The Metropolitan Bar in London’s Marylebone is one of JD Wetherspoon’s most iconic venues. Sharing a wall with the Baker Street tube station, the pub is a revamp of the former office of the Metropolitan Railway Company, which was responsible for the world’s first urban underground train line. It’s the kind of “nugget” that Wetherspoon chairman, and self-described “architecture buff” Tim Martin delights in.

Wetherspoon, Martin stresses, may be a chain but it is “fundamentally a chain of ‘local’ pubs… We try to make sure that all our locations preserve and reflect an area’s history.”

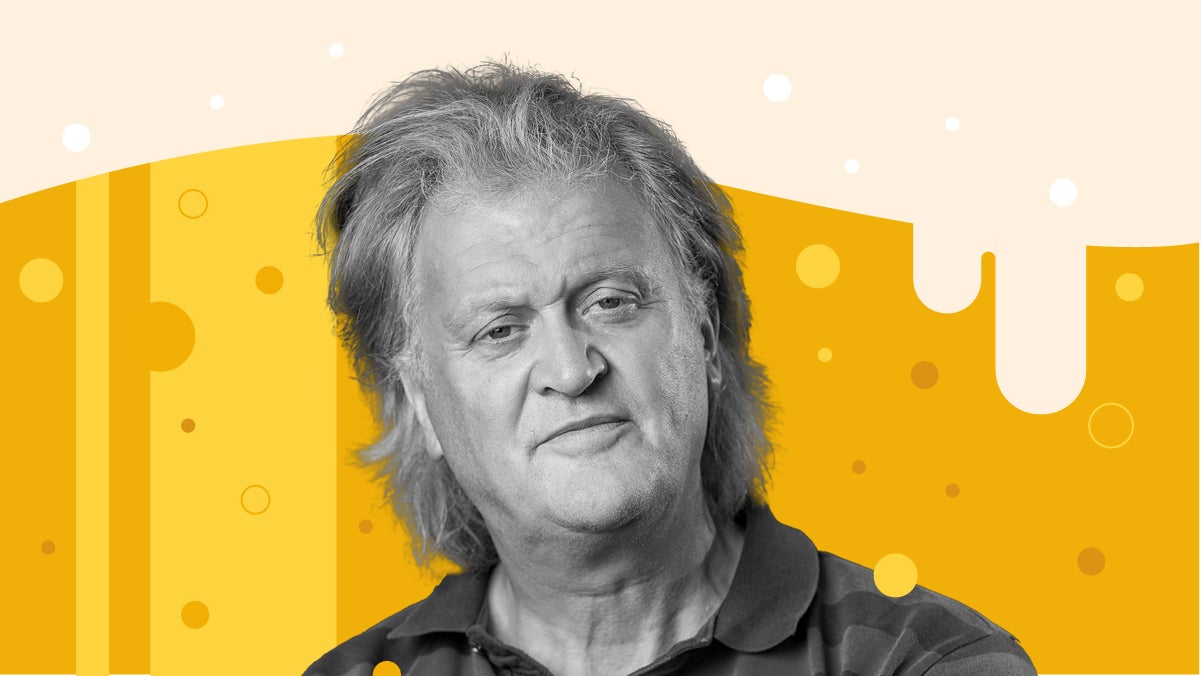

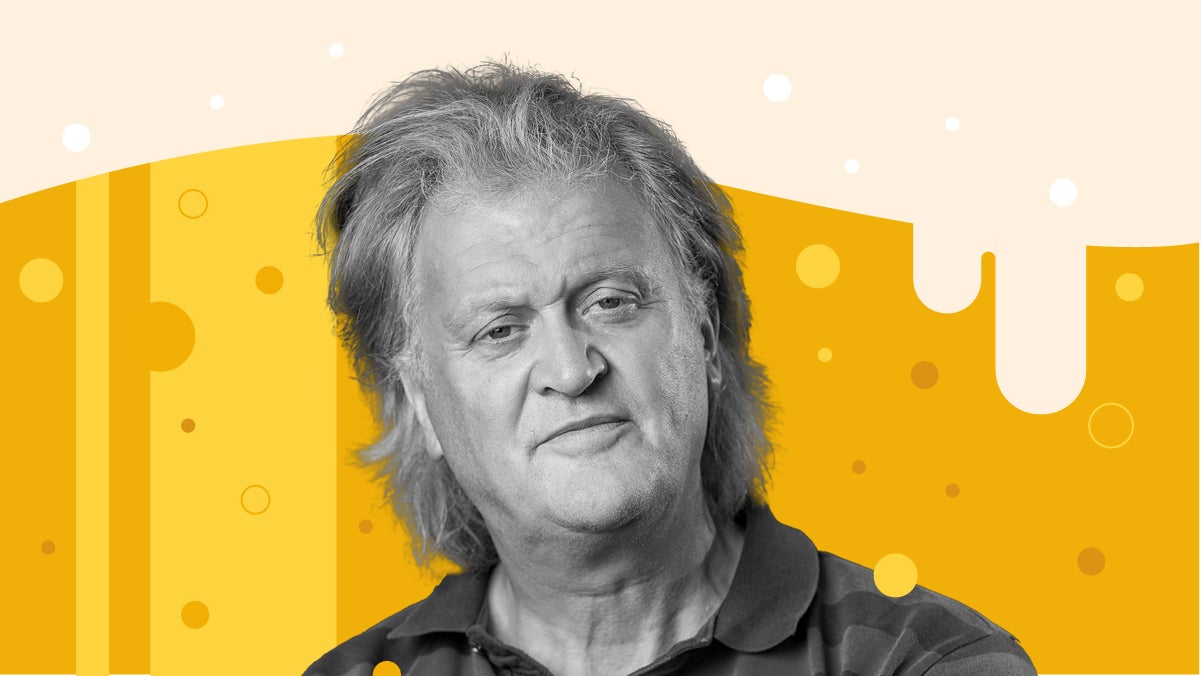

Although Martin’s business is built on a premise of consistency – “I think people like Wetherspoon pubs because of the reliable, known quantities they offer,” he says – there is still a level of individual identity it aims to achieve with each venue. “We’ve always been drawn to buildings with character,” says Martin, who himself sports a unique look.

The qualified barrister, who has never practised law, towers at 6ft 6 ins tall. Seemingly keen to come across as more everyman than executive, he dresses casually, in a polo shirt and jeans.

Why didn’t Wetherspoon pay a dividend?

Like most businesses in the hospitality trade over the past few years, Wetherspoon has hit the buffers. The pandemic and high inflation meant the firm made a loss for three years between 2020 and 2022. But, despite the UK being in the throes of the cost-of-living crisis, Wetherspoon bounced back into the black in 2023, posting a pre-tax profit of £42.6m.

People like Wetherspoon pubs because of the reliable, known quantities they offer

While it would be imprudent to suggest that keeping costs low is the only reason for Wetherspoon’s success – and Martin is particular about the chain being viewed as value for money, rather than cheap – he says it is “common sense” not to price people out of something they enjoy doing.

