The role of the chief financial officer (CFO), or finance director in old money, is subject to intimidating inflation. Having command of a company’s finances, it seems, is no longer sufficient.

They must also “drive business change”, “influence corporate strategy” as their job “aligns more closely with other C-suite leaders”, according to Robert Half, the recruiters.

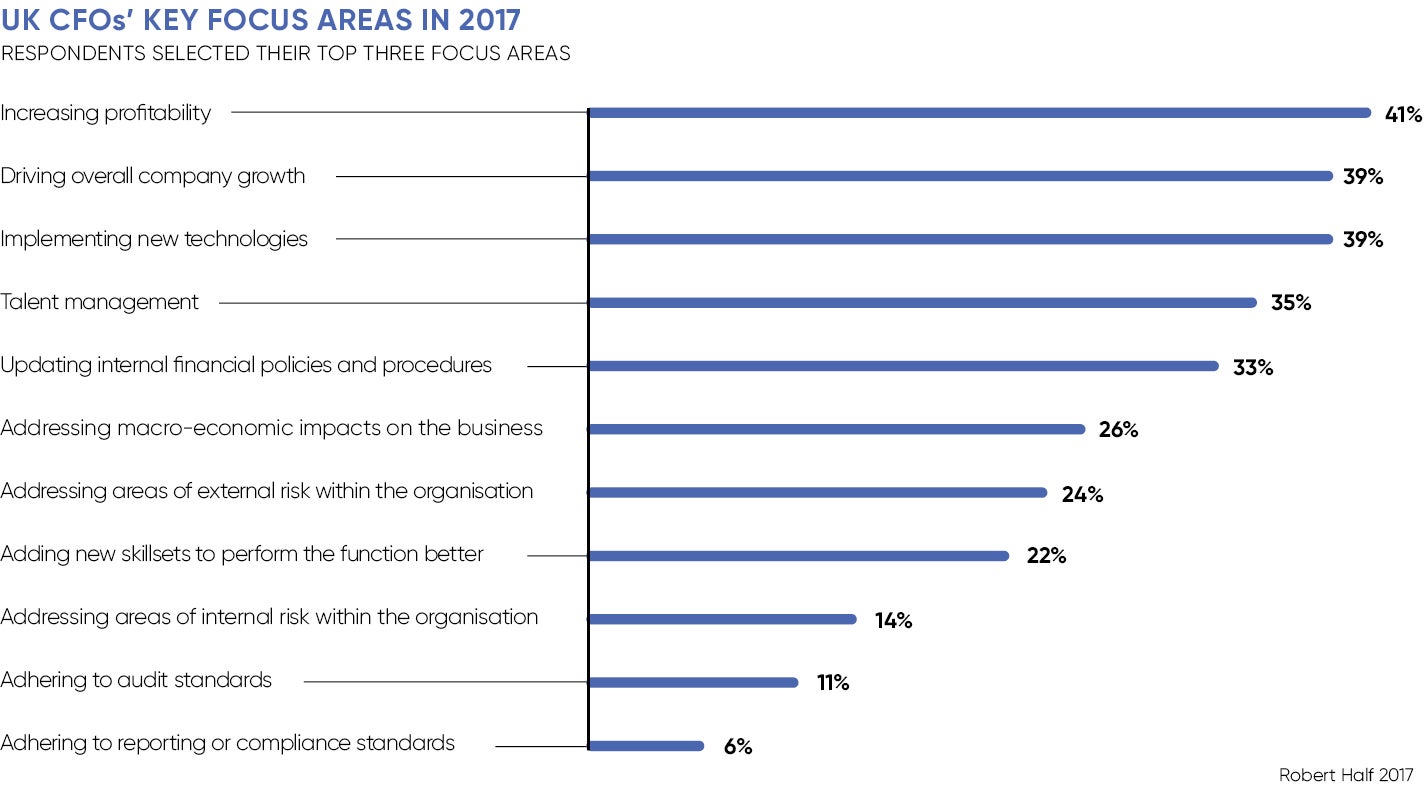

In its recent survey of 200 CFOs, the company found increasing profitability and “driving overall company growth” were the two most common responsibilities being added to their to-do list.

“Business modelling, data analysis and technology will play a crucial part of the CFO role in the future,” says Simon Bittlestone, managing director of Metapraxis, a financial analytics business.

There are undoubtedly benefits in having a more rounded CFO along these lines, but students of companies’ long and dishonourable tendency towards self-delusion will also sense cause for alarm.

A CFO should be a voice of realism and restraint in the boardroom, yet the new vision of their role emphasises only the negative connotations of their traditional reputation as being holders of the purse strings.

As Michael Izza, chief executive of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, puts it: “They can often be seen as a blocker for change if they do not green-light projects of other members of the C-suite.”

The problem is sometimes blocking change is exactly the right thing to do. Now that CFOs are being pulled in new directions, moving towards a more “strategic business partner” role that emphasises closer ties to the chief executive, who will be there to rein in over-ambitious, over-aggressive and hubristic management teams?

In an environment where CFOs are supposed to have twin objectives, growth and financial control, it’s easy to imagine which might win out in the name of pragmatism when, say, a swashbuckling deal is on the line.

Those talking up the benefits of CFOs wearing two hats are failing to recognise the obvious conflicts of interest that are being created as more commercial responsibilities are piled on.

The dangers

There should be no shortage of cautionary tales for what happens when the warnings of the finance function are overlooked or simply when it proved to be the watchdog that didn’t bark.

We need look no further than Royal Bank of Scotland to see what happens when group think infects a boardroom and a rampaging chief executive goes unchecked.

“I think we’re good for it” was Fred Goodwin’s memorable retort when the wisdom of the bank’s disastrous takeover of ABN Amro was questioned at the time. That the bank wasn’t “good for it”, along with the madness of allowing the lender to expand to the point where the value of its loan book was larger than the entire UK economy, offers an extreme example of a neutered risk and finance function.

Students of companies’ long and dishonourable tendency towards self-delusion will sense cause for alarm

The demise of HBOS at the hands of an over-confident management team offers another dramatic case in point.

It’s remarkable, then, that the wisdom of diluting the CFO’s role in the name of commercial expediency is being expounded only a decade on from the start of the global financial crisis.

It has already got to the stage where those who have a more traditional view of the role can struggle to find the best work.

Mr Izza says: “In the case of smaller companies, the CFO can still be limited to the finance function and this might pose challenges. It can be hard to attract the best candidates if they could further their careers by working in a more strategic role elsewhere. Equally, more experienced CFOs may find, while they have expertise in finance, they don’t have the other skills now needed in the modern business world.”

Warwick Hunt, chief operating officer of PwC UK says: “If a CFO now focuses only on their team and the traditional role they played, they’re never going to be credited with adding real value to the wider business.”

An enhanced role where finance directors move “beyond internally focused scorekeeping” to advise on broader trends, including “economic risks and the geopolitical environment”, as Mr Hunt puts it, can of course have its benefits.

But it’s vital that in becoming the co-pilot of the chief executive, CFOs don’t lose their independence and the ability to tell their boss that he’s in danger of stalling.

“As a strategic partner, CFOs need to have the vision to see how projects fit into the business’s overall mission. But they are also about measurement and management, and this means remaining a voice of reason,” concludes Mr Izza.