The UK’s innovation landscape is, as you might expect, a complex picture. Innovation can be undertaken by agencies in the private, public and charity sectors and government investment in creating innovation comes from several angles.

The government spends money directly from a national budget which goes towards supporting institutions such as universities, centres for medical research and it has in the past freed up money for the development of specific areas of research such as Graphene, robotics and the Internet of Things.

Government groups such as Innovate UK were set up to partner with individuals, companies and other organisations to fuel new science and technology innovations that boost productivity, create jobs and help to increase UK exports.

Government figures published in March 2015 reveal that since 2007 Innovate UK and private sector partners have invested more than £3 billion, benefiting upwards of 5,000 companies. Across the range of programmes run by the organisation, this investment has generated at least £7 billion in value and created 35,000 new jobs.

The Catapult programme is a national network of centres created to increase innovation by companies in seven specific areas that will drive up economic growth including digital technologies, future cities, high value manufacturing and offshore renewable energy.

Catapult is funded through a mixture of a core grant and commercial funding won on a competitive basis through business-owned research and development contracts. The five-year horizon of the programme is expected to raise £1.4 billion in public and private money.

On top of grandstanding vehicles like Catapult and Innovate UK, the government also offers a range of tax incentives, grants and loans to organisations taking part in R&D. Its continual investment in education, national infrastructure and business support is a softer measure of its innovation backing.

