The year 2020 has put unimaginable strain on people’s lives, livelihoods and wellbeing. For every count in the daily roll call of death, there is a long list of people who loved and will grieve for a lost life.

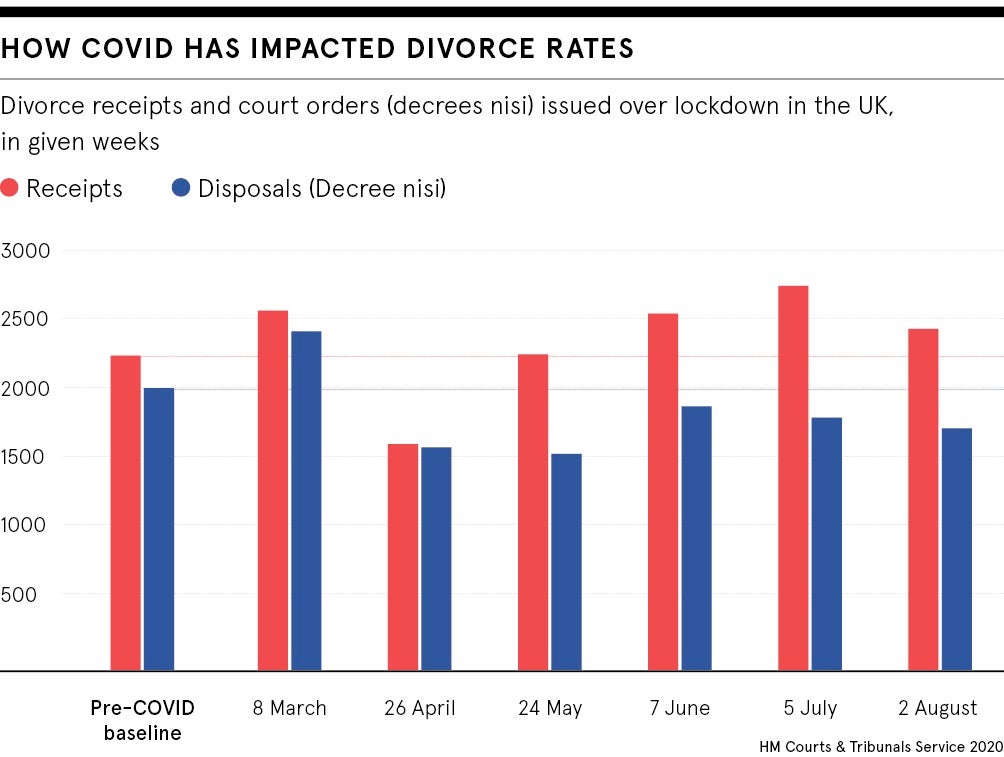

Confinement has acted as a pressure cooker for many relationships. Citizens Advice reported a surge in divorce guidance searches during the first lockdown and new data from the Office for National Statistics shows the largest percentage increase in divorce in nearly 50 years.

Legal services are increasingly required to deal with the most emotionally fraught circumstances by people desperate to get their affairs in order. There has been a rise in legaltech platforms aiming to make sensitive processes, once considered the exclusive domain of family or private client lawyers, more accessible and cost effective.

Dealing with emotionally-charged issues

Coronavirus caused many people to think seriously about their mortality perhaps for the first time. Farewill, the UK’s largest will writer, saw a twelvefold increase in under-35s writing a will at the start of the pandemic.

“Innovative technology can massively help with emotionally charged issues,” says Tom Rogers, Farewill’s co-founder and chief product and technology officer. The online service asks people to fill out a questionnaire and creates a legally binding will for £90 within 15 minutes, half the average UK cost and a fraction of the time typically spent on this difficult document.

Whatever way you cut the numbers, by productivity, growth or earnings, empathetic companies earn more money

Technology can provide a safe distance from having to articulate feelings about death and it enables people to do so in privacy. Arken.legal, an estate planning software provider, has also experienced increased demand this year. Its software automates estate planning documents, such as wills and lasting powers of attorney, by asking people to respond to a questionnaire drawn up by private client solicitors.

