It was the first known cyberattack on an entire country. On April 27, 2007, the small northern-European state of Estonia came to a standstill. The country was hit by a series of cyberattacks that lasted weeks, targeting the online infrastructures of key Estonian institutions such as banks, government agencies and media outlets.

Cash machines were disabled. Email systems collapsed. Newspapers and broadcasters were unable to communicate.

The likely culprit? The attacks were reportedly carried out via Russian IP addresses and were triggered around the time when the Estonian government moved a Soviet-era statue from the centre of the capital Tallinn to the outskirts. However, there is no firm evidence that Russia was behind the attack.

Cyberspace is already an active battleground, with state and non-state actors continuously searching for adversaries’ vulnerabilities, trying to obtain secret information, developing weapons and occasionally deploying them

Estonia’s crisis was merely a taste of things to come. Another major incident occurred the following year. The United States and Israel were believed to have secretly launched Stuxnet, a malicious computer worm, to sabotage centrifuges at a uranium enrichment plant in Iran. The Iranian authorities didn’t even realise the nuclear plant had been under attack until two years later.

Cyberattacks are becoming more ambitious

Such attacks have become more frequent and ambitious. In 2014, hackers used sophisticated malware to infiltrate the industrial control system of a German steel mill. They prevented operators from shutting down a blast furnace, resulting in massive damage to the facility.

In May 2017, the notorious WannaCry ransomware attack, blamed on North Korea, saw a Trojan virus disrupt information systems used by hospitals, businesses, banks, railways and car manufacturers across 300,000 computers in 150 countries. The virus encrypted and locked computer systems before demanding users pay a ransom to restore their data.

“Cyberspace is already an active battleground, with state and non-state actors continuously searching for adversaries’ vulnerabilities, trying to obtain secret information, developing weapons and occasionally deploying them,” according to a report last October by the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MoD) Global Strategic Trends programme.

The cost of cyberattacks is expected to reach a monumental $2.1 trillion this year and to rise by 15 per cent every year. The major risk, says the MoD, is that “cyberattacks can be used to disable industrial facilities or shut down public services”.

A US National Intelligence Agency report published in January similarly warns: “Both China and Russia now have the capabilities to launch cyberattacks that could at least temporarily disrupt US critical infrastructure such as gas pipelines or power networks.”

