From iPhone cases to Christmas decorations and meat grills, merchandising is a blockbuster business that can turn intellectual property into gold.

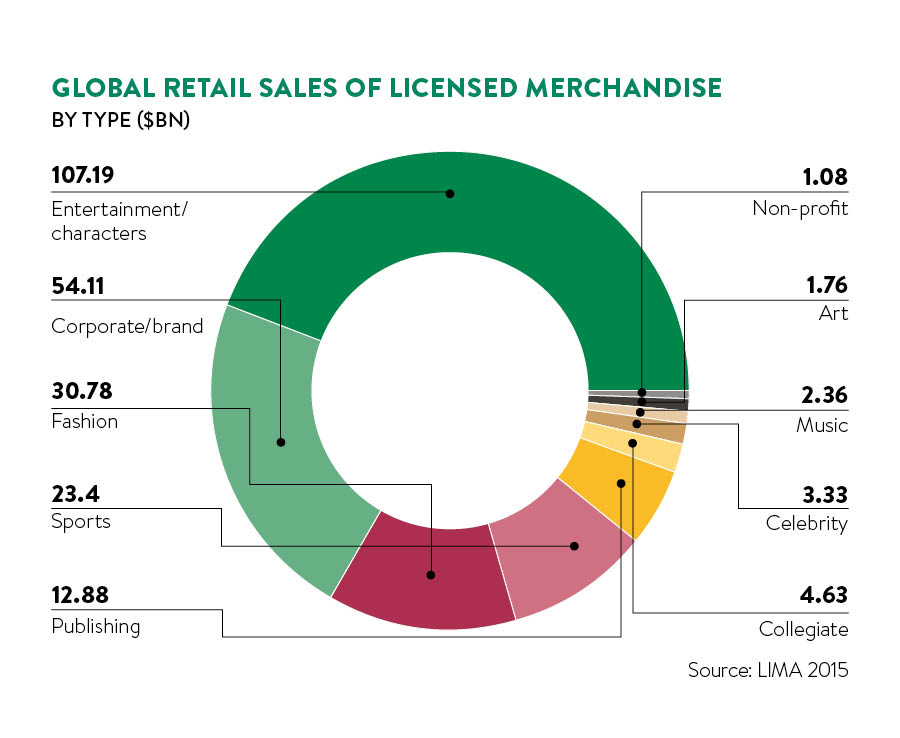

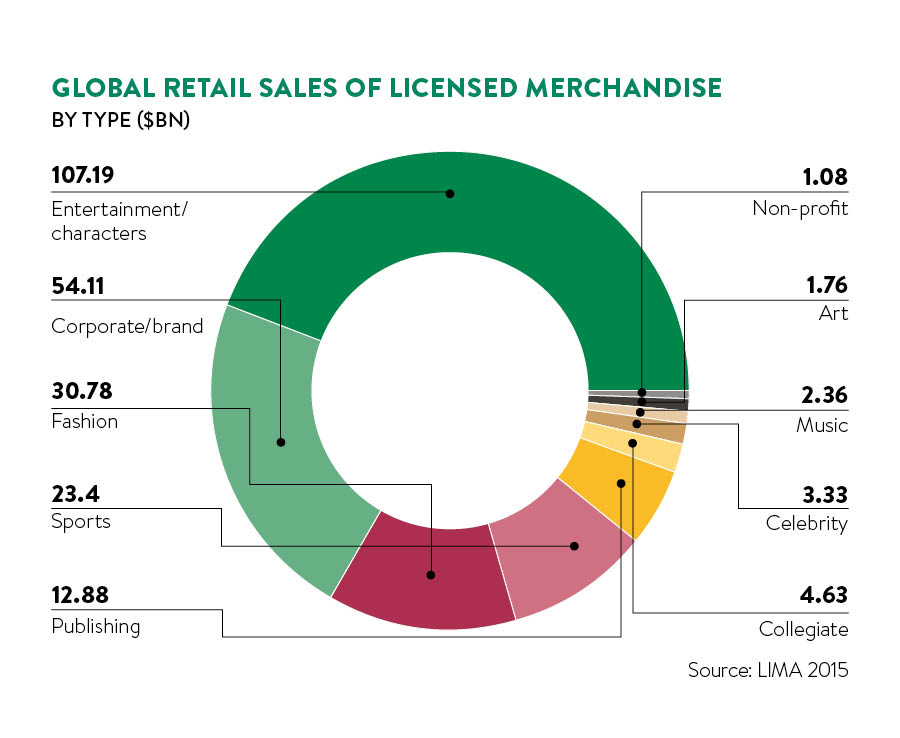

Global retail sales of licensed merchandise and services reached $241.5 billion in 2014, generating royalty revenue for IP owners of $13.4 billion, according to the International Licensing Industry Merchandisers’ Association. Famous brands such as Disney, with its slick licensing operation, made up a large proportion of that figure, earning hundreds of millions of dollars from the sales of consumer goods.

But it’s not just Star Wars and the like that can benefit from leveraging IP; anyone with IP assets should be considering what sharing their brand could do for the bottom line.

There are two sides to the licensing industry: those who own IP rights and sell them for use on goods and services; and those who buy rights to use on goods and services. The purpose is largely the same for both – to raise revenue – but there are other benefits too.

A win-win deal

Generally speaking, an IP owner licenses its brand into new areas in exchange for royalty payments (licensing out), while the licensee exploits the popularity of that brand in order to shift units (licensing in).

For some cash-cow brands there is almost no such thing as a bad licensing deal (Downton Abbey curtains, anyone?), but most need carefully to manage who they sign deals with and where their precious IP ends up. Paired with the wrong product or service and a brand’s reputation can take a serious hit. A carefully crafted deal, however, is well worth the effort and mutually beneficial for both sides.

Product manufacturers know that an affiliation with an established brand can give them the edge and will leap at the chance of partnering with a movie, TV chef or even a famous landmark.

“Revenue is a very important part of why a licensor would license out their IP, but not the only reason,” explains Kelvyn Gardner, managing director of the International Licensing Industry Merchandisers’ Association in the UK. “Licensing into areas outside the core product also helps to protect the brand.”

