The easiest part of the journey is giving young children experience of motor racing, as this can be done at a local kart track. However, as they race through the ranks on the road to F1 they face a bewildering range of options. One of the hurdles drivers face is deciding the best route to choose. For every F1 seat available, a number of potential drivers will be competing for it, each with different backgrounds and experience.

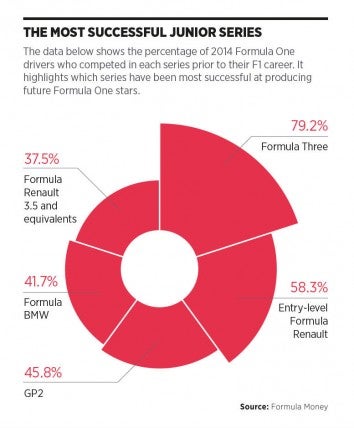

Some championships have more of an impact than others in getting drivers a place in the top tier. At the top of the list is the Formula 3 category, in which 79.2 per cent of last year’s F1 line up have previously competed. This is followed by entry-level Formula Renault, where 58.3 per cent of F1 drivers have raced, and F1’s official feeder series, GP2, at 48.5 per cent.

The remaining two series are tied to manufacturers and make use of similar car designs to highlight each championship’s most talented drivers. They are Formula BMW, which was a training ground for 41.7 per cent of last year’s F1 incumbent, and Formula Renault 3.5, part of the World Series by Renault, at 37.5 per cent.

Starting their F1 journey

This year, five young drivers began their first full season in F1 as they graduated to racing’s top rung, bringing their own tales of success and uncertainty from the depths of junior competition. It cost them dearly.

Toto Wolff, team principal of F1 championship leaders Mercedes, is an expert at steering drivers into the sport. Mercedes has an option on last year’s European Formula 3 championship winner Esteban Ocon. The team’s reserve driver, Germany’s Pascal Wehrlein, also came through F3.

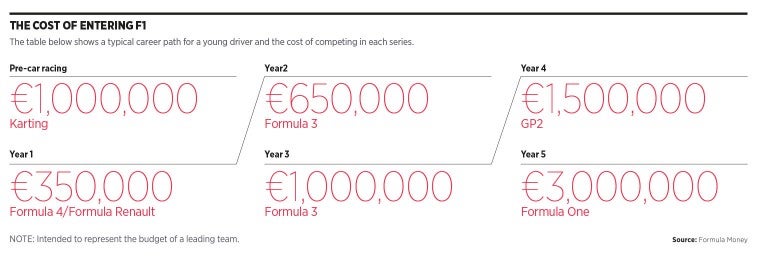

“If somebody is talented, very talented, you probably need to spend €1 million in karting through junior, senior and international races,” says Wolff. “You need at least a season in F4 or Formula Renault which is another €350,000 if you do it properly. You need €650,000 for an F3 season so we are at €2 million. You probably need another season of F3 so you are at €2.6 million or €2.7 million and then you haven’t done any GP2 or World Series. So let’s say you are at €3 million if you are an extraordinary talent.

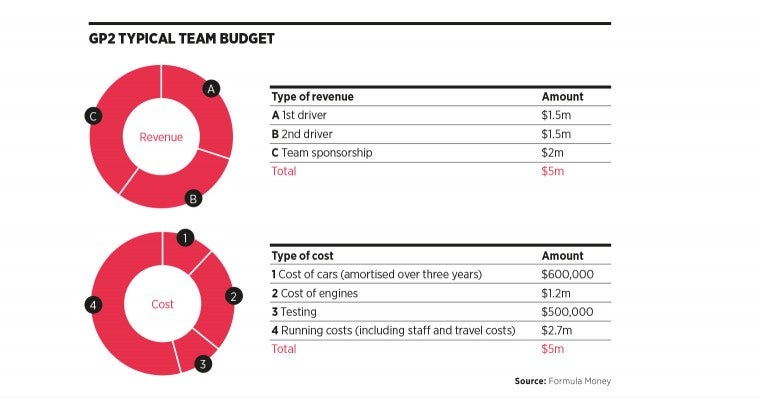

“GP2 is another €1.5 million so probably, if you want to be on the safe side, you are around €4.5 million and €5 million and you have only done one year of GP2. You are on the verge of getting into Formula One but you are not in there. You need another €2 million to €3 million to get the drive. So you are talking about €7 million to €8 million so let’s call it $8 million.”

