Despite all the talk of diversity and inclusion at board level, the easiest way to get to the top is still to go to one of the world’s elite universities.

Harvard tops The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2018 as the world’s most likely educational institution to produce chief executives for a Fortune or FTSE 100 company. Next on the list is the University of Cambridge, followed by Oxford.

Change is happening, but it still has a long way to go

Moreover, a recent study by US academic researchers Jonathan Wai and Heiner Rindermann found that the “old boy network” was alive and kicking. A huge 50 per cent of US leaders in both the commercial and non-commercial sphere went to Ivy League universities compared with a mere 2 to 5 per cent of the country’s total undergraduate population.

But the latest report from the UK’s Sutton Trust on social mobility, entitled Leading People 2016: The Educational Backgrounds of the UK Professional Elite, indicates that things are starting to change, on home soil at least.

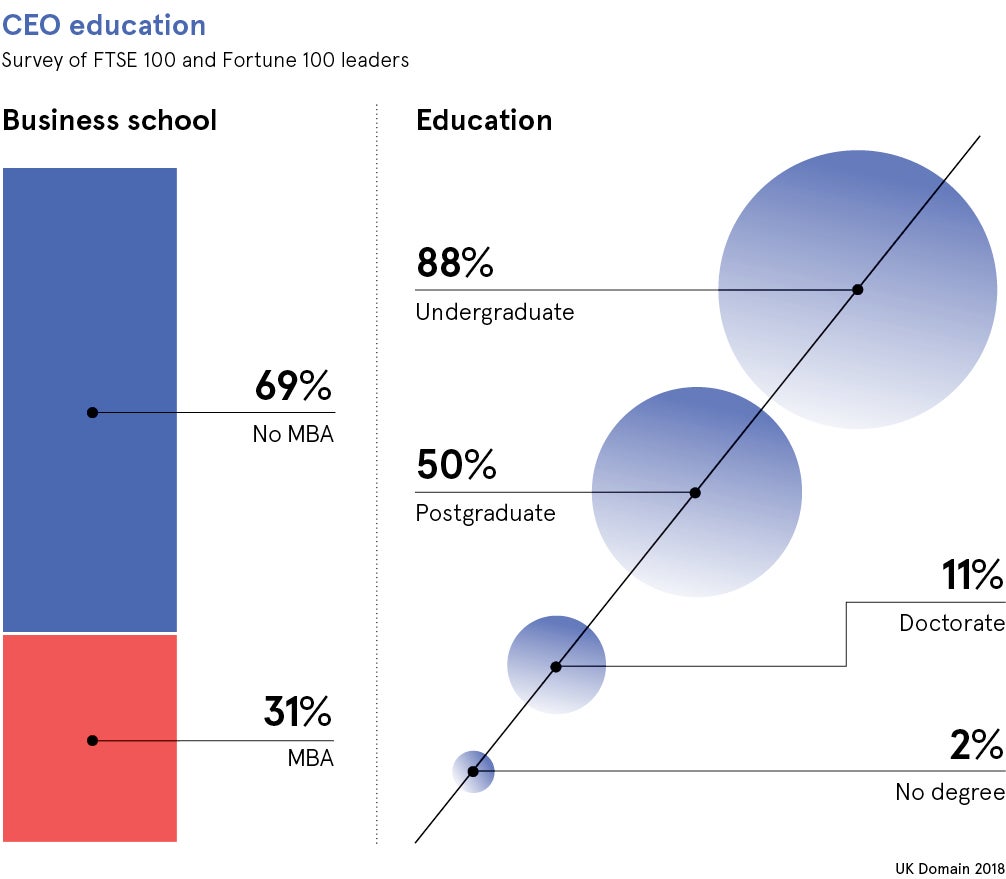

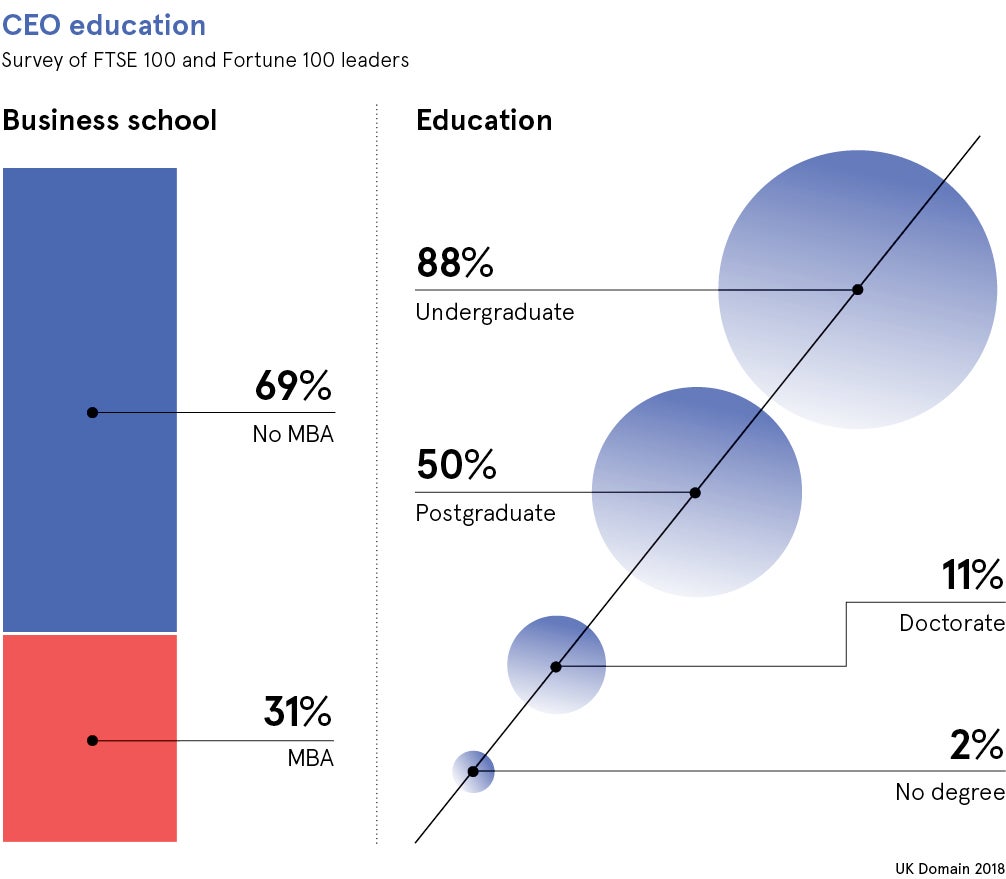

While 70 per cent of FTSE 100 bosses went to Oxbridge in 1987, by 2015 the proportion had dropped to 31 per cent, although because only 1 per cent of the UK population attend these elite places of learning means the number remains disproportionately high.

While many members of the C-suite still find their way to the top via a graduate-entry route that particularly favours Russell Group universities, others have managed to work their way up from the shop floor.

But Paul Modely, director of diversity and inclusion at international recruitment consultancy Alexander Mann Solutions, also points out: “Young people are now starting businesses much earlier, which is moving their careers forward more quickly and creating new pools of candidates.”

Despite the UK’s reputation as a class-ridden society, Mr Modely likewise believes the country is in fact leading the way globally in terms of social mobility.

“The phrase ‘social mobility’ is not one that’s recognised internationally,” he says. “Each country has groups that are underprivileged, underachieving and unemployed, but there seems to be no real movement to address the situation – UK plc appears to be spearheading it.”

Mr Modely first noticed progress about 18 months ago in the wake of various government reviews and anti-discrimination legislation to address such matters as the gender pay gap. A growing recognition of the worldwide shortage of high-quality talent has also played its part.

“The UK’s top 50 organisations, which include the big professional services firms, law firms, banks and government, are all looking at social mobility, and they’re doing well at internal navel-gazing,” he says. “But over the next 12 months, it’ll be really interesting to see how they take things forward.”

