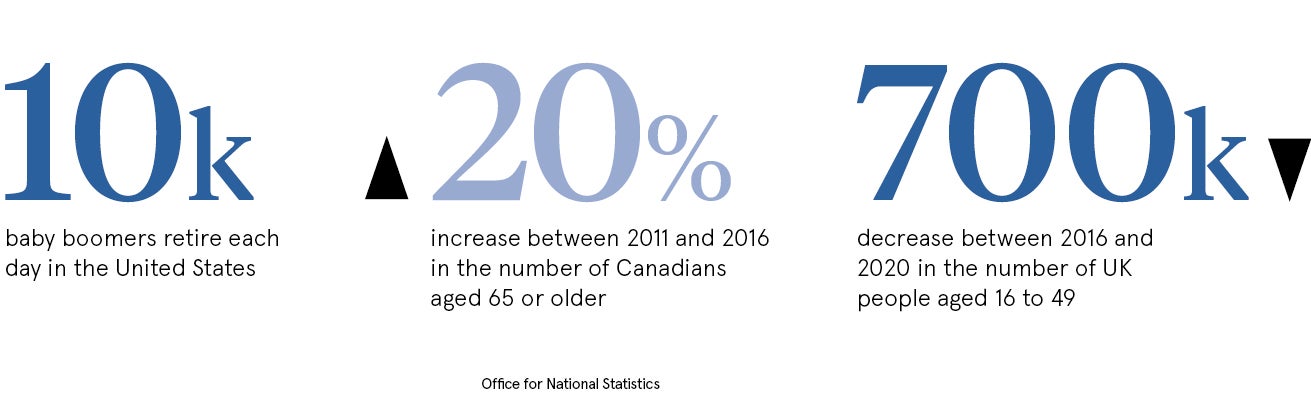

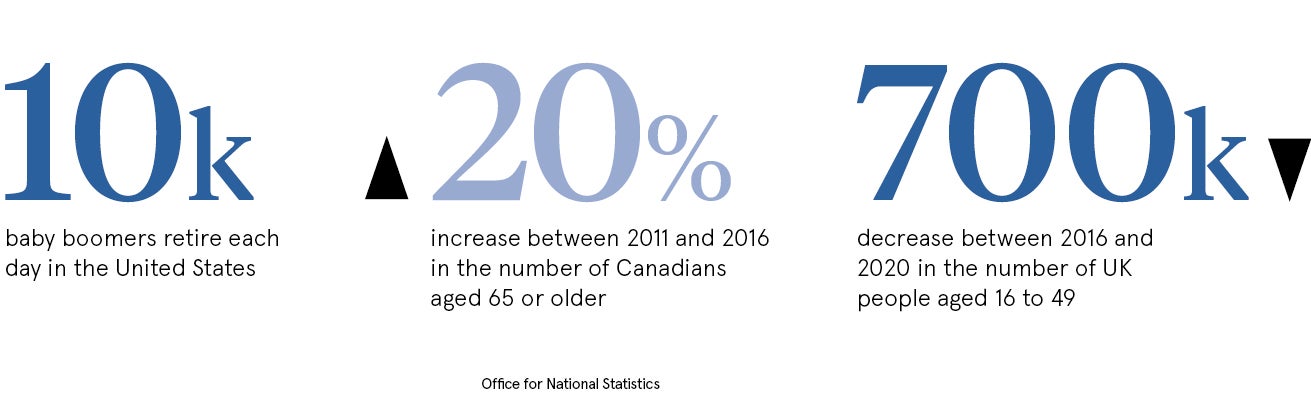

It is estimated that around 10,000 baby boomers retire each day in the United States, while the number of Canadians who are 65 or older grew by 20 per cent between 2011 and 2016.

But North America is not the only place where the retirement of baby boomers – people born between 1946 and 1964 – is starting to leave a void. Although the population in the UK comprised 10.1 million people of between 50 and pensionable age in 2016, this figure is expected to leap to 13.8 million by 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics. The number of those between 16 and 49 years old will, in turn, drop by 700,000.