F1 training schemes for talented young drivers

Wolff explains that, “it’s not possible to bring that cost down because it has become a business so you need to have a sugar daddy or a rich daddy.” One way to reduce the expense is for manufacturers to appoint talent spotters who enlist drivers in a training scheme that puts them on track to F1.

Driver development schemes offer young drivers the opportunity to learn under the guidance of a top racing team but obtaining a place is fiercely competitive. It is a route that has proven successful for some of F1’s most recognisable names including Sebastian Vettel, Daniel Ricciardo and Lewis Hamilton.

‘The most sensible route to F1 at the moment is Formula Three. It is a huge grid, almost 40 cars’ - Toto Wolff

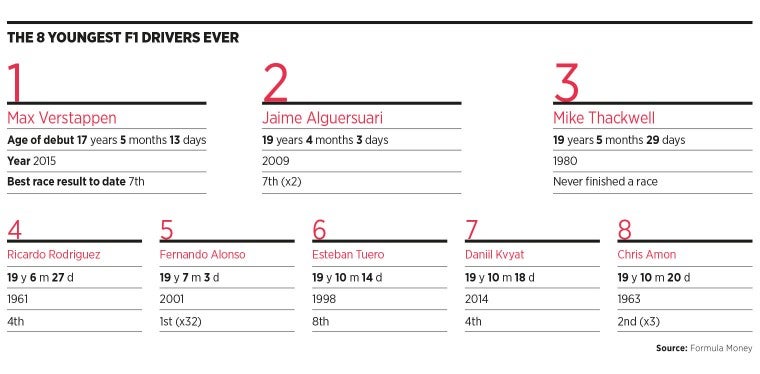

This year the attention falls on 17-year-old Max Verstappen who became the youngest driver in F1 history with a seat at Toro Rosso. Verstappen joined Red Bull’s driver development scheme just two weeks before the announcement of his sudden signing and only one year after graduating from karting. It is a move that is far from the norm.

In contrast, Verstappen’s team-mate Carlos Sainz Jr, who also marks the beginning of an F1 career this year, joins the sport as the reigning Formula Renault 3.5 champion and comes with four years of experience under Red Bull’s supervision. He is among an impressive list of graduates from Renault’s flagship series and joins Sebastian Vettel, Daniel Ricciardo and Kevin Magnussen in the 3.5 litre history books.

Wolff says he is considering reinstating the Mercedes young driver programme, which had its heyday in the 1980s when it nurtured talent including Michael Schumacher and former Williams driver Heinz-Harald Frentzen.

“I’d like to set it up again. The reason why I didn’t until now was that I can’t give them proper access. In Formula One I can’t afford to take risks. I need to have the best guys in the cars and in order to have the best guys they need experience so I will never take somebody who has no experience.”

The brightest talent outside F1 is New Zealand’s Mitch Evans who has a glittering list of accolades to his name despite only turning 21 this year

Working up from Formula 3 to Formula 1

He adds that, “the most sensible route at the moment is Formula Three. It is a huge grid, almost 40 cars. We have seen in the last couple of years, the best ones have come from Formula Three and, at the moment, that is probably the race series I would be looking at the most.

“I have programmes where I can place young drivers and then from then on decide whether I want to give them a chance as a test driver in Formula One, give them test days, which I am doing at the moment with Pascal, and then decide if I identify somebody who is promising to be a superstar. We can then decide whether we want to afford to buy them a seat in Formula One.”

The downside of development schemes is that they do not come cheap and getting one of the limited places still requires luck as well as talent on the part of the driver. Fail to meet targets and your F1 career could be over before it has really begun. It isn’t lost on the top talent in racing.

The brightest talent outside F1 is New Zealand’s Mitch Evans who has a glittering list of accolades to his name despite only turning 21 this year.

