There’s a new kid in the boardroom – a character sporting a pair of clever-clog spectacles and a monster-sized brain.

The newbie has muscled into a space at the big table between the chief financial and chief technical officers. This new role is the chief intellectual property officer (CIPO) – and some are suggesting that before long, no board will be complete without one.

CIPOs are not always given that label; some have rather more elaborate titles, such as heads of intellectual asset and innovation partnership management. But the reason they are cropping up in various forms at large corporations is twofold: an ever-increasing importance of intangible intellectual property (IP) assets to bottom lines; and a hitherto woeful lack of IP knowledge among top executives.

Recognising the importance of IP

Brian Hinman is a perfect example. At Amsterdam-based global conglomerate Philips, he even travels under the straightforward description of CIPO.

Mr Hinman claims his business has been at the forefront not only of IP innovation, but likewise it has led global boardrooms in recognising the vital role of this intangible asset.

His post was created 20 years ago, the result, he says, “of the recognition by the C-suite in Philips of the extreme importance of its IP portfolio and strategy, and the need to have a seasoned business executive to establish, guide and implement this strategy”.

He explains: “At Philips, IP is a separate business with a separate profit and loss responsibility, which is taken very seriously by every business group within Philips.”

All well and good, but is Philips alone in that recognition? Mr Hinman says large counterparts are following suit, “but with inconsistent views on the overall responsibility that each CIPO has”.

Boardroom ignorance

The Philips man is also critical of the approach of many businesses, which continue to view IP as a befuddling and complicated issue, seemingly suitable only for esoteric minds in legal departments. “[That] is not the appropriate home for it,” he argues. “A company needs to define what strategy it would like to employ with respect to IP – offensive or defensive licensing, enforcement, exclusivity, or a combination of any or all of those – and then build a business organisation that is equipped to handle that strategy.”

Others in the IP world are far less diplomatic about what they see as dangerous boardroom ignorance. “It is surprising how uniformed people are,” says Neil Nachshen, a partner at London-based trade mark and patent attorneys D. Young & Co, before acknowledging that boardroom awareness of IP issues varies among corporate sectors.

For example, those sitting around the big table at a global pharmaceutical business will all be aware of impending patent expiration issues. But, claims Mr Nachshen, even in the software and electronics sectors, awareness levels drop dramatically.

A core problem is that some boards are not encouraging their in-house legal teams to provide training and strategic insight to IP issues

“The position is improving,” he says, “but there is still not a full appreciation of the value of IP to their companies – how the whole IP portfolio can be managed and leveraged to create business. There also seems to be a low awareness about the patents you can get for software-related inventions.”

A patchy understanding

Morag Macdonald, joint head of the international IP group at London law firm Bird & Bird, is equally critical. “IP is absolutely essential in areas such as online retail and mobile banking,” she says. “Trade marks underlie the online branding of apps. Yet the understanding of IP and how it affects these areas of business is extremely patchy at board level.

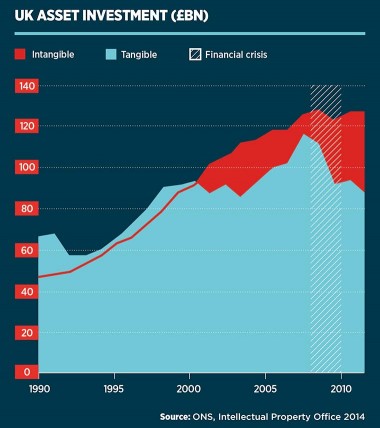

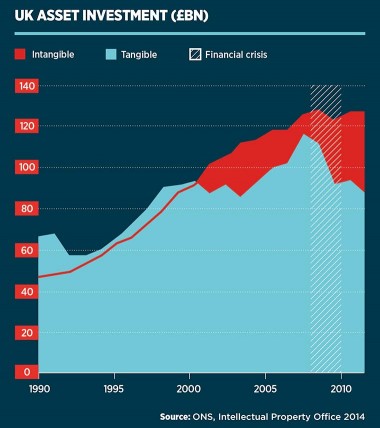

“And that is very dangerous. A board would be uncomfortable not understanding the way the rest of its asset flow is going. So I cannot understand how they can be happy not understanding their intangible assets in the same way they understand their tangible assets.”

According to these specialists, a core problem is that some boards are not encouraging their in-house legal teams to provide training and strategic insight to IP issues. In a hectic corporate world, doing so just falls fairly low on the agenda.

Therefore, in many cases, the first time a board becomes aware of its business’s intangible assets is when a problem arises, either because a competitor business is infringing their rights or enforcing intangible asset rights against them. By that time, it is far too late to have a crash course in IP basics and the only option is to instruct litigation lawyers.

Matthew Pryke, an IP specialist partner at London West End law firm Hamlins, summarises bluntly: “Chief executives are a distance away from truly understanding the value of IP for long-term business growth. Too often executives view IP in terms of costs and legal compliance.”

Attitudes are changing

But other leaders in the IP field take a slightly more positive view of the evolution of boardroom knowledge. Nigel Swycher, chief executive of IP consultancy Aistemos, says: “With increasing frequency, IP has entered the boardroom and directors are recognising now that the bulk of their business’s asset value is associated with areas that are less easy to put a finger on. And those areas are getting closer attention.”

According to Mr Swycher, the key ingredient for chief executives and their directors is more and better information. “Boardrooms are screaming for data in this area,” he says. “They are screaming for more aggregation of data and more competitive intelligence. And as that water level rises, everyone is trying to be more helpful so the chief executive can make the best decisions. Executives need to focus on what matters – and IP now matters.”

So just what are the hammers and spanners that boardrooms need to ensure are in a business’s IP strategy tool kit?

IP portfolio strategy

The starting point, says Kenneth Mullin, partner head of IP at London law firm Withers, is “senior management buy-in”. That includes a process in which the top team assesses the intangible assets its business is sitting on.

“Sometimes businesses don’t recognise their own IP,” says Mr Mullin, “perhaps because they’ve never thought about it. And sometimes it goes the other way – people over-estimate the value of their intangible assets.”

Part of that nuts-and-bolts exercise involves recognising obvious IP, such as registered trade marks and patents, as well as assessing more ethereal parts of the business, for example, know-how and goodwill.

Executives need to ensure their businesses have sufficient protection in place, namely legal documentation of intangible assets created by employees or contractors. They must guarantee those rights are passed on to the wider business.

Likewise, businesses must register rights in all countries and jurisdictions where they are operating. And crucially, rights must be policed and enforced. Mr Mullins explains: “In some jurisdictions you can lose rights if you don’t enforce them properly.”

Bird & Bird’s Ms Macdonald adds that a vital task for boards is to conduct an IP audit so businesses know exactly what they have in the bank.

“Many companies think it is just what they have registered, but that might not be the case,” she says. “They might not have the right things registered. And often companies only do this when they are going through an acquisition or a sale during due diligence.”

All in all, it’s enough to keep those new kids on the board extremely busy. Mr Hinman, CIPO at Philips, concludes: “Without a strong IP portfolio and strategy, a company is left naked with respect of being able to confront the challenges it will face in implementing its overall corporate strategy.”