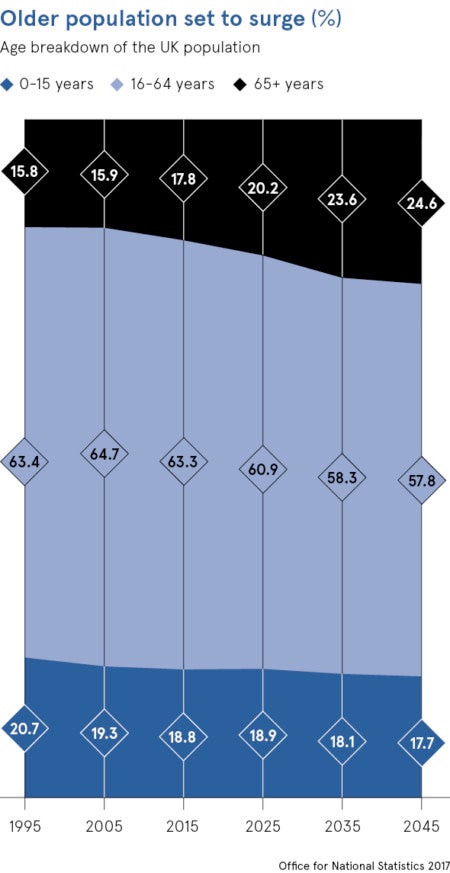

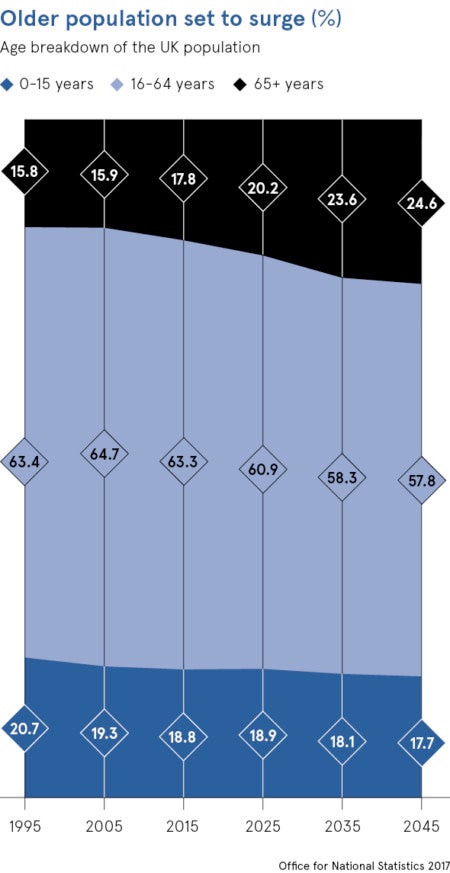

In other words, over the next few years there will be a substantive fall in the size of the country’s current working population of 32 million, with the shortfall only set to increase as baby boomers retire in ever-greater numbers. This situation will inevitably compound a progressively worsening skills crisis across many sectors, but nowhere more than at the senior management level.

Jeremy Tipper, director at talent acquisition and management services provider Alexander Mann Solutions, explains: “It’s going to cause a problem, but it’ll be more acute in certain sectors where the employee base is made up of oversized groups of baby boomers. Major shortages in the medical profession are already appearing and, while it’s slightly less apparent in engineering right now, it’s certainly coming.”

Fields such as IT and the creative industries, which tend to have a younger demographic anyway, will be less affected on the other hand.

So far, the challenge has been somewhat mitigated by increases in the state retirement age and the removal of default retirement, a scenario that will continue to “lessen the blow” as people in future both live and work longer, Mr Tipper says.

But that is not to say employers, particularly in industries that are likely to be hit hard, are unaware of the impending difficulties. While Kevin Davidson, managing director of executive search firm Ducatus Partners, refrains from describing the situation as a catastrophe, he undoubtedly sees it as a problem that needs to be addressed sooner rather than later.

“People in engineering-related sectors have been talking about the demographic time bomb for ever, but it’s still crept up on them and I’m not sure everyone has a real appreciation of what needs to be done just yet,” he says. “Although I can’t see it ending up in crisis, I think companies probably need to do more to try and progress younger generations into leadership positions more rapidly.”

To this end, some employers are, for the first time, starting to conduct open conversations about retirement with people towards the end of their career. Such conversations are often held during annual performance reviews and involve discussing the individual’s aspirations as part of a wider bid to improve workforce planning.

Baby boomers are increasingly being offered flexible working, freelance or consultancy options to dissuade them from retiring altogether

“It’s about asking an individual two or three years out to act as a mentor or buddy in the succession planning process,” Mr Tipper says. “So you identify your middle manager or millennial with potential, but not enough experience, and then provide them with the support they need to take over.”

To both retain their skills and encourage them to undertake knowledge transfer among younger generations, however, these baby boomers are increasingly being offered flexible working, freelance or consultancy options to dissuade them from retiring altogether.

Other employers, meanwhile, are introducing growing numbers of diversity and inclusion policies, and initiatives to broaden their potential talent pool, while also ramping up their talent management activities. They are employing tools ranging from traditional assessments to people analytics software to identify potential high fliers either internally or as part of an external recruitment process.

In sectors such as IT and the creative industries, which are generally younger and rely less on academic knowledge and experience than the medical and engineering worlds, these millennials are then fast-tracked through a management development process and accelerated up the career ladder.

But while this career compression is undoubtedly good news for millennials who are often impatient for promotion, it is leading to a certain amount of disaffection among generation X – people born between 1965 and 1976 – who can feel that youngsters are taking over “their” jobs without needing to put in the years of hard work they have.

As Tom Blower, director of leadership development consultancy Black Isle Europe, concludes: “It’s hard on generation X who are waiting for a tap on the shoulder to say ‘it’s your turn for promotion as you’re next in line’. But if the idea of people potential takes root, which it is in some areas, it’s not necessarily going to be about experience, but about who will be the most effective future leaders in a world undergoing widespread digital disruption.”