Evans took a traditional route into racing by starting in karts in 2001 when he was aged six. Between 2001 and 2007 he won 13 karting titles and showed such promise in his home country that he moved on to international competition. In 2007 he qualified for the World Rotax Finals in Dubai and became its youngest-ever competitor at the age of 13.

A lot of driver development schemes are smoke and mirrors in terms of the drivers paying to be there

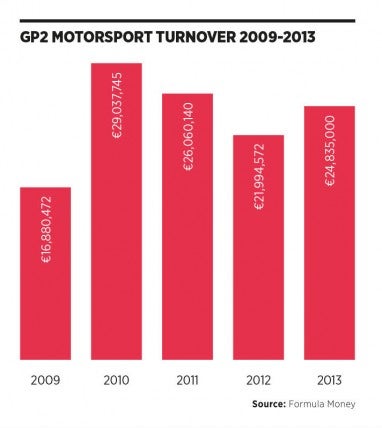

His career accelerated from there as he switched to car racing and competed in several local series in New Zealand and Australia including its renowned Formula Ford Championship. In 2011 Evans left his home country for Europe to race in GP3, the little brother of GP2. The following year he won the GP3 championship and took three victories, six podiums and four pole positions. He has since graduated to GP2 and also competes in the World Endurance Championship (WEC), which is famous for its flagship 24-hour race at Le Mans in France. The tiers of the championship are named after it and Evans’s car is an LMP2, which stands for ‘Le Mans Prototype 2’. Evans finished second in Le Mans this year but F1 has still eluded him.

“I’ve had offers from a number of top teams, including Red Bull and Ferrari, to go on their junior schemes, but I still had to provide some money,” says Evans. “Every driver, whether it’s Carlos, whether it’s Daniel, it doesn’t matter who it is, they still have to bring some money and it is probably more than meets the eye. And those are guys who come from wealthy families so it’s not an issue but I don’t have that option.

F1 driver development schemes not all what they seem

“A lot of driver development schemes are smoke and mirrors in terms of the drivers paying to be there. They are paying through the roof to be there. So a lot of it is just about getting a foot in an F1 team in a roundabout way.”

“There can be benefits if it all goes well but there aren’t many drivers who have come through. There are some like Vettel, Ricciardo, now Carlos and I guess Lewis from the McLaren days. So you benefit but the chances are very slim either way you do it.”

Evans has attracted a collection of sponsors who see the raw racing talent in him. One of his strongest supporters is Colin Giltrap, the most renowned and respected auto industry figure in New Zealand. His company Giltrap Group is one of the largest car dealerships in New Zealand and is the Auckland agent for Volkswagen, Porsche and Bentley. Giltrap is no stranger to racing, having been behind New Zealand’s team in the ill-fated A1 Grand Prix racing series, which featured outfits from different countries.

“If it wasn’t for Colin I wouldn’t be in Europe,” says Evans. “He has been really good to me and a number of other companies from New Zealand then chipped in too. In junior formulae the drivers supply the sponsorship, which is not easy commercially for sponsors from New Zealand. They’re going to get some television coverage but if you’re not an international company it’s hard for them to see the benefit.”

The difficulties of securing sponsorship

The big attraction with Evans is that he is on track for great things and, aside from Giltrap, four other highly credible companies from his home country have stood by him. They are automated accountancy firm BankLink, network solutions provider Mako, butchery chain MadButcher and telecoms company Skinny Mobile.

They believe that partnering with Evans at this early stage will pay off when F1 finally takes note of his achievements. His heritage alone makes him unique, as the last New Zealander who raced in F1 was Mike Thackwell back in 1984.

“My supporters either love their motorsport, they race themselves, or they have a passion for my career,” says Evans. “I don’t have to provide any funding. I’m here to go for the championship, which is great for me because constantly trying to find money is ridiculous and the New Zealand Dollar is two for one so you’ve got to find double the amount.”