Owing to the reality of macroeconomics, Wetherspoon has made some job cuts and closed pubs. But it has tried, where possible, Martin says, to pass on these savings to consumers and staff. In April, the company announced a pay rise for its lowest-earning employees.

At the same time, executives’ salaries have been kept under control. No cash bonuses were paid, although they did receive shares under the company’s long-term incentive scheme.

Martin has long beaten the drum for responsible, sustainable and fully costed business. With regard to his decision to resist paying a dividend after the return to profit, he explains: “We had to think about staff first.”

Profit, Martin points out, is not necessarily a panacea. Paying a dividend once and then not being able to pay another one the following year would have been counterintuitive. “You need stability… If you commit to a dividend, it creates an expectation of another one,” he warns. He advises against creating that expectation until a business is “confident of delivering long-term [success]. Right now there are still lots of moving parts. We need to see where the market is first.”

Surveying an empire

The best business leaders, Martin says, are the ones who really understand their trade – at every level. “My business is people,” he notes. “I need to know who’s who and what’s going on.”

Site visits, Martin says, are his favourite part of his job, and that he is far more comfortable behind a bar than in a boardroom. “Oh, I’m very much a publican first and a chairman second,” he says, as if the question were ridiculous.

Martin, who was recently knighted in the New Year’s Honours List, appears an affable, if eccentric, boss. Our meeting is bookended by him catching up with several of The Metropolitan’s bar staff, including a request to meet the two new starters and learn their names.

The power of ‘thank you’

“About 20 or 30 years ago, I read an article by someone from Harvard Business School which said that one of the biggest gripes from employees was a lack of recognition,” Martin reflects.

