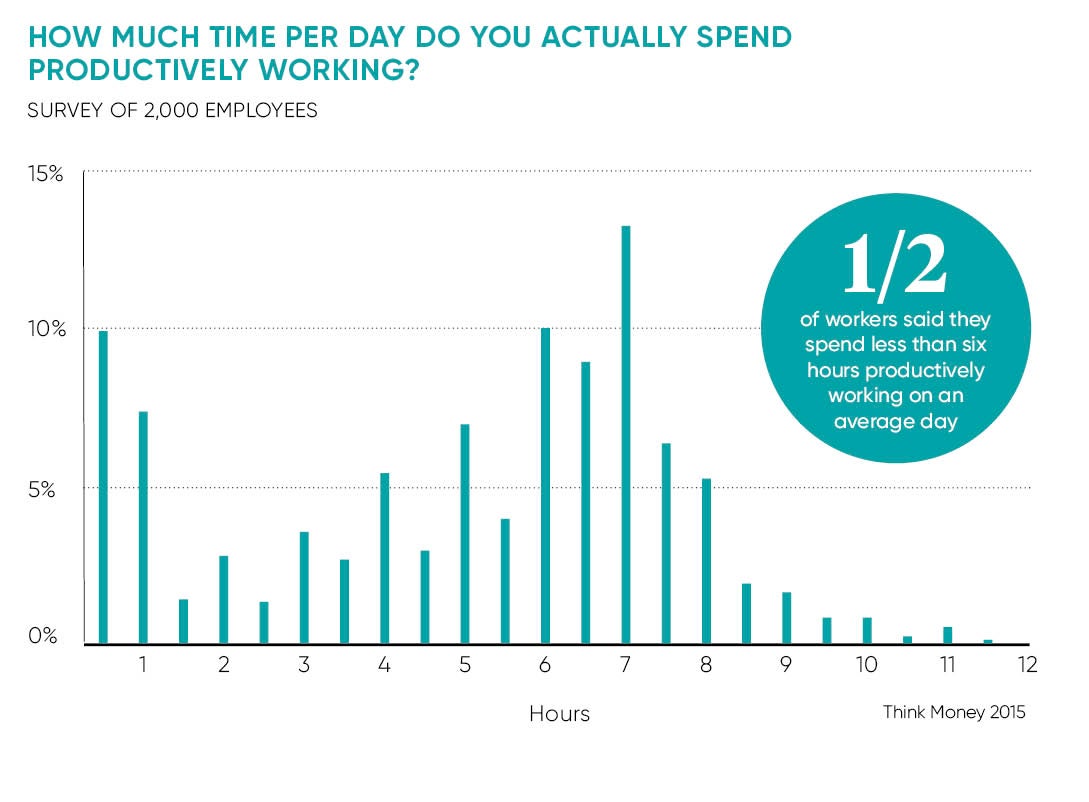

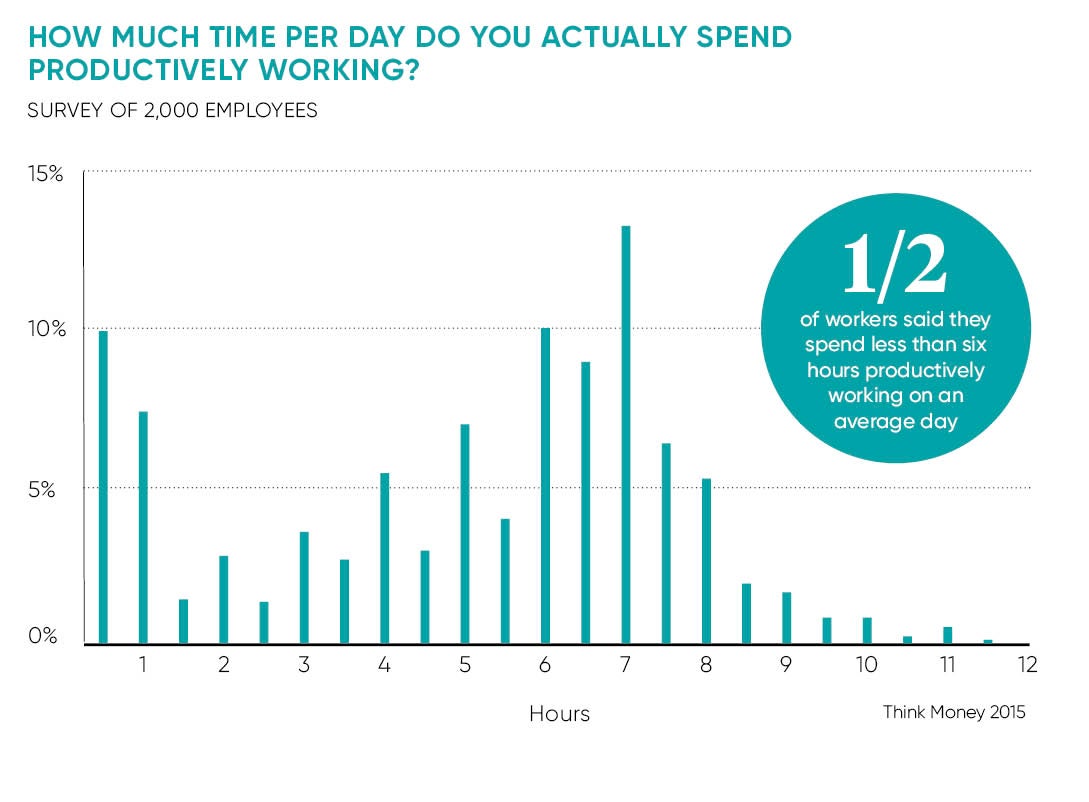

But with 73 of these occasions happening at work – tweeting, going on Facebook and using social media represents a quarter of all smart-device activity – the one group definitely not surprised is employers. A separate poll by Think Money found a third of workers are distracted for as long as three hours every day – that’s 759 hours a year.

So with the UK supposedly suffering a productivity problem, has the scale of at-work social media and smart-phone usage finally reached the point where employers have to act?

Time for action

“There’s no doubt employees are more distracted at work,” says Helen Roby at the Open University Business School. However, she questions whether the window for employers to act has already passed. “What’s also happened is that work and personal life have become blurred. Our research reveals workers now expect give and take from their bosses,” says Dr Roby.

As Aliya Vigor-Robertson, a partner at JourneyHR, observes: “Employers can’t totally absolve themselves from blame. If they demand staff to be always-on, responding to e-mails after hours, to then come down on some at-work internet usage like a ton of bricks could be seen as disproportionate.”

It’s still normal for firms to have policies around personal internet use at work. In the main, trust and common sense are applied, although a judgment by the European Court of Human Rights in January 2016 ruled employers could monitor employees’ online chats if they’re in work hours.

But while no one would want to see a return to Dickensian workhouse strictness, many feel employers are now caught between a rock and a hard place. “What’s damaging is the ‘cognitive cost’ of all this distraction,” says Nada Kakabadse, professor of policy, governance and ethics at Henley Business School. “There isn’t just time lost checking Facebook and so on, but there’s the time needed to refocus and return to the task they left. Distraction is a genuine worry for bosses because at first they were strict on online usage, then it became more relaxed and now it’s difficult to rollback from this.”

