The internet of things or IoT, which can connect any device to the web, has been a boon for owners of manufacturing firms. By providing data from multiple machines, factory performance can be monitored, goods can be tracked and maintenance needs predicted – all for greater efficiency.

Those on the factory floor have been less supportive of the change, understandably fearing their jobs will be replaced by robots and machines that “speak” to each other.

The reality, however, is more nuanced. Rather than eliminating all roles, the IoT is creating demand for a different set of skills. Many of these jobs will come from the service sector, supporting customers, and also the technology sector that supports the systems.

Positive picture

By 2020, according to the Centre for Economics and Business Research and technology firm SAS, some 182,000 jobs will be created in the UK by the IoT and big data in a range of areas.

The IoT allows traditional product businesses to become services firms. Instead of simply manufacturing and selling goods, the industry can now maintain and upgrade them, something the technology sector rather awkwardly labels “servitisation”.

IoT-connected devices link consumer goods to manufacturers’ systems, advising of maintenance and upgrade needs, the same way factory devices are connected. Washing machines or heating control systems, for example, can be fitted with sensors to detect when they are going wrong, alerting manufacturers to send an engineer. The same concept can be applied to the business world, and to a water utility’s pipes and control systems.

While the IoT may reduce the need for some manual jobs in factories, it will also create a huge new demand for service skills to maintain, create and market the systems

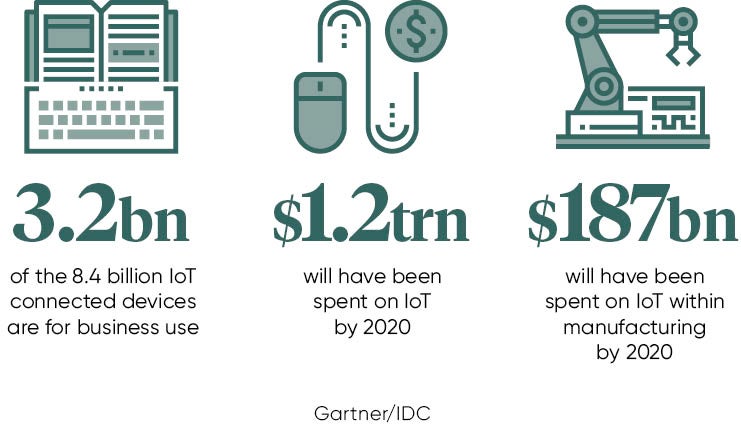

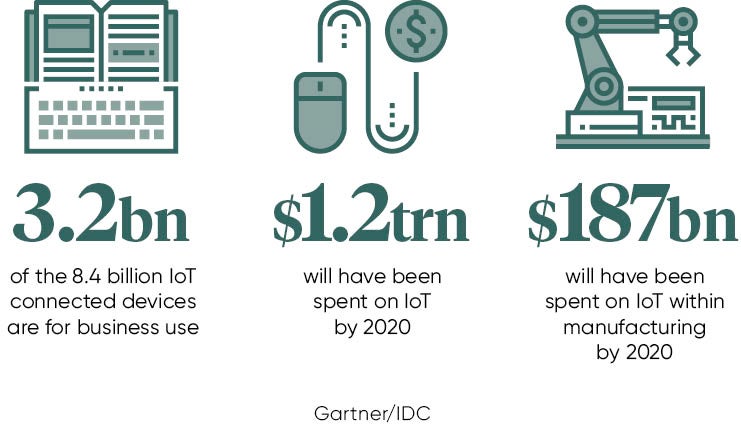

Numerous predictions demonstrate the enormous services opportunity. Gartner expects 8.4 billion IoT-connected devices to be in use worldwide this year, with 5.2 billion of them in consumers’ hands and 3.2 billion of them in businesses. Some $1.2 trillion will have been spent on IoT by 2020, says analyst IDC, with manufacturing leading the way last year with a cool $187 billion.

The change creates demand for a raft of new talent. “To capture the bigger opportunities presented by the industrial IoT,” according to management firm Accenture, “companies will especially need to look for skills in data science, software development, hardware engineering, testing, operations, marketing and sales.”

How businesses are adapting

The smartest firms have recognised this shift. Among them is General Electric, whose chief executive Jeff Immelt says industrial companies are “in the information business whether they want to be or not”.

The most positive aspects of the new service model are that it provides a deeper customer relationship and a reliable revenue stream for manufacturers. Goods makers can record customer details from which to develop loyalty and they can look forward to recurring service revenue, repairing the devices themselves or taking a cut of their contractors’ income.

Home and heating management from the Google Nest and British Gas Hive systems accumulate user data, becoming increasingly invaluable to people as they link automated services to recorded habits, making a brand switch less appealing. For their makers, both data analysis and marketing skills are essential.

This thinking is being taken a step further by expanded teams of marketing and technology personnel, who are using the IoT for immediate promotions. Drinks maker Pernod Ricard has fitted sensors to bottles that enable smartphone users to simply tap their device on the vessels to reveal recipes for cocktails and ways to buy more products. Competitor Diageo designs and runs internet-connected bottles so users can share their own videos.

An entire workforce will grow to create, sell and support the new business. In addition to sales and marketing, Accenture notes in its research, new employees “will include product managers, software developers to create and test new information services, hardware designers to develop the products, data scientists to create and interpret analytics, and user-interface and experience designers”.

Business buyers are adding to the scale of these skills demands. Rolls-Royce and General Electric have manufactured jet engines that can be sold as a service, rather than simply a product. Packaged into regular costs for airline buyers are maintenance and upgrades, with IoT systems telling them when to take action. Meanwhile, Michelin uses sensors on customers’ delivery trucks to help human experts suggest more efficient travel and sell tyres based on the number of miles driven.

As these services become the key proposition for sales forces, manufacturers can use them to drive uptake of add-on or upgrade products. The data from all of these services can also be applied by expanded research teams to influence fresh product design.

As businesses move their humans away from manual tasks, workers will equally be required to operate, design, monitor or service the IoT-linked machines they have purchased. Then there is the new demand for staff educators to help them use the systems and process engineers to make sure they fit properly into existing operations, Accenture notes.

Of course, with all these systems connecting business networks to the wider internet, security personnel will be paramount. Gartner expects that the “scarce” IoT security specialists will be in ever-higher demand and figures from freelance database Upwork show a 194 per cent increase in 2015 in demand for security infrastructure specialists.

While the IoT may reduce the need for some manual jobs in factories, it will also create a huge new demand for service skills to maintain, create and market the systems. There is no doubt that such a colossal shift will be uncomfortable for some, but the power of people will remain strong in the new world.

Positive picture

How businesses are adapting