If you know anything about protecting your intellectual property across Europe, you’ll be aware that you can apply for a European patent under a treaty signed as long ago as 1973.

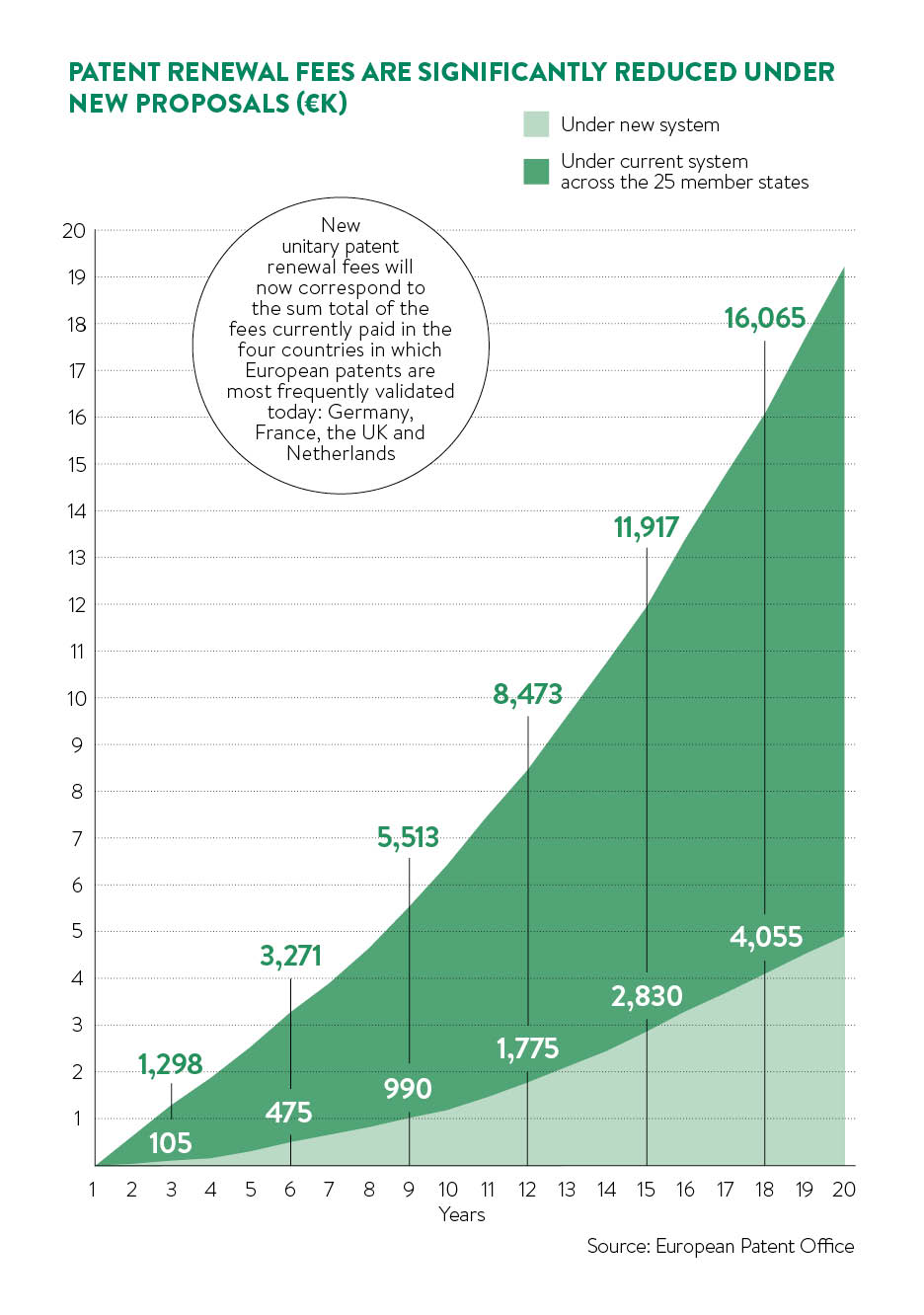

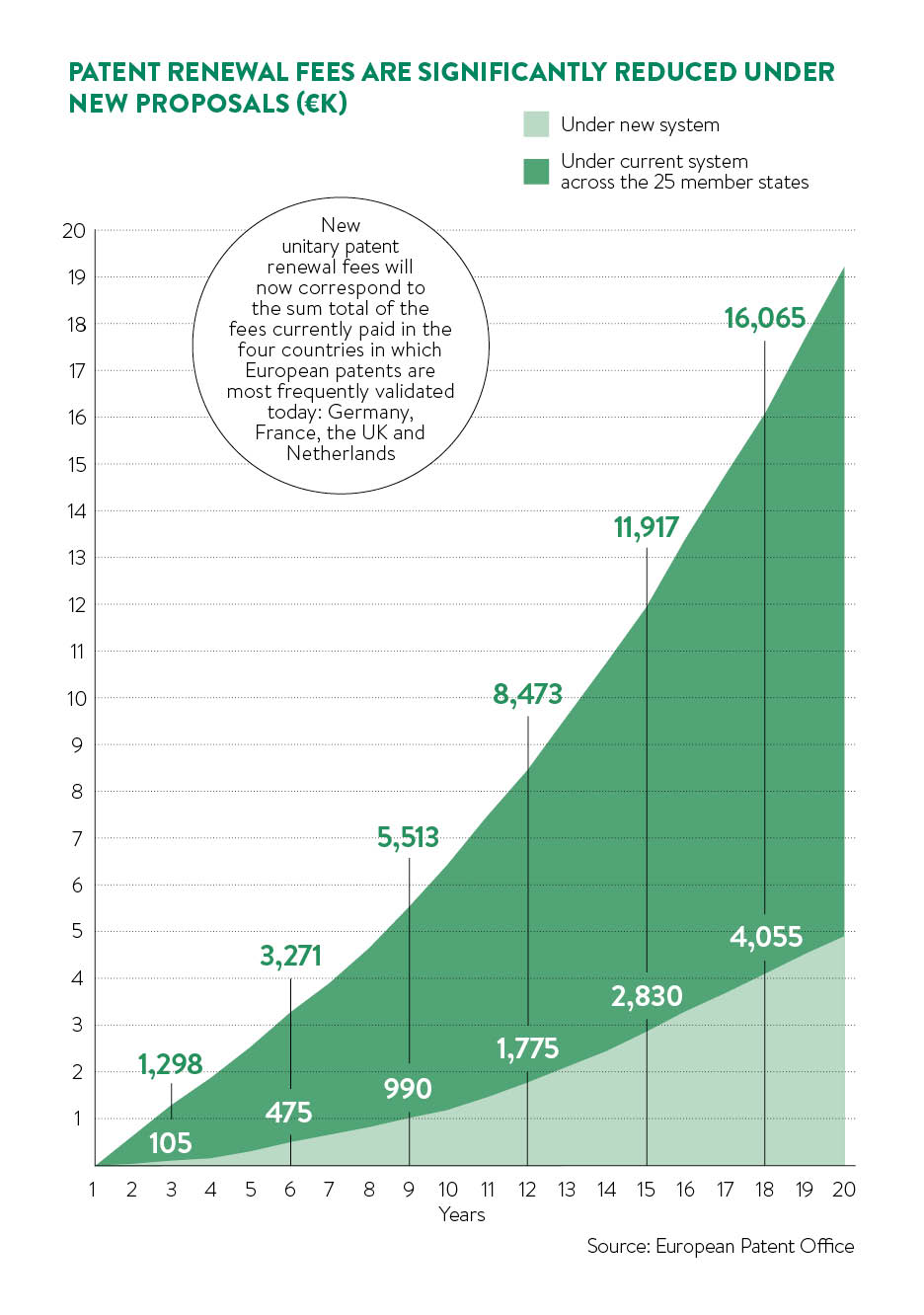

At the moment, though, all you get under the European Patent Convention is a bundle of individual national patents. You still need to validate those patents in the countries where you want your invention protected. That’s likely to involve translation into the local language as well as more paperwork and higher fees.