Joel Smith, head of trademarks and brands at law firm HSF, regularly structures such deals.

“It’s very common,” he says. “There are lots of advantages and it’s relatively lucrative if a product does well. There are very few companies that want to open local subsidiaries with local employees and manufacturing facilities themselves.”

The IP division of a business used to be seen as purely enforcement, protecting the company trademarks, patents or copyright, but now it can be a hub of opportunities for a business to grow, diversify and pick up lucrative royalty fees.

The trend in favour of creatively licensing out IP has driven a shift in boardroom attitudes towards in-house lawyers. A more proactive approach is the now the norm, including establishing licensing arms within the business and employing licensing officers tasked with approaching potential partners.

“A lot of businesses have moved from knowing about their core IP assets to realising everything they own that has IP protection could be a source of revenue, so IP is seen as a profit centre,” says Mr Smith. “Companies that received unsolicited requests would have, historically, been ignored, but now people think, ‘there’s an opportunity there’.”

Securing trademark protection

The best approach is to create a licensing strategy from the very start. If a brand takes off, it can pay dividends later on, leaving the company to concentrate on the day job.

As Matthew Sammon, UK head of trademarks at Marks & Clerk, explains: “Securing trademark protection at the beginning of a brand’s life cycle is important for the growth of any business, but it has to develop as your business grows.

“If you have trademark protection in place for potentially merchandisable products, you can license out the trademark rights for a royalty fee, and let others take on the expense and work of manufacturing, advertising and selling the actual merchandise.”

Reacting quickly to ensure your trademark protection matches your expansion plans is essential, advises Mr Sammon, both in terms of the countries where your mark is registered, and the types of goods and services it is registered against.

