It is a ferocious era of development for the car industry. The rise of electric cars and hydrogen fuel cells, and the race to build connected and driverless vehicles, are leading to a transformation in how and when ideas are protected.

General Motors (GM) chief executive Mary Barra predicts the car sector will “change more in the next five to ten years than it has in the last fifty”, and the US Center for Automotive Research says the trade is effectively becoming a software industry.

In such an environment, companies are fervently protecting their intellectual property (IP) and in 2013 the automotive sector rose as high as third in a Thomson Reuters report on patent filing, only trailing IT and telecoms.

Nevertheless, car manufacturers have had to share some of their designs to speed up adoption. Realising they are not the only major players in their industry, they have also begun co-developing with tech specialists.

Going green

The most radical change for car IP has been in green propulsion, either from batteries or hydrogen. This area, the largest for patent filing, is witnessing extensive sharing of ideas.

Two years ago, electric car manufacturer Tesla announced it was making public nearly 200 battery patents, in the face of less than 1 per cent of rivals’ car sales being electric. Founder Elon Musk claimed a need to remove the delay to electric cars’ success.

Toyota, the world’s largest car patent filer, made nearly 6,000 hydrogen fuel cell patents public in early 2015

Opening the patents was a shrewd move. Tesla positioned itself as a top specialist and its revenues will grow with more electric cars on the road.

The company spurred a major response. Last year, Ford opened approximately 650 electric car patents and 1,000 applications, making them available for a fee. The ideas include battery life technology and a system to teach efficient driving.

Both companies are pushing a major opportunity. Tesla, however, is also defending its battery-orientated ideas as Japanese automaker Toyota, with which it had worked, has been moving towards the competing green power source hydrogen.

Seven months after Tesla’s announcement, Toyota, cited by the Thomson Reuters report as the largest car patent filer, made its position clear. It opened up nearly 6,000 hydrogen ideas, for free. The Japanese giant insisted that “unconventional collaboration” would push hydrogen’s growth.

Connected vehicles

Despite the rise of green technology, the continued dominance of petrol-powered cars is creating an awkward patent stance between companies. They are less keen to share ideas based on generations of prior invention.

Manufacturers are under increasing pressure to meet tough emission targets and this has the potential to change their mindset. By 2025 cars in the United States will need a fuel efficiency of 54.5 miles a gallon. The UK is among European nations insisting that from 2050 only zero-emission cars can be sold.

Volkswagen and Mitsubishi famously cheated emissions tests. But across the industry, designs for a genuinely efficient small engine petrol car are high in number.

