Shockwaves from the tsunami of the biggest personal data hack, into Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, are still hitting politicians and celebrities worldwide. Believed to have been orchestrated at the behest of the US government, it is but one of an almost weekly assault on organisations’ digital data, joining the line-up which already included the likes of Carphone Warehouse and Ashley Madison.

But for many businesses, it is the growing threat that cyber crime poses to the security of not their personal or customer details, but to their intellectual property or IP.

Protecting intangible assets

Robert Williams, partner and co-head of the London IP group at lawyers Bird & Bird, says: “The value of intangible assets is such a significant proportion of a company’s market value these days that it is critical to protect.”

A 2015 report from US consultants Ocean Tomo reveals that the average intangible asset value of the Standard & Poor’s top 500 firms is 84 per cent.

Theft of IP is a growth industry, providing good returns at low risk. And the impact on those affected can be devastating to their reputation, profitability and survival.

Beyond the loss to the individual companies, Ed Lewis, partner specialising in cyber, data and privacy at Weightmans, says IP crime has a wider impact on innovation and on the ability of western companies that are frequently the targets, to sell their goods at a competitive price.

“It has a direct impact on the GDP of western economies, but people do not make the macro-economic link,” he says.

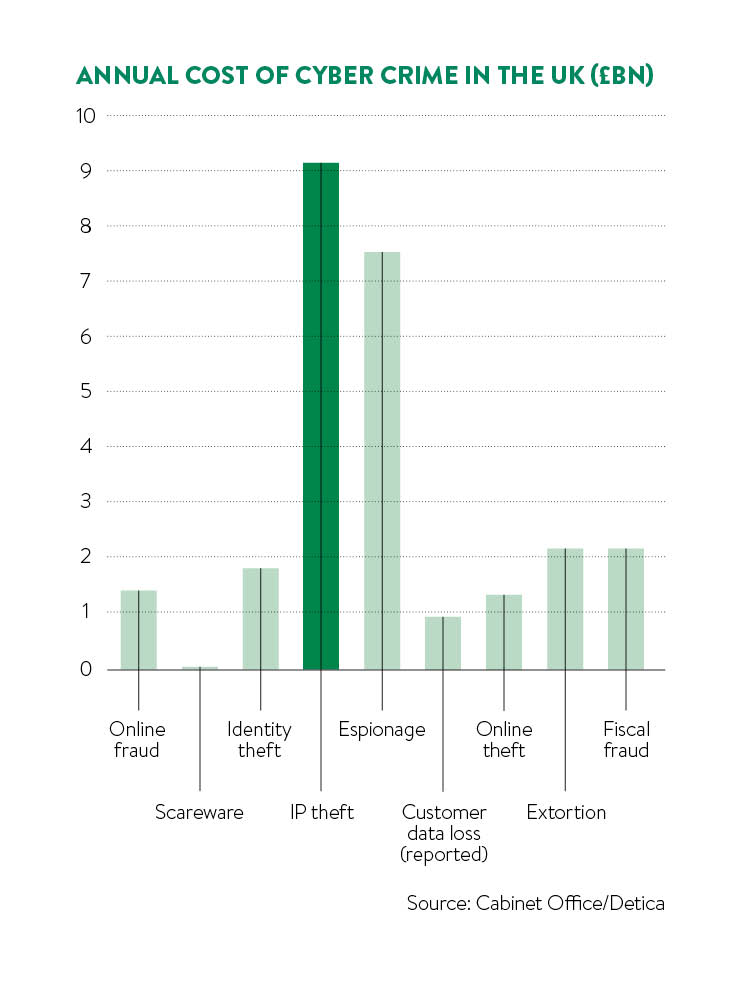

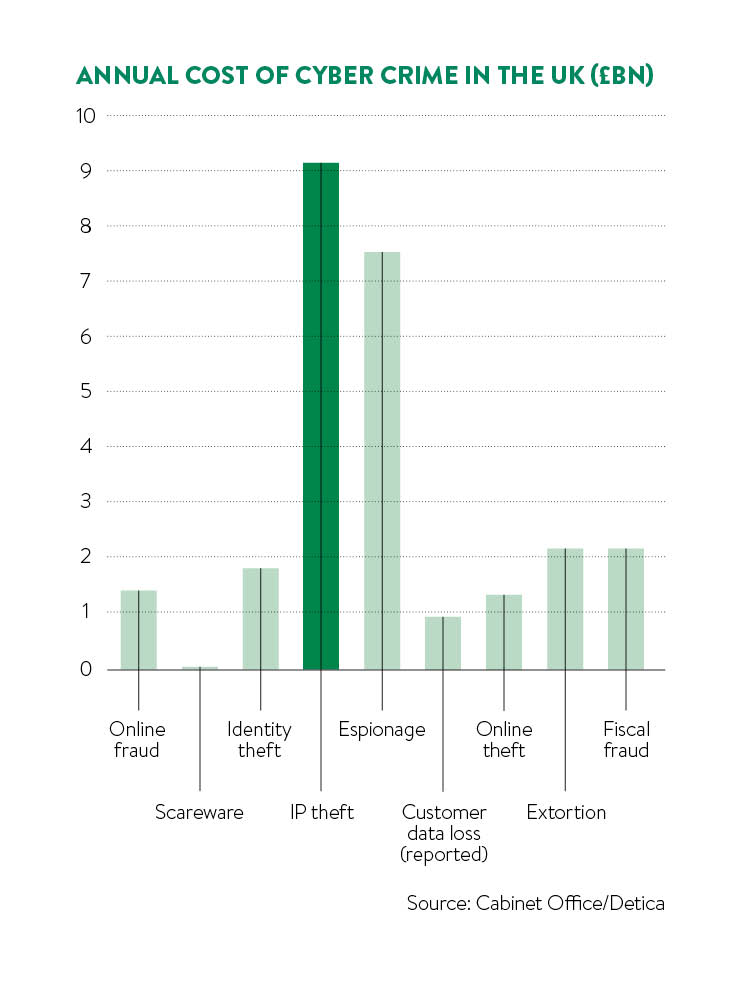

Estimating the cost to businesses is tricky, as most incidents go unreported. A report from US global computer security software company McAfee estimated that high-income countries lose on average 0.9 per cent of their GDP because of it.