Registering a brand in all 45 trademark classes costs a lot of money and many of them will go unused. However, leave out a class and the business may discover people piggy-backing on its IP, forcing costly litigation further down the road.

Rolls-Royce is unlikely to make a vacuum cleaner any time soon, but that could leave the door open for another company to launch “Roller Royce” and get away with it. IP chicanery of this sort could be stopped by trademarking the brand for use in vacuum cleaners, then licensing out the mark to a specialist manufacturer.

Branching out to consumer goods

The cash generated by licensing can also be essential to growing a business’s core products. A company can continue doing what it does best, while in the meantime earning significant passive revenue.

There are some IP owners who license out for more subtle reasons. You wouldn’t expect tyre maker Michelin to run Michelin Lifestyle, side project licensing footwear and bicycle accessories. Or, indeed, the world’s most famous restaurant guide.

“What the licensing programme does for Michelin is allow its brand to be exposed to the customer far more regularly than would be the case if it only came up in that two-to-three-year period when they have to buy new tyres,” says Mr Gardner. The aim is to cement the Michelin name in the mind of the consumer ready for that time when tyres are needed.

Disney generated $4.5 billion in annual consumer products sales last year, helped by merchandise licensing from movie franchises such as Frozen and Star Wars

Mr Gardner believes every brand in the world can find some consumer goods or services to license to and equally consumer goods or services can always find an established brand that would add value.

The rules work for anyone who owns IP; however, a brand needs to achieve some degree of public awareness before a manufacturer is likely to pay attention.

“A smaller brand won’t have the same degree of brand power,” Mr Gardner concedes. “However, it’s not impossible by any means, if you can get in front of enough consumers then the market can almost create itself and retailers will buy into the product in reverse – they may hear a groundswell of popular opinion is looking for something then approach the manufacturers.”

Shopkins is a good example. If you know any girls under 13 then you have probably already heard of the grocery-inspired collectable toys (think a chocolate bar with a cute face). If not, then all you need to know is that some of the rarer figurines are trading on eBay for £200 a pop.

The brand came from nowhere to become the number-one selling toy in the United States last year, helped by a large range of licensed goods. It’s currently one of the most licensed girl products in the UK, slogging it out with Disney’s Frozen.

“Things can take off really quickly if someone tweets [your brand] or a celebrity endorses it,” HSF’s Mr Smith concludes. “You’ve got to be prepared to take advantage of that and get it out other markets, which may not be your nearest one.”

CASE STUDY: ANGRY BIRDS

It is a huge success story. A mixture of our feathery friends, evil pigs and seriously satisfying game mechanics that, for a while at least, was the world’s most popular game.

It is a huge success story. A mixture of our feathery friends, evil pigs and seriously satisfying game mechanics that, for a while at least, was the world’s most popular game.

But the company behind the smartphone legend and now blockbuster movie Angry Birds was just as adept at creating a licensing business worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Finland’s Rovio Entertainment initially applied for an international trademark covering a small range of products in 2010, a year after releasing its first game.

For cost reasons it made sense to apply for relatively narrow protection to begin with, but when the brand went viral and myriad merchandising opportunities appeared, a wider scope of protection was needed, and in 2011 it expanded to 17 classes, encompassing a vast range of goods, from bags to rugs and jewellery.

Few entertainment companies like Rovio have in-house clothes or stationery manufacturing facilities, so licensing out the brand to other manufacturers and charging them royalties for products bearing the Angry Birds brand was a sensible move.

For the licensee, “licensing in” can give your goods an edge over competitors. “Licensing in a famous brand like Angry Birds can provide merchandise manufacturers with a great commercial opportunity,” says Matthew Sammon, Marks & Clerk UK head of trademarks.

“If they can approach a retailer with the prospect of supplying branded merchandise, it opens the door for more supply contracts further down the line. They may even be able to secure deals to supply their own branded goods to the retailer off the back of a deal to supply licensed merchandise.”

A win-win deal