March to June was a particularly busy period. Dave Newick, managing director of Arken.legal, says: “Many clients felt helpless in their situation, but gaining peace of mind by organising their affairs was something they could control and be reassured by.”

Building technology with empathy in mind

Belinda Parmar, chief executive of The Empathy Business, advises on how empathy and technology can work together. She says there is considerable evidence that greater empathy leads to increased business profits: “Whatever way you cut the numbers, by productivity, growth or earnings, empathetic companies earn more money.” In a conflict situation like divorce, Parmar believes “people need empathy more than ever”.

Amicable, a digital divorce service, aims to make the process kinder and more affordable. It works with couples to help them agree and draft a divorce settlement that can be taken to a family law judge, using a combination of digitised forms, chatbots and the option of human support to help couples get to that stage.

“The divorce system is severely outdated in the UK,” says Pip Wilson, Amicable’s co-founder. “Many people believe the only way to separate is to hire two divorce lawyers who will represent their individual interests.”

At the beginning of the year, a High Court judgment validated the rights of the company to provide its service without engaging separate family lawyers. Mr Justice Mostyn, in his judgment, said the future of divorcing and separating is likely to involve technology and artificial intelligence (AI).

A thoughtful user experience

The UK’s tech workforce is only 16 per cent female, yet the majority of divorces are instigated by women. This poses questions about who is programming legaltech AI and how can it provide optimal support to people who are potentially very distressed?

Wilson says: “Our chatbot understands emotional readiness. If a person using the chatbot service seems unsure about whether they are ready to separate, then they will be directed to counselling rather than being sold one of our services.” Technology is available around the clock, offering guidance during a time of difficult transition. “If there are any complex questions which need explanation, the bot will book in a free call with one of our divorce coaches for more in-depth support,” she says.

Joanna Goodman, author of Robots in Law: How Artificial Intelligence is Transforming Legal Services, says technology and automation platforms “cannot replace the human side of dispute resolution”. What they can, and must, do is create a “thoughtful user experience”. In the case of chatbots, this would be a process that links a user to a real person, rather than repeating standard responses, to make sure sensitive personal issues can be properly supported and resolved. This is especially important in complex cases.

Digital literacy varies drastically from person to person and the range of end-users must be considered by legaltech providers. Parmar says it is crucial that any company incorporating chatbots makes it very clear if you are talking to a human or an algorithm. Clients may not immediately realise a digital assistant is a program not a person.

When dealing with sensitive matters, empathy and active listening techniques must be replicated online, such as emotional labelling, summarising or mirroring. These could be responses like “Just to make sure I’ve understood” or open questions like “Is this helpful?”.

The future of legaltech

Legaltech intelligence is still in its relative infancy. Many companies have seen the opportunity to provide smoother legal processes and use smart questionnaires to automate complex, often costly documentation traditionally drafted by family lawyers, private client lawyers and estate planners. However, the technology does not compare to the hugely advanced AI used by a human-like robot such as Sophia, the world’s first robot citizen. There is still an essential need for a human expert to interpret the law.

As the public continues to turn to online legal services, one thing is clear: the people behind legaltech programming must ensure it reflects the spectrum of experience of life’s toughest situations. Empathy and understanding must continue to be built into the heart of further developments.

The year 2020 has put unimaginable strain on people’s lives, livelihoods and wellbeing. For every count in the daily roll call of death, there is a long list of people who loved and will grieve for a lost life.

Confinement has acted as a pressure cooker for many relationships. Citizens Advice reported a surge in divorce guidance searches during the first lockdown and new data from the Office for National Statistics shows the largest percentage increase in divorce in nearly 50 years.

Legal services are increasingly required to deal with the most emotionally fraught circumstances by people desperate to get their affairs in order. There has been a rise in legaltech platforms aiming to make sensitive processes, once considered the exclusive domain of family or private client lawyers, more accessible and cost effective.