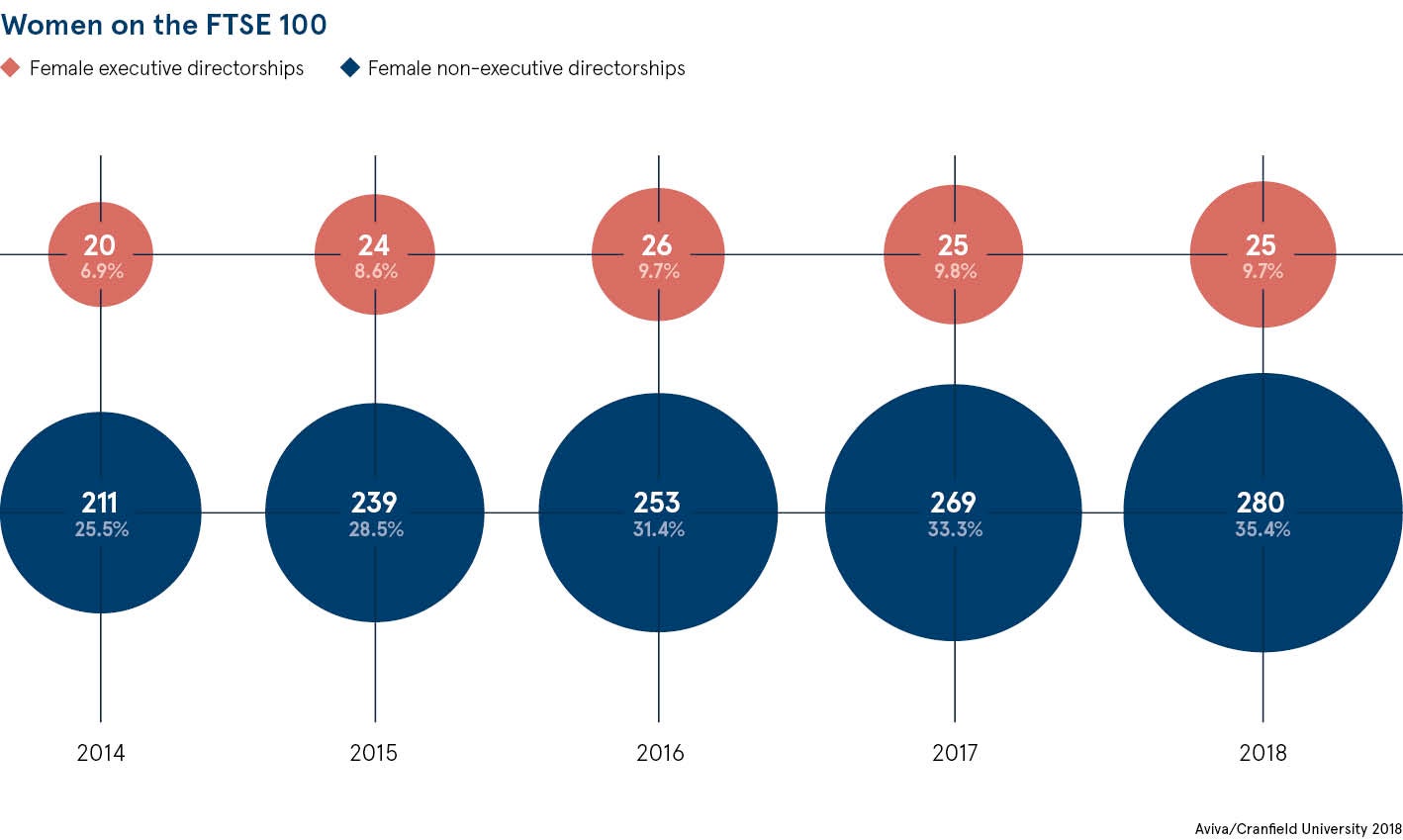

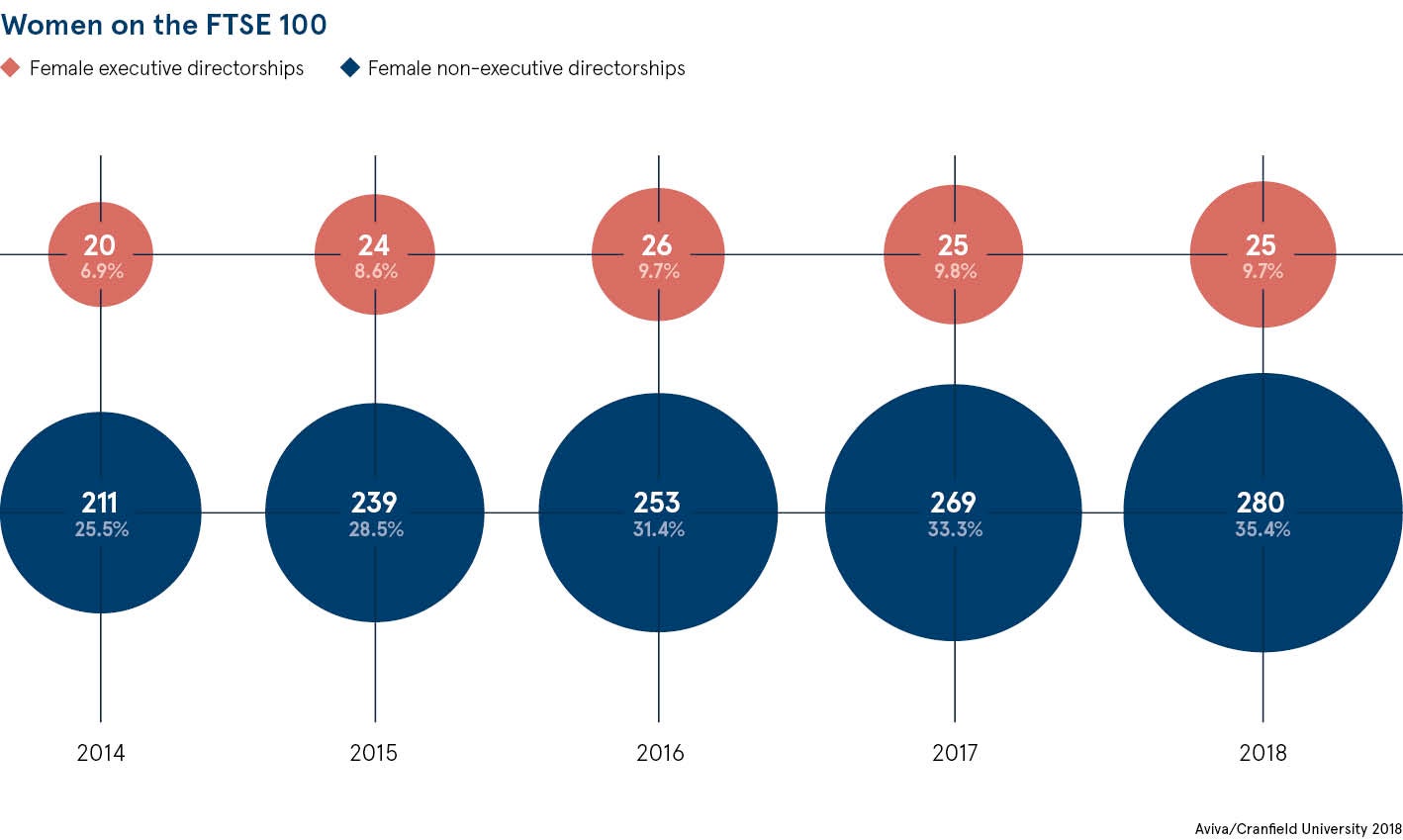

This year the number of women on FTSE 100 boards exceeded 30 per cent for the first time. Although this is a leap from the woeful 12.5 per cent of female board members in 2011, progress has now flatlined and in some cases declined. The number of women in finance at the top table is also slipping despite the same number of men and women training and qualifying as accountants in the UK.