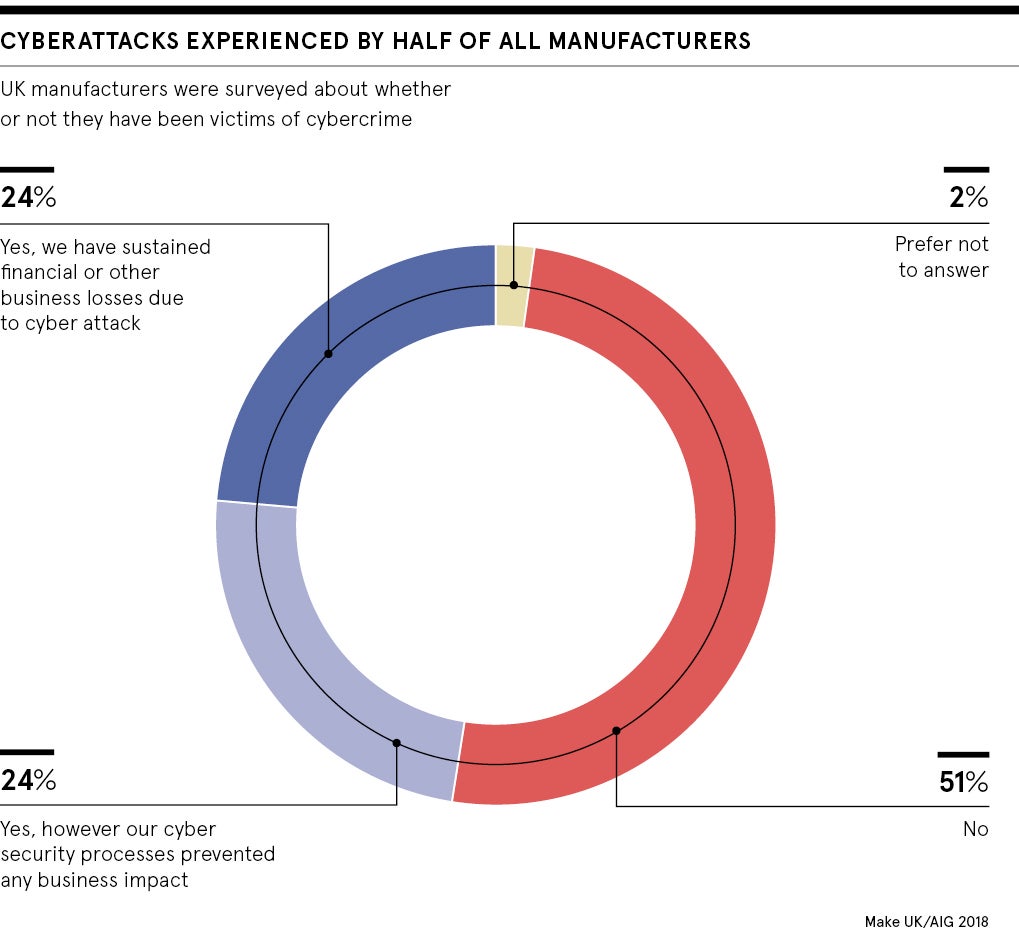

Nearly half of all UK manufacturers have experienced cyberattacks

And manufacturers could end up first in the firing line if a major cyberwar were to erupt. But nation states are far from being the most immediate threats or perpetrators. “Low-level non-state actors can still be reasonably well resourced and cause a lot of damage,” says Corey Milligan, one of the US Army’s first cyber-operations technicians and now a senior threat intelligence analyst at Armor Defense, a cloud security firm in Texas.

“These days cybercrime as a service is thriving. People can be hired through third parties to conduct espionage against rival companies to track disruptive technologies and uncover proprietary manufacturing processes to attempt to reduce their competitive advantages.”

As cybercrime reaches epidemic scales, manufacturers could find themselves sleepwalking into a disaster zone if they do not batten down the hatches.

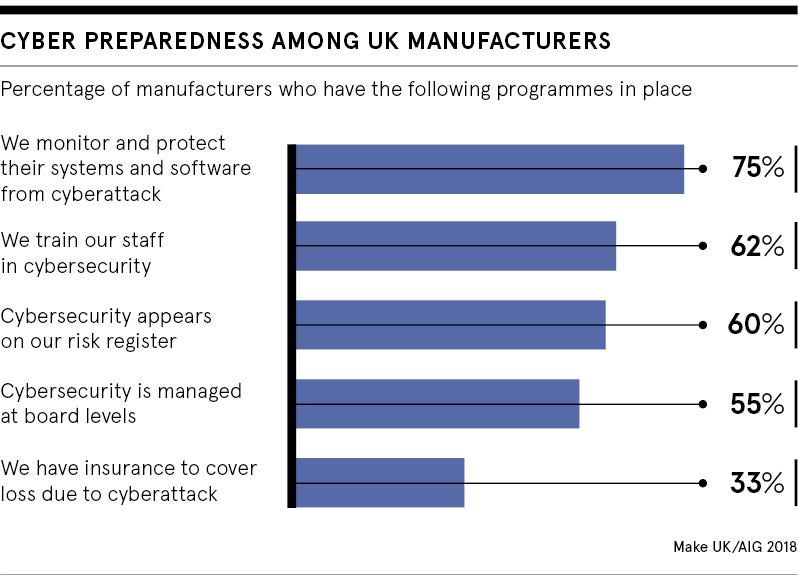

