Tackling climate change by accelerating the transition to a low carbon economy will secure a future that is smarter, more prosperous and better for people’s health.

But health probably isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when the topic of climate change is raised. Melting ice caps, heat waves and floods? Almost certainly. Ischemic heart disease and vector borne diseases? Probably not.

Yet the impact on human health from a changing climate, as well as the underlying greenhouse gas pollution that drives it, are significant. Indeed, in 2009 the UCL-Lancet Commission on Climate Change warned that changes in our climate presented the “biggest global health threat of the 21st century”.

Such a warning ought to ring alarm bells around government Cabinet tables, in business boardrooms and in community halls. The World Health Organization (WHO), which hosts a conference on health and climate on Wednesday, August 27, in Geneva, has been raising awareness to the threats posed by climate change since 2008. Yet action is lagging. After all, the state of both public and individual health has huge implications for government budgets, economic productivity and social wellbeing.

So what exactly are the health impacts relating to climate change?

According to the latest findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the impact of climate change on health to date has been limited or at least difficult to separate out from other factors. But the IPCC is clear that a warming world exacerbates many of our existing weather and climate-linked health problems.

There is an urgent need and much benefit to be gained from ensuring health issues are integrated into climate and energy-related risk assessments and decision-making

Future impacts identified by the IPCC include increased incidence of death and injury from more frequent and intense extreme weather events, the geographic spread of climate-sensitive vector-borne diseases such as malaria, and more diseases from malnutrition and poor sanitation due to climatic impacts on regional water supply and agricultural production.

The impact of these is unlikely to be trivial. Single extreme weather events, for example, already kill or injure thousands, if not tens of thousands of people each year. Cyclone Nagris claimed nearly 140,000 Burmese lives in 2008. In Europe, a record-breaking heatwave in 2003 was responsible for 80,000 deaths, mainly among the very young and old, and most in just a few short weeks. A similar blistering event killed 50,000 Russians in 2009. Some climate models predict such summers every other year by 2100.

The economic costs that are tied in with human catastrophe can’t be ignored either. A recent European Commission report estimated that under a business-as-usual scenario, where warming reaches 3.5C later this century, 200,000 heat-related deaths could be expected each summer in the EU, at an annual cost of €120 billion. Even in the advanced economies of Europe, this will put a huge strain on health services.

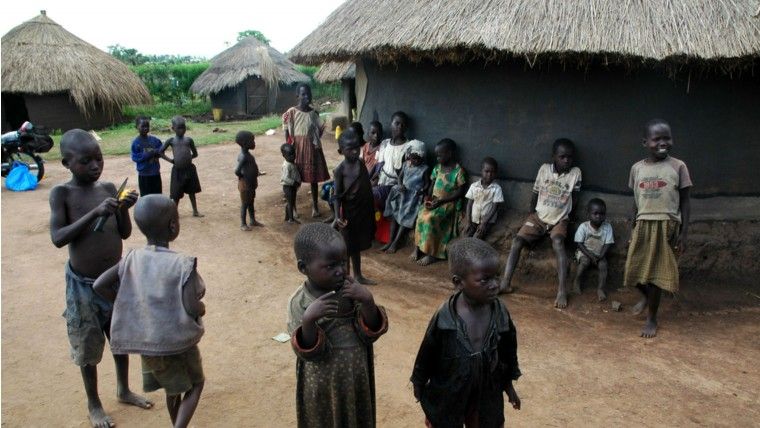

In other parts of the world, the spread of certain diseases will also raise health and economic costs. Malaria, for example, already affects more than 200 million people a year, killing close to 700,000, the majority children. In countries where the disease is endemic and poorly controlled, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, some studies estimate an economic “growth penalty” of 3 per cent GDP a year. Few, if any, developing countries can afford such knocks.

If these are the business-as-usual costs today, then heading off even more damaging impacts in the future is surely an economic, political and risk-management no-brainer. As with other areas of health, preventative action is clearly more cost-effective than a reactive “ambulance-at-the-bottom-of-the-cliff” response, to use an appropriate metaphor.

But there is much more to the climate and heath relationship than simply the avoidance of future health problems and costs.

The reality is that the combustion of carbon-based fuels and the emissions of other greenhouse gases already impose enormous health costs on individuals, businesses and governments. Our reliance on a high carbon, fossil fuel-based economic system is not just threatening our future health, but is making us sick today.

Take air pollution. According to the WHO, microscopic particulate matter from coal-fired power plants, vehicle exhausts and indoor cooking stoves is estimated to cause seven million premature deaths globally a year, manifested mainly through chronic respiratory and heart diseases.

China has provided the most egregious examples of fossil fuel-driven air pollution in recent years. In 2013, the government was forced to effectively shut down Harbin, a city in the north east of 6.7 million people, when the particulate matter index hit 1,000, more than three times the maximum recommended hazard level. Public transport, roads, airports and schools were all shut. A joint study by Chinese and US researchers, meanwhile, has estimated that the severity of air pollution in northern China has taken five years off the average life expectancy of citizens in that part of the country, which includes Beijing.

Of course, China is not alone in facing such problems. A Harvard Medical School study, for example, showed that the use of coal in the US generated an annual health bill of $345-500 billion, exceeding the economic benefits provided in terms of affordable heat and power. In India, analysis by one US economist estimated average life expectancy could be extended by 3.3 years through addressing air pollution. Collectively this would add up to two billion life-years saved.

Health professionals have pointed out that other measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions also deliver important near-term health benefits. Walking or cycling short distances instead of using motorised transport, for example, not only cuts emissions, but improves individual and public health, through increased personal fitness and lower levels of air pollution.

Changes in diet could also deliver important health and climate benefits. High-consumption levels of meat and dairy products, for example, come at the expense of increases in heart disease, cancers and obesity, as well as significant greenhouse gas emissions from ruminant animals such as cattle. Increased demand for land for animal grazing and fodder crops, such as soya, also helps drive deforestation. Encouraging more balanced and healthy diets could do much to address these climate and health challenges simultaneously.

The key message from all this is very simple: there is an urgent need and much benefit to be gained from ensuring health issues are integrated into climate and energy-related risk assessments and decision-making. Failure to do so will come at a cost to effective and efficient policy, economic productivity and, most importantly, the wellbeing and health of citizens around the world.

Damian is Senior Policy Manager in our London office and joined The Climate Group in 2008. Over the past ten years he has worked on range of climate, sustainability and trade issues, including the UN climate negotiations, international aviation climate policy and a variety of other issues including climate finance and illegal logging.

From September 22 to 28, The Climate Group will be hosting Climate Week NYC, a key international platform for governments, businesses and civil society to collaborate on low carbon leadership. Please visit ClimateWeekNYC.org for further details and follow #CWNYC for Twitter updates.