Standout organisations include the Bank of England, KPMG and Danish firm LEGO, all of which are particularly progressive in this area.

Stephen Frost, founder and chief executive of diversity and inclusion consultancy Frost Included, believes it is necessary for employers elsewhere to introduce a four-step governance process to promote inclusion. First stages involve gathering and analysing data to help leaders understand the status quo, and thereby recognise what change needs to happen.

Chris Parkes, chief executive of Talking Talent, explains: “You have to do a proper data analysis, so it’s about asking what are the problems in attracting, engaging and retaining talent, and what initiatives do we need to create a stronger, more diverse and less leaky pipeline?”

The next step entails understanding that inclusion is a leadership rather than compliance matter, which requires shifts to take place both within the organisation and, just as importantly, with senior executives themselves.

“The issue is that people tend to reproduce the systems they’re familiar with due to bias, which results in ‘hiring people like you’, and by creating ‘in groups’,” Mr Frost says. “It’s not that people are actively sexist or racist or whatever, they just unconsciously reproduce what they’re familiar with and know to be effective.”

The problem is not only does this situation mean that nothing changes, but it also risks putting off members of minority groups from trying to climb the corporate ladder, ultimately leading to a Catch-22 situation. As a result, the secret to success is to create an inclusive culture that enables everyone to grow and thrive.

“You can put great policies and practices in place, but if people don’t value differences in each other’s backgrounds, it’s not going to be inclusive,” Mr Parkes explains. “In other words, if you take someone from a diverse background and put them in a system that doesn’t respond to them, they’ll just end up getting lost in it.”

Therefore, the final stage of the process involves leaders proactively making a commitment to do something about the situation. On the organisational side of things, this includes setting social mobility targets, and undertaking an end-to-end review of the firm’s recruitment processes and pipeline. It also means putting in place an engagement plan, which includes outreach programmes to target local disadvantaged communities.

But such commitments have a more personal side too. Put another way, it is important that leaders explicitly talk about and model the behaviour they would like to see as others will inevitably follow their example.

Mr Modely concludes: “Many organisations, particularly in retail banking, are talking a good game, but it will take time to really make fundamental shifts. Change is happening, but it still has a long way to go.”