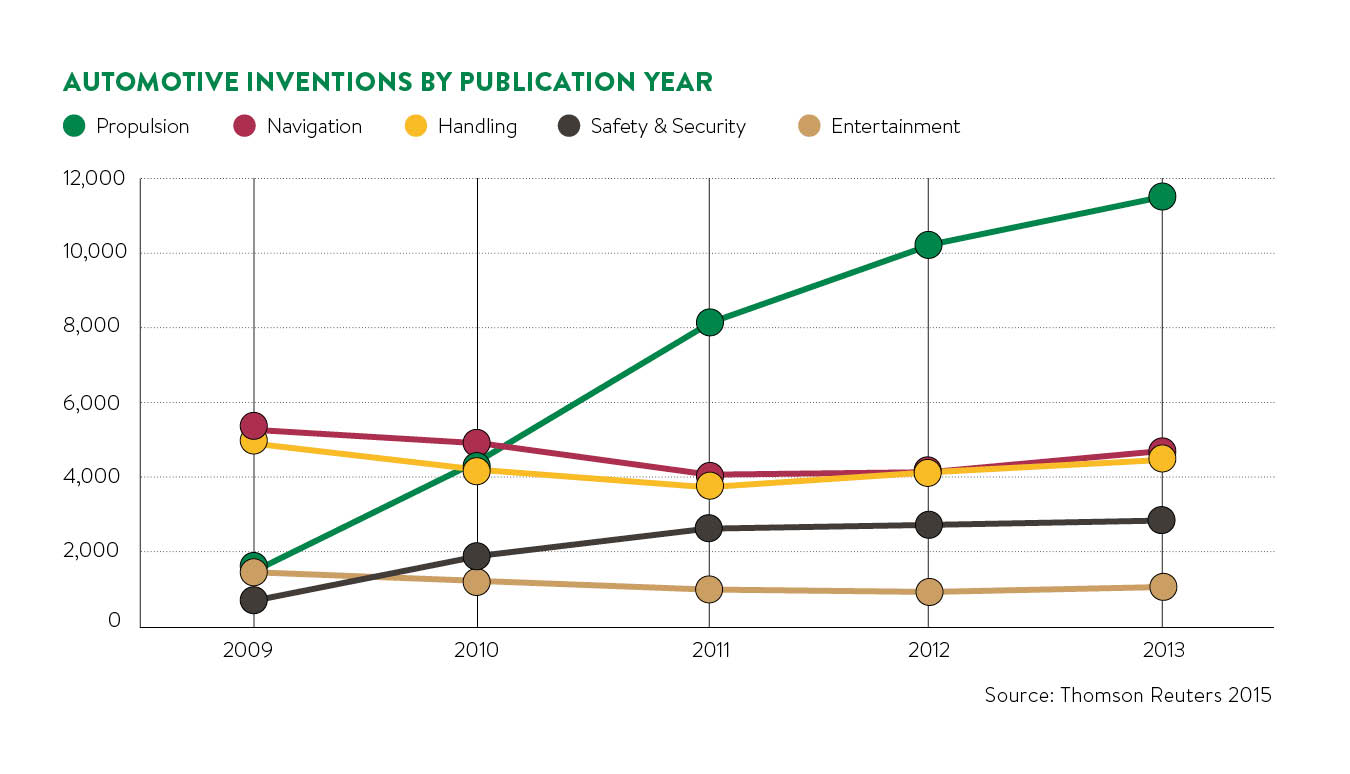

Propulsion patents soared to 12,000 in the five years to 2014, according to Thomson Reuters. In fuel economy, Hyundai was the top patents filer, having grown the most quickly. The number of patents secured by the company was followed by Ford with its much-touted EcoBoost engine. GM and Toyota were next.

The rising interest in connected vehicles is equally spurring more patent applications. GM and Hyundai are particularly active in protecting their designs, and Ford is encouraging employees to build prototypes; last year its staff submitted several thousand inventions for consideration.

Meanwhile, the technology’s complexity is driving a need for collaboration between connected tech experts as its scope spreads from safety to personalisation, shopping, finding restaurants, surfing the web and entertainment. SNS Research estimates that the opportunity for these connected vehicle services will be worth more than £27 billion by the end of the decade.

Connected cars depend on integration with city environments and mobile phones, so system interfaces are being carefully opened up to other companies.

Car manufacturers are increasingly doing deals with telecoms firms around mobile internet, the most urgent feature. There are also tie-ups with technology makers, such as Toyota’s link with Microsoft, a union that aims to connect cars with wearable devices and to interpret drivers’ needs.

Security technology is paramount. There are serious threats to the cars, which are effectively computers carrying passengers, and there are also risks to the mass of data collected from their use. There is sure to be a substantial rise in security designs and patents.

The autonomous car race

But it is with the race to develop autonomous, or self-driving cars, that there is the most rapid patenting. As many as 22,000 inventions of this type were protected in the five years to 2015, Thomson Reuters notes.

Contrary to popular belief, the traditional car manufacturers are protecting far more inventions than their Silicon Valley competitors.

Toyota leads, at 2,000 patents in the five years to 2015. It is followed by industrial technologist Bosch, then Hyundai and Denso, the world’s largest maker of car parts.

GM, in fifth, made the greatest increase in patent filings. This year it also invested $500 million into car sharing firm Lyft, demonstrating where it sees substantial potential.

IT firms are creating impressive software, but are not yet able to mass produce a car. Google, the top such company to feature in the patent list, is back in 26th.

Manufacturers and coders remain dwarfed by the scale of the self-driving mission, and they know they must collaborate

Google recently exhibited a clear sign that it requires manufacturing support, agreeing a deal with Fiat Chrysler for autonomous minivans. The move is expected to be the precursor to similarly clever cars.

Apple, while hotly rumoured to be creating a self-driving car, has not officially partnered with an automotive manufacturer. Tesla is often cited as a potential sidekick, given both companies’ image and abilities.

Manufacturers and coders remain dwarfed by the scale of the self-driving mission, and they know they must collaborate. This requirement is transforming how the industry will turn ideas into a buyable reality.

More broadly, across the many areas of car IP, patent strategies differ enormously. But there is a strong trend towards increased collaboration.

For concepts with less certain uptake, making designs public can fast track development and adoption. The approach of each manufacturer, of course, will depend upon what best motivates customers to buy.