Interconnectivity changes things. You can control the temperature in your house while sitting in an airport. Your car can update the maps for its navigation system while sitting in your garage. You can monitor the water levels of rivers in Oxfordshire or reservoirs in California from your couch. You can see pollution levels in the biggest cities in China or Europe on your smartphone.

This opens up the possibility of interconnecting just about anything, from the very simple to the very complex, to offer remote control, monitoring and sensing

These are all examples of what can be done with the internet of things or IoT – the network of interconnected physical devices such as sensors and actuators in cars, oil pipes, meters, buildings and other infrastructure, linked to the internet so they can exchange data to create new ways of understanding and controlling the world.

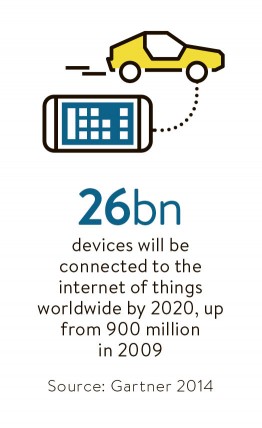

The IoT holds huge promise, according to multiple studies. Research company Gartner says that by 2020 it will comprise 26 billion devices, up from 900 million in 2009. By contrast, there will be about 7.3 billion PCs, smartphones and tablets.

“Connectivity will become a standard feature,” says Peter Middleton, research director at Gartner. “This opens up the possibility of interconnecting just about anything, from the very simple to the very complex, to offer remote control, monitoring and sensing.” By 2016, Gartner says, about 43 per cent of large businesses will have implemented IoT in some way.

Birth of the ‘Internet of Things’

The beginnings of today’s widespread use came from work in the late-1990s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which was investigating how devices and sensors could interact and identify themselves using radio-frequency identity (RFID) devices. The British entrepreneur Kevin Ashton, who worked there, says he coined the phrase “internet of things” as the title of a presentation for Procter & Gamble where he was working in 1999.

“Linking the new idea of RFID in P&G’s supply chain to the then red-hot topic of the internet was more than just a good way to get executive attention,” says Mr Ashton. “It summed up an important insight.”

That insight, he says, is: “If we had computers that knew everything there was to know about things, using data they gathered without any help from us, we would be able to track and count everything, and greatly reduce waste and cost. We would know when things needed replacing, repairing or recalling and whether they were fresh or past their best.”

It’s a grand vision, but it could be realised. Gartner reckons the IoT will generate $300 billion in incremental revenue, mainly from services built on top of software, which will run on cheap hardware that might cost a pound, yet be able to run internet services and exchange data.

The key to the IoT’s success is scalability, building on those cheap devices which will also have low-power demands and could remain in place for years. By using well-known free software such as Linux and connecting to the internet, they can quickly create webs of interconnected devices; the only problem then becomes control, comprehension and security.

Some use IoT interchangeably with machine-to-machine or M2M connections. But, explains Tom Rebbeck, who leads the digital economy research practice at the consultancy Analysys Mason, they’re different. “M2M implies closed systems; IoT is more about sharing and opening of data. So M2M might be a smart meter, which only communicates with the utility company, whereas IoT would be something like a smart city system, bringing together weather and transport and event data to give you travel times,” he says.

Key drivers of IoT uptake

Mr Rebbeck names three key drivers of IoT uptake: regulatory measures, such as the European Union mandating installation of smart meters, capable of reporting meter readings over the internet; well-defined use in large businesses, such as monitoring systems ahead of repair, as happens with lifts and street lights; and growing consumer interest with smartphones and apps that connect to thermostats, heating and alarm systems.

Implementations of IoT systems are already widespread. British Gas’s Hive system, which allows remote control of heating and hot water systems, is installed in more than 100,000 households. The utility company bought AlertMe, an IoT maker which powers Hive, for £44 million in February 2015. That points to uses beyond heating, such as security, smoke detection and lighting, among others. Google-owned Nest internet-connected thermostats and smoke alarms are growing in use.

British Gas has also installed one million smart meters in British homes, which show the householder how much energy is being used at any time and send meter readings back via the internet.

What about cyber security?

However, the rush to deploy IoT systems carries risks as well as rewards. Michael Oh, chief technology officer for TSP, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, warns that the biggest-ever known hack – of the US shopping chain Target, in which 40 million debit and credit card numbers, and personal information of 70 million people was stolen – was enabled via the internet of things. The hackers accessed Target’s computer network via the internet-connected HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) systems controlled by an outside contractor.

He says current IoT systems are being built with too little regard for security: “It’s like when the Wright Brothers were building planes – they just threw stuff together and they had accidents, but they learnt. And lessons will be learnt in the next five years.”