But, says Mr Lewis: “You need to take the statistics with a pinch of salt as the scale of the problem is more significant than they suggest.”

Internal and external threats

It is not a new phenomenon, but the internet has made it easier, and methods have become more sophisticated and harder to detect, says Michael Edenborough QC, IP barrister at Serle Court chambers.

“In the old days, you had to physically break into an office and steal or photocopy pieces of paper. Nowadays you can be sitting in Romania and hack into a computer in Australia,” he says.

The threats come from three main sources – external, internal and bad or old IT that means your systems lack resilience – says Stewart Room, partner and global head of cyber security and data protection at PwC Legal.

The insider threat is commonly employees exhibiting Laurel and Hardy-style cyber security. With “fat-fingered negligence” they send an e-mail to the wrong person or accidentally open a contaminated message, says Mr Room.

There may also be motivated insiders, who are disgruntled, have criminal intent or see themselves as whistleblowers.

Externally, hacks can be from organised criminal gangs. It is far easier and safer to steal trade secrets than it is to smuggle heroin, and the penalties if you get caught are lower, observes Mr Edenborough.

There are those in the hacking community who do it just to show that they can; hacktivists, who do it to further an agenda. Then there is the most sophisticated of all, state-sponsored industrial espionage; hacking that is sanctioned and funded by nation states in order to get technology from more advanced countries.

Surveillance state whistleblower Edward Snowden claimed Chinese hackers had stolen Pentagon blueprints for the F-35 stealth fighter jet, similar in design to the subsequently built Chinese J-31. Chinese officials denied the allegations and the Pentagon admitted breaches, but said no secret information had been taken.

North Korea dismissed the notion that it played a hand in the Sony hack in retaliation for its release of the film The Interview, depicting a fictional assassination of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

A plethora of techniques

The techniques to gain a foothold in targeted organisations are manifold, says David Kennerley, senior manager for threat research at online security experts Webroot. They range from opportunistic “phishing” e-mails containing malicious files, to e-mails pointing to websites that fraudulently collect login credentials.

Tom Phipps, a partner in the IP team at law firm Ashfords, adds “man-in-the-middle” attacks where the attacker secretly intervenes in communications between two parties who believe they are directly communicating with each other.

Other methods, says Mr Kennerley, require more planning. For example, “watering hole attacks” where a website that employees are known to visit regularly is compromised with the intention of serving malware to the employees through the site.

“The initial aim of any attack is usually to obtain login and network credentials or run malware with remote access capabilities, so it can be controlled from another location,” he explains.

Most commonly, hackers target a link in a company’s supply chain, usually a trusted partner, on the basis that their security may be weaker, says Andrew Beckett, managing director of cyber and investigations at Kroll.

In the event of a serious breach, the initial impact will be the “organisational chaos and distress” felt at a human level, says Mr Room.

“The stress levels are truly awesome in a serious case. I’ve had people at their wits end, in tears and who haven’t slept for days,” he says. “Everything you have to do after a breach will be so new – calling the police and dealing with the regulators and angry business suppliers. The peculiarities, uniqueness and novelty of it have a massive strain on the mind.”

And when the worst happens, says Mr Phipps, you must have plans and procedures in place to respond and mitigate the impact, including a strategy to minimise adverse press coverage.

Building a robust security strategy

The rise of mobile working and reliance on cloud computing heightens risks and increases the need to minimise threats. Mr Room advises first understand what is important to you and what is IP.

Thorough risk assessments, and robust policies and procedures are essential, Mr Phipps adds.

While Mr Kennerley advises organisations to build a comprehensive “living” security strategy, keeping abreast of industry information and security bulletins, and following best practice.

“Security and IT staff need be trained in how to maintain and manage any deployed systems; they need to understand the alerts and log information, and to act appropriately when abnormal behaviour is detected, as well as regularly testing their incident response plan,” he says.

But technology is only part of the solution. What is required is a combination of internal systems, monitoring and, crucially, education to ensure all staff understand the risks.

Kroll’s Mr Beckett recommends companies write security standards into contracts, either information security standard ISO 27001, published by the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission, or the Cyber Essentials Scheme, developed by the UK government.

In addition to firewalls and appropriate security systems, IP barrister Mr Edenborough says companies may have two computer systems – one linked to the internet and an intranet that can only connect to the internet through an authorised gateway or is entirely isolated.

He also suggests companies hire “poachers turned gamekeepers”. “I’d expect organisations of any size to a have a dedicated internal anti-fraud unit, staffed by a mixture of legitimate scientists and former police officers, and people of a less transparent background,” he says.

However, Mr Edenborough concludes: “Whatever you do, there is very little that the determined person can’t get.”

Protecting intangible assets

Internal and external threats