The most recent data suggests that many boards, predominately led by men, are still not adjusting company culture to encourage women to pursue executive careers. They are instead paying lip service to the government’s target of having 33 per cent of female board representation by 2020 by appointing one woman as a non-executive director. The real bellwether of change, however, is the number of women holding executive board positions.

There’s been really good work done on the obvious things, but now we are into the hard yard

Anna Manz, chief financial officer (CFO) of FTSE 100 chemicals company Johnson Matthey, says: “I’m disappointed to see the data. It takes years of effort to create the career pathways and ways of working that ultimately support female CFOs, but what it requires is supporting women to be successful at every stage in the company.”

There are lots of women in finance, just not enough at the top

There are currently just ten female CFOs in the FTSE 100, of whom Ms Manz is one. That’s just four more than in 2010. Among the FTSE 250, the number of women in finance in executive directorships has fallen from 38 to 30, according to the Female FTSE Board Report 2018, which has been studying female representation on FTSE boards since 1999. Of the 30 female executives in the FTSE 250, 19 hold CFO positions, the report published by the Cranfield School of Management shows.

Professor Sue Vinnicombe of Cranfield University, one of the report’s authors, says: “Finance is the one area where loads of women go into it and get qualified, which is a real pathway to the top. But the numbers [of female CFOs] are not increasing.”

The 2018 Hampton-Alexander Review, a government-sponsored analysis of gender balance in UK boardrooms, says if current progress continues at a similar rate, the FTSE 100 will hit its target, but elsewhere a step change is needed.

Why are there so few female CFOs and what can companies do?

So, what is holding back progress? The review suggests a number of reasons could be delaying progress for women in finance, such as investor concerns that women lack City experience, too narrowly drawn recruitment briefs, search firms’ bias or inexperienced senior independent directors, who support the chairperson.

Francesca Lagerberg, global leader of network capabilities at Grant Thornton International, which publishes Women in business: beyond policy to progress, says that unless companies truly embed gender diversity policies into a business’s culture then little will change.

“There’s a range of things coming into play. There are not enough women coming into the funnel. It also suggests some systemic issues: a lack of encouragement or the absence of role models. Behavioural change is hard, but it’s important to recognise that it’s not a done deal,” says Ms Lagerberg.

Setting clear goals and measuring progress, making diversity and inclusion targets part of directors’ pay, showing evidence of commercial gains through gender diversity and investing in unconscious bias training are some of the policies that Grant Thornton’s report highlights as ways companies can ensure gender balance at the top.

Most industry sectors’ average among the FTSE 350 is now above 20 per cent of female board representation with some sectors, such as pharmaceuticals, chemicals and media, above 30 per cent. The worst performing sector, consisting of only two companies, was metals and mining with 18.8 per cent of women on boards.

Changing culture is secret to having more women in finance on the board

Research by Professor Don Webber at Swansea University found that male-dominated business cultures, which failed to provide enough encouragement or support for women while they have and raise children, was a major reason for the lack of female CFOs among FTSE 350.

“Our accounting women suggested two significant reasons for dropping out of the executive pipeline. The first was an unaccommodating business culture. The other that there was no appropriate flexible or part-time work available that enabled [women] to balance the demands of work and family. In contrast, the women who were supported by their employer and partner to work part-time resumed a high-level, full-time career once their children were older,” says Professor Webber.

Ms Manz, a mother of three, says: “There’s been really good work done on the obvious things, but now we are into the hard yard. I think the one thing boards need to do is not just worry about executive level. That’s what they are accountable for, but actually you have to go two levels below that to create and embed the change.”

Studies show that boards need to dispel the sentiment that the drive to encourage more women in finance on board is political correctness. They need to see it as a commercial gain. To achieve this will require understanding business processes from recruitment and promotion to mentoring, and then measuring them. This way executives can see what is changing and why. And only with such data can change be affected. Female CFOs will be critical to this drive for data as figures, after all, are their bread and butter.

There are lots of women in finance, just not enough at the top

Why are there so few female CFOs and what can companies do?