Worse still, if your invention is any good and your competitors try to copy it, you have to bring infringement proceedings in each country where your intellectual property is at risk. You may end up arguing the same case against the same defendants at the same time in different national courts.

The unitary patent

Sometime early next year, all that is expected to change. Single European patents will continue to exist but, if everything goes according to plan, there’ll be the option of a “European patent with unitary effect”, popularly known as a unitary patent. It will have effect in up to 25 countries – all the European Union states except Croatia, Poland and Spain. Translation requirements will be much less onerous. The cost will be proportionately less.

These reforms will take effect after 13 of those 25 countries, including the UK, Germany and France, have ratified an agreement signed in 2013. In Britain, the necessary secondary legislation has largely completed its passage through parliament.

Inventors will still be able to obtain classic national patents in separate European countries, which they may register in as many countries as they wish. That would still be necessary if they wanted protection in European countries that have not joined the deal. Alternatively, they can obtain single-country patents through national patent offices.

Unified Patent Court

But the most dramatic change of all will be the launch of a Unified Patent Court (UPC). This will have exclusive jurisdiction over disputes about classic European patents as well as the new unitary patents. A single system will make it easier and cheaper for people to protect innovations and enforce patents against most of the EU single market.

All this has been a long time coming, but it was far from easy to achieve. One problem was that different European patent courts have developed different approaches. It’s normal in the UK, France and the Netherlands to try infringement of a patent and its validity at the same time. The Germans dealt with these issues separately, but this so-called bifurcation process is not expected to find favour in future.

It’s hard to see how we could leave the European Union and remain in the Unified Patent Court

As a supranational court, the UPC will become part of the judicial systems of the 25 states that have agreed to join it. However, it will be possible for patentees to opt out of the court’s exclusive jurisdiction during a transitional period. The new court will have some technically qualified judges as well as others who are legally qualified. Recruitment is now under way.

Getting a piece of the action

As far as the UK government is concerned, all this is very welcome, not least because the UK has won a piece of the action. There’ll be a London section for the UPC, based at the new Aldgate Tower on the edge of the City.

We’re not quite at the top of the tree, though. The appeal court and the UPC’s registry will be in Luxembourg. Below that is the court of first instance with a central division as well as regional and local divisions. The central division will be based in Paris, with sections in London and Munich. Paris will have specialist responsibility for electronics and other topics. London will look after pharmaceuticals and life sciences. And Munich will take care of mechanical engineering. All of them will be part of a single multinational court, but national judges will not be required to aspire to grey uniformity as each division is permitted to reflect a degree of couleur locale.

At heart the UPC is an EU court. Like a national court, it must refer requests for preliminary rulings on the interpretation and application of EU law to the Court of Justice of the European Union. So it’s hard to see how we could leave the EU and remain in the UPC.

For now, though, the prospect for companies that seize the moment is a system that will give Europe the edge over the United States. It will have a larger consumer base of more than 400 million people in the 25 countries, and a court with faster and cheaper hearings as well as procedures designed to discourage patent trolls.

It’s not often that a legal affairs writer can get the words “exciting”, “European” and “patents” in the same sentence, but doesn’t that make it an exciting time for European patents?

JUDGING THE BREXIT EFFECT

The agreement setting up a unified patent court is clearly a European Union treaty. Article 84 says that the agreement is open for signature, ratification and accession by any member state of the EU.

The agreement does not say, in terms, that it is not open to non-members or to former members. But that must be implicit.

In March, culture minister Ed Vaizey told parliament that if we left the EU then the UK would no longer be in the Unified Patent Court (UPC). In that event, he thought it would be for the government to decide whether it wanted to rejoin and for the other EU states to decide whether the UK should be allowed back in.

But an opinion from an EU court in 2011 requires the UPC to be part of the EU framework. It follows from this that non-EU states cannot be members.

If the referendum results in a leave vote, the UK would come under pressure to ratify the agreement anyway. That’s because the UPC cannot come into effect until it has been ratified by the three EU states with the largest number of patents. They would include the UK until it formally left.

The unitary patent