According to Martin, “one of the most powerful expressions in business is ‘thank you’.” It doesn’t need to be “toe-curlingly obsequious, but if you can spend a couple of days a week going around saying, ‘Nice to meet you, I’m Tim and thank you for your hard work,’ it’s got to be a plus.”

Starting from his family home in Exeter, Martin usually aims to visit 10 to 15 Wetherspoon pubs a week. “A lot of my life is spent between trains and Premier Inn,” he chuckles.

His days often start at 5.30am and are usually punctuated by multiple meetings and phone calls, many of which he takes while walking. “The least I try to do is a few thousand steps a day… As well as the exercise, I think it’s important to get the headspace,” he says.

Wetherspoon without Tim Martin

At 68, Martin is “under no illusions” about his mortality. In the past 20 years, he has had prostate cancer and a burst appendix.

Has he given any thought to Wetherspoon’s succession plan? “I’d be foolish not to,” he cedes. But Martin, who has four children and 10 grandchildren, says his successor won’t be drawn from his family: “I never fancied a dynasty.”

So what is he looking for in a replacement, and how can Wetherspoon the company move away from his personal brand, which is so closely attached to it?

Martin says he hopes to appoint “someone who listens and wouldn’t look to change everything”. Channelling Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart, he believes business leaders should focus on “small improvements over time”, rather than radical reforms, and “learn to love feedback, regardless of whether it’s good or bad, and regardless of who it’s from, whether it’s customers or staff.”

Martin is not resistant to change – “Wetherspoon didn’t serve cappuccinos when it started,” he notes – but he is of the view that change should always be accompanied by choice. Wetherspoon has a smartphone app, which is, he says, “as user-friendly as it could possibly be”, but all of its pubs still also accept cash.

Politics in the pub

As for his own cult following, Martin seems a little embarrassed. Twice, our conversation at The Metropolitan is interrupted by punters wanting to pose for a photograph with him. One congratulates him on Brexit, of which he has been a long-standing and outspoken supporter, while another thanks him profusely for his activism on behalf of the hospitality industry during the pandemic.

Learn to love feedback, regardless of whether it’s good or bad, and regardless of who it’s from

The first punter who asks for a photo whispers “I’m right-wing” as he thanks Martin for obliging, which is met with an awkward smile. Martin does not think there is a typical profile of a Leave voter, less still that Brexit is inherently right-wing.

As a case in point, he highlights that he is pro-immigration – indeed, many of Wetherspoon’s staff are EU nationals, including The Metropolitan’s Portuguese bar manager. He was also in favour of the UK’s remaining in the single market.

Rather, his issues with the EU, he says, are to do with high-cost tariffs and what he perceives as an unnecessary and interfering bureaucracy.

As to whether business leaders should necessarily advertise their politics at all, more recently Martin says he has resolved to try and be “less polemical” in public. He is still a fan of “a good debate”, which he believes to be a key component for any business. It is “healthy”, he says, for colleagues to disagree from time to time.

His desire for Wetherspoon pubs to be accessible and appealing to a wide range of customers, however, outweighs his personal views. The Martin who sanctioned thousands of pro-Brexit beer mats, then, seems to have mellowed.

Great ideas are often simple ones

In the tumult of 2024, few businesses can claim to be thriving. Martin says that Wetherspoon is because of a commitment to some core principles.

Feedback guides any and every future strategy. There is a focus on doing a few things well rather than risking doing a lot badly. And customers, he says, are thought of as people first, rather than numbers on a balance sheet.

Ultimately, Martin acknowledges that he is not everyone’s cup of tea, or pint. But the parable of Wetherspoon is uplifting; you don’t need to like him to drink in one of his pubs, nor will it break the bank.

The Metropolitan Bar in London’s Marylebone is one of JD Wetherspoon’s most iconic venues. Sharing a wall with the Baker Street tube station, the pub is a revamp of the former office of the Metropolitan Railway Company, which was responsible for the world’s first urban underground train line. It’s the kind of “nugget” that Wetherspoon chairman, and self-described “architecture buff” Tim Martin delights in.

Wetherspoon, Martin stresses, may be a chain but it is “fundamentally a chain of ‘local’ pubs… We try to make sure that all our locations preserve and reflect an area’s history.”

Although Martin’s business is built on a premise of consistency – “I think people like Wetherspoon pubs because of the reliable, known quantities they offer,” he says – there is still a level of individual identity it aims to achieve with each venue. “We’ve always been drawn to buildings with character,” says Martin, who himself sports a unique look.