Some firms are still determined to not let social media creep into the working day at all, but part of the difficulty trying to control digital distractions is that there’s a parallel, neuroscience-based discourse that says they’re good.

“Feelings of lack of autonomy – like what you’d get from an outright social media ban – can have a big impact on the brain and people’s energy levels,” says Tara Swart, author of Harnessing the Brain Gain Advantage. “Removing autonomy creates stress and, in all my experience, the more autonomy you give people, the more productivity they actually give back.”

So is there a happy medium? Ms Swart says there is: “Managers first need to accept there’s nothing wrong with breaks per se. What they should encourage, however, is proper task-switching. Moving from working on a computer to browsing online is still being on a computer. The best thing for staff is to go for a walk and talk to people. Online time should be saved for say, lunchtimes.”

Sir Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology and health at Manchester Business School, says: “When workers only take 23 minutes for lunch, they must recharge in other ways. Short, sharp breaks away from high-intensity work can clear people’s minds and help them approach their tasks differently. Used in the right way, moderate distractions can be incredibly effective.”

For some firms, particularly those in the social media space, the offer of online freedom is actually couched as a part of the way staff can control their careers. “As a growing startup, we say developing initiative is what will grow their role, so how much time they spend seeing what’s on social media is up to them,” says Monica Karpinski, head of content at digital marketing company Curated Digital. “This is not us being some edgy startup; we find that when you give people freedom, they respect it.”

Nicholas Gill, co-founder and strategy partner at marketing agency Team Eleven, believes employers haven’t yet lost all control and that it’s still possible for them to set boundaries. “We do social media for clients, so clearly we need to spend time being involved with it,” he says. “But the one thing we do ask is that phones are not on the table in meetings. Notification bombardment is overwhelmingly distracting. We feel we need to be present and attentive to ensure meetings are effective.”

Time for action