However, he adds that coming from New Zealand isn’t always a bonus. “If you are from Australia it is definitely a benefit because commercially it’s a lot better off than New Zealand. We’ve only got four million people so it’s hard for a sponsor that’s not New Zealand-based to see the benefit of it. They would probably rather sponsor someone within Europe. I know that from losing out on a test in an F1 car and also becoming a works driver. I was hampered by my nationality. Technically I probably should have been a reserve driver in F1. Maybe I need to marry a British girl then I might be all right. Money was definitely a factor. I had the grand total of zero Dollars to take with me. I know the guy that got the drive had a budget, a lot of money. The team and the driver himself are from the same country which helped.”

Financial hurdles getting in the way of racing

Former champion Sir Jackie Stewart shares Evans’s frustrations and says, “this whole idea of buying drives business is a very unfortunate thing. And it spirals very negative structures within the sport.”

Another driver who has suffered at its hands is Sam Bird, Britain’s most promising driver outside F1. Like Evans, Bird began his career karting in 2001 and after several years won a scholarship to compete in the inaugural Formula BMW UK championship.

‘My time at Mercedes was great but I couldn’t just sit around doing nothing and be a reserve, I had to be racing something’ - Sam Bird

Rising through the ranks in junior racing series, by 2010 Bird was driving in GP2. Two years later he was driving in the World Series by Renault and in 2014 made the switch to closed cockpit cars with the AF Corse Ferrari team. Bird races with AF Corse in the WEC and also drives for Virgin in the Formula E championship of electric cars.

In 2011 Bird was appointed as a test driver for the Mercedes F1 team and says that a financial hurdle obstructed him from competing in a race. “I was on course for F1 until they told me that I needed to bring millions and millions of pounds,” he says.

Getting drivers to pay to race may seem like a modern concept but is nearly as old as racing itself. Even famed 1950s champion Juan Manuel Fangio supplied funding from the government of Argentina on his way to winning five titles. The trend is still in place today as the Sauber F1 team has hired Brazilian Felipe Nasr who is somewhat of a poster-boy for the sport’s financial culture. The 22-year-old has lured local bank Banco do Brasil to the team giving it an estimated $20 million boost in sponsorship.

Although Nasr has had a respectable junior career, finishing third in GP2 last year, he still epitomises this decidedly unpopular trend of paying to drive.

Paying to drive

Britain’s Will Stevens is also partially funding the resurrected Manor team after its collapse into administration last year under the name Marussia. He is joined by Spaniard Roberto Mehri, who finished third in Formula Renault 3.5 last year while testing for Caterham at three F1 rounds. Stevens too comes from Caterham and raced for the team at the season-ender in Abu Dhabi in 2014.

Getting drivers to pay to race may seem like a modern concept but is nearly as old as racing itself

Like Marussia, Caterham also hit the wall last year and only made it to the final race by raising £2.4 million through crowdfunding. The additional boost from Stevens and his team-mate Kamui Kobayashi amounted to £515,298 but this did not prevent Caterham from closing its doors in February citing the financial strain of competing in F1.

The risks of such a leap of faith were evident with Stevens seemingly putting his 2015 budget and career reputation on the line to compete for a team that could not guarantee a long-term future. In the intricate world of F1, promises are rarely made, as Bird is well aware.

“My time at Mercedes was great but after doing well in GP2 I couldn’t just sit around doing nothing and being a reserve, I had to be racing something. I was actively looking for a race seat, which was never going to happen because I didn’t have the budget.

“We are doing Formula E and I love endurance racing, I think it’s great fun. You look at LMP1 now and they are as quick as Formula One. The budgets are massive, it’s a great career and people enjoy it. I think it’s a great series.”

When it comes to F1, money talks

Whereas the WEC has a reputation for taking drivers based on ability, money talks in F1. It has led to teams taking ever-younger drivers if they bring a big budget with them, and this could change the DNA of the sport.

“For one thing, and this may sound bad, but the cars currently seem to be too easy to drive,” says Sir Jackie. “Almost anybody can go fast in a Formula One car, if it’s a decent Formula One car. Anybody can get in those cars almost immediately and drive them. So therefore there’s something wrong that the engineering has come to a point where too many people can drive them.”

If the cars were tougher to drive then perhaps the best drivers, rather than those with money, would stand more of a chance of making it through. Time will tell whether F1 can turn the trend around.

Starting their F1 journey