The international innovation league

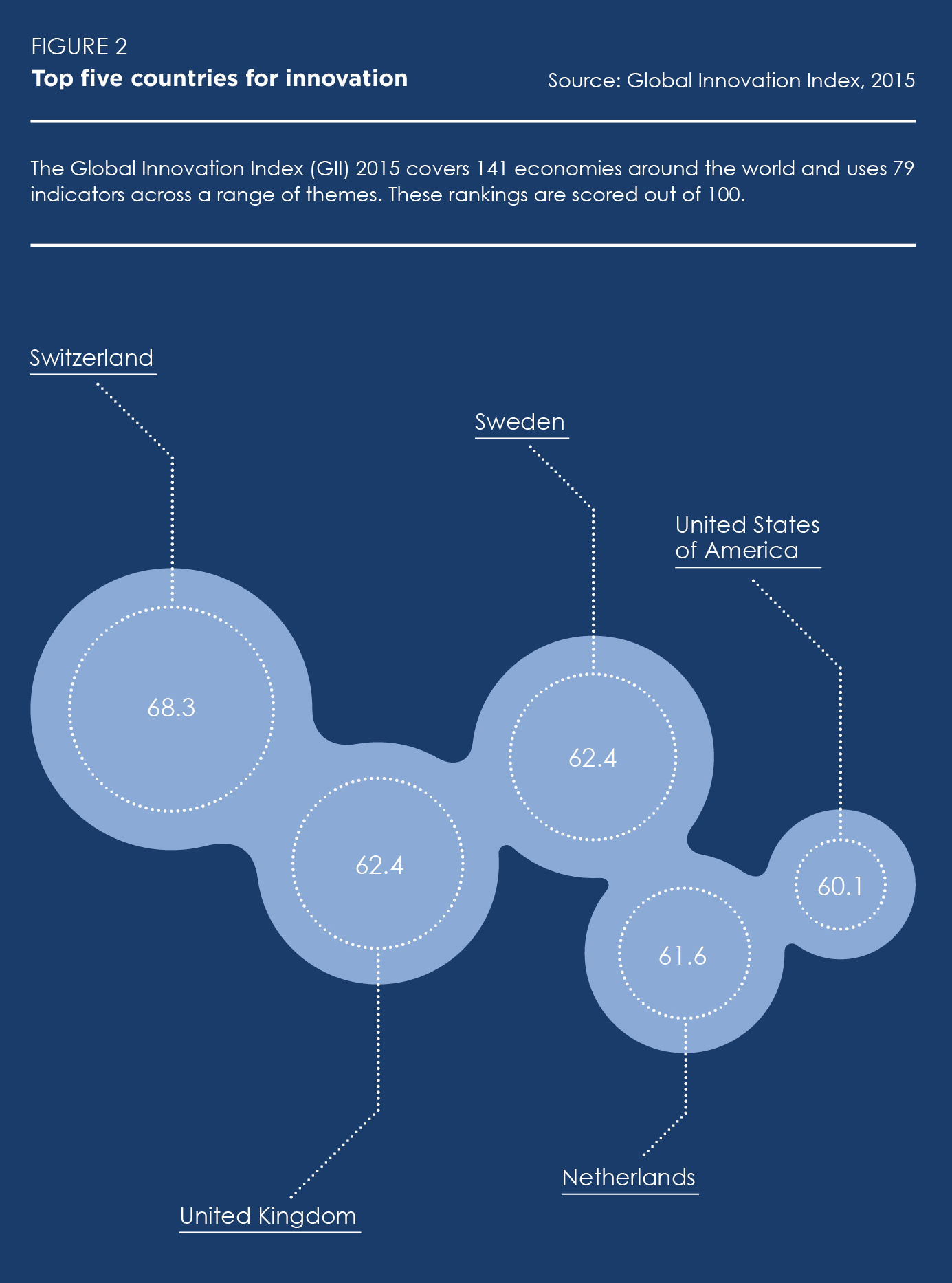

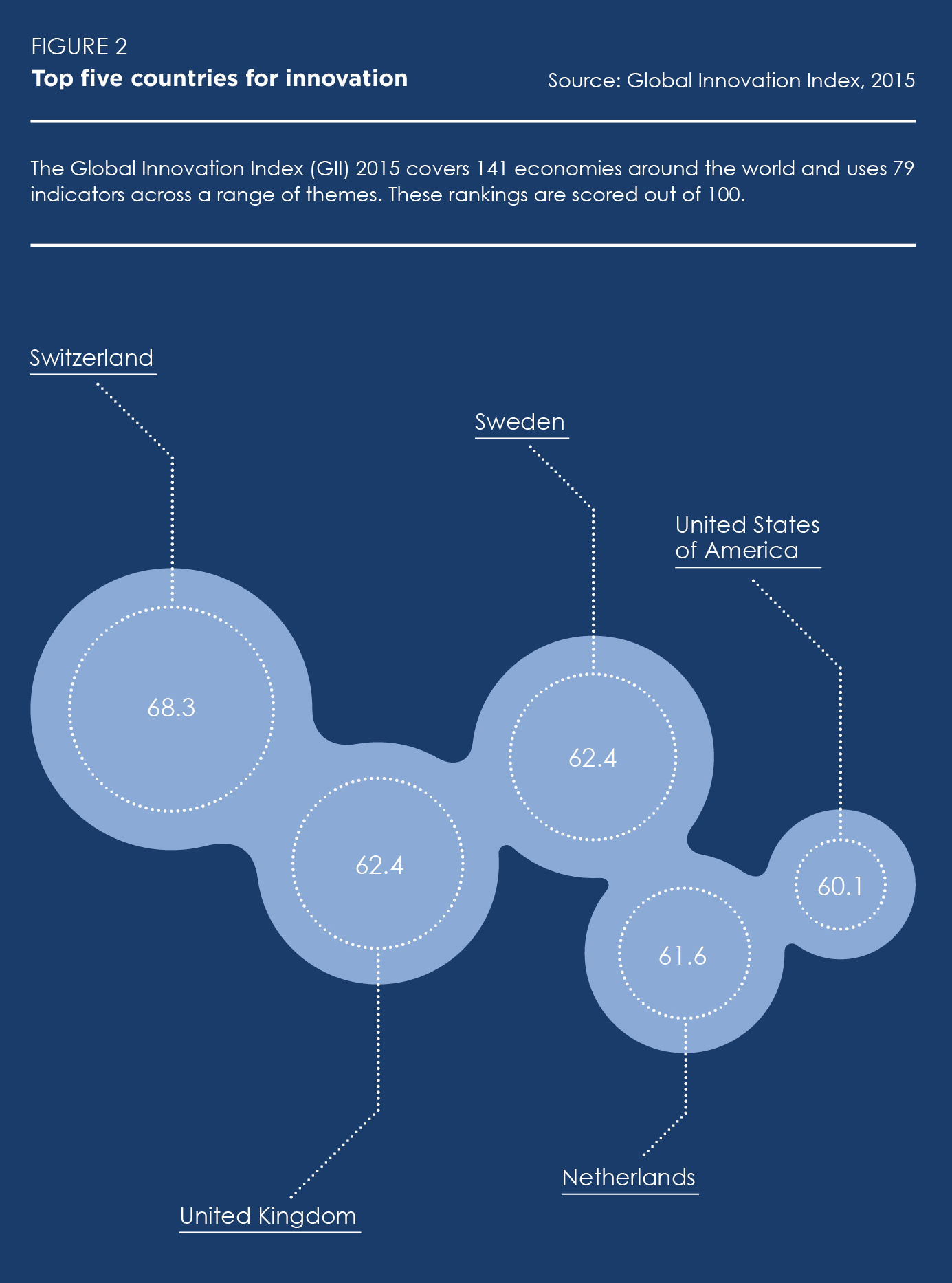

Collectively, this investment has pushed the UK toward the top of an international innovation league table. The latest Global Innovation Index (GII), a ranking of innovative countries compiled by a group of academic and research organisations including Cornell University, INSEAD and The World Intellectual Property Organisation, puts the UK second in the world.

The index takes into account a range of factors covering the public and private sectors including market sophistication, institutions, human capital and infrastructure.

Top of the list was Switzerland, perhaps surprisingly, and below the UK was Sweden, The Netherlands and the US respectively. South Korea and Japan, widely considered two countries with many of the world’s most innovative companies, failed to make the top 10.

Speaking at the launch of the report in September 2015, business minister Baroness Neville-Rolfe said: “The UK has soared ahead in these global innovation rankings over the past few years, a further sign that our long-term economic plan is working.

“We have an outstanding tradition in producing the very best in science and research: with less than 1% of the world’s population we produce 16% of the top quality published research. This is a major factor in the UK maintaining its position at number two in the 2015 Global Innovation Index.”

Yet the picture is mixed. Published in July 2015, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index ranks what it estimates are the top 10 most innovative countries in the world. The UK doesn’t feature at all, despite countries like Finland, Israel and Switzerland riding high in the top 10.

The bigger picture

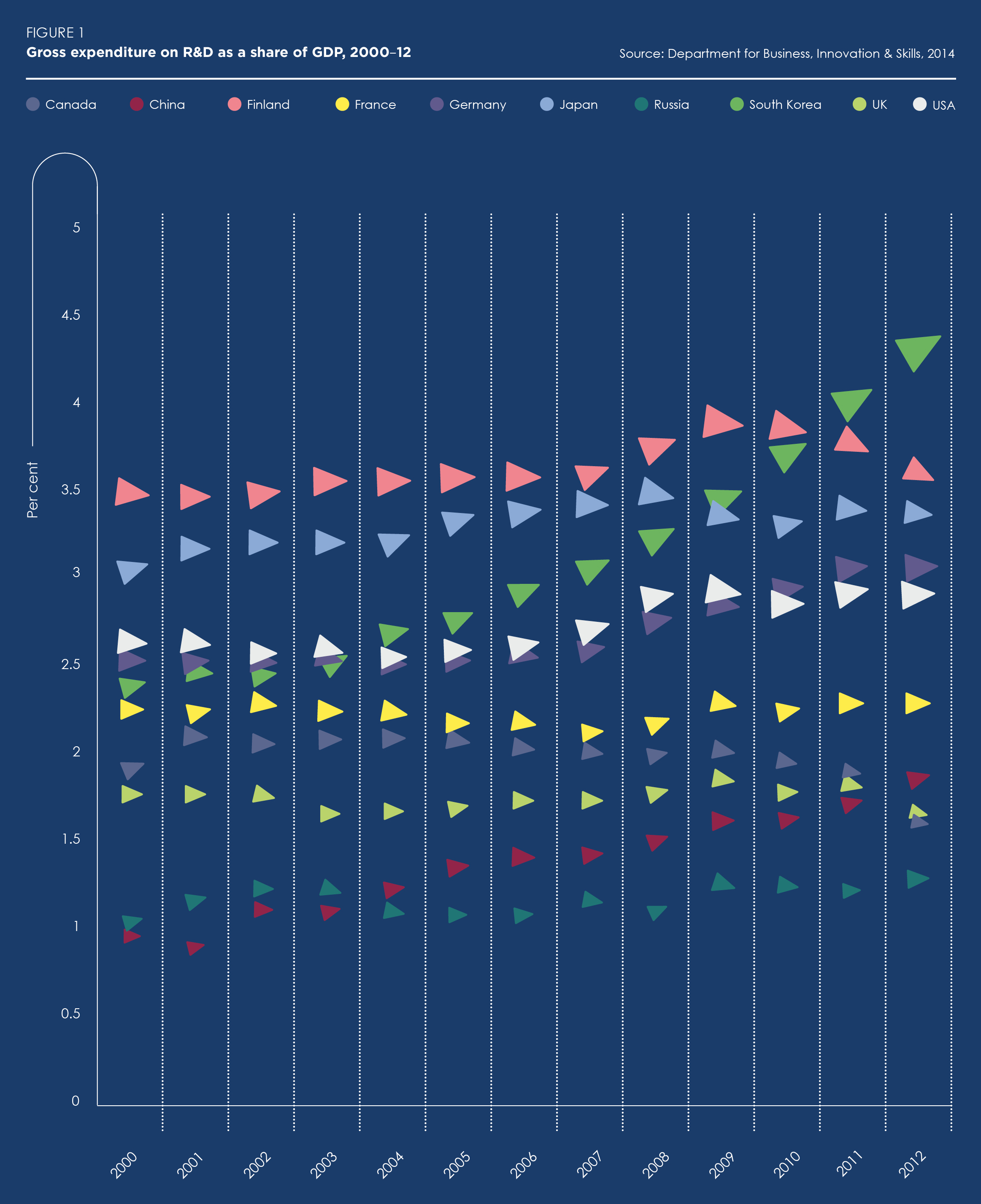

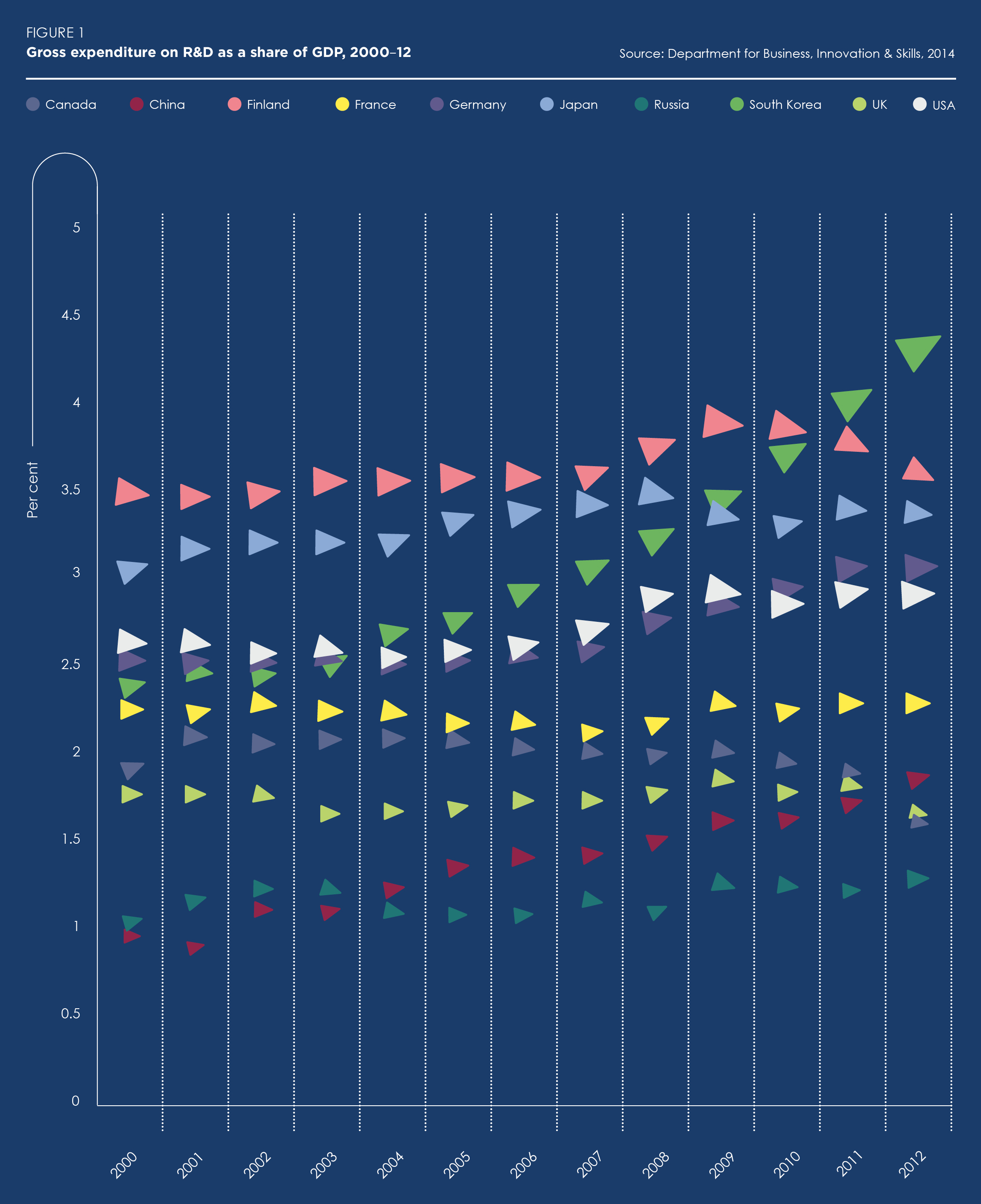

If it’s true that the UK is just about top of the pile in the value-added industries then it is not powered by the country’s economic clout alone. The newest figures show its gross domestic expenditure on R&D was just under £29 billion in 2013.

Adjusted for inflation the figure was 5% higher than the year before but the figures also show that almost two-thirds of R&D expenditure was performed by businesses, not government groups.

Meanwhile, as a share of total GDP, investment in innovation was just 1.67%. This was up slightly from 2012 but still well below the top spenders globally. The expenditure was significantly under the EU average of 2.02% and only twelfth highest in the 28-member bloc.

Compared to the US, UK expenditure is vanishingly small. In 2013, the US’ federal budget alone was nearly $141 billion (around £93 billion at today’s conversion rates). According to World Bank figures the country spent nearly 2.8% of its GDP on this area between 2011 and 2015.

Other developed countries also outstrip the UK by a significant margin. In the same timeframe, Sweden spent 3.41% of its GDP on research, Japan 3.39% and Germany 2.92%. Even countries outwardly lower down the innovation pecking order spent more, including Belgium with 2.24%, Austria with 2.84% and Denmark with 2.98%.

Meanwhile, anecdotal evidence is emerging that could be a warning sign to ministers. Research released by consultancy Rare: Consulting in November revealed that only 22% of UK workers feel confident their organisation will meet current innovation demands.

The UK’s standing as a beacon of innovation excellence is beyond dispute, but less certain is whether the country is coming to the end of a golden era

The main barriers to adoption include poor organisational culture, cited by a third of respondents; a lack of education, claimed by three in 10 and a failure of departments to work in a connected way, cited by a quarter of people taking the survey.

David Edmundson-Bird, associate director of digital innovation at Manchester Metropolitan University, which partnered with Rare: Consulting for the research, said: “This snapshot of UK business innovation should act as a warning from the future. We are at a pivotal moment in economic and social development in the UK.”

The UK’s standing as a beacon of innovation excellence is currently beyond dispute, but less certain is whether the country is coming to the end of a golden era of innovation and what the future holds. Without redoubled investment in this area, the world’s emerging economies – as well as established ones across Europe – could begin to push the UK further and further down the world rankings.

The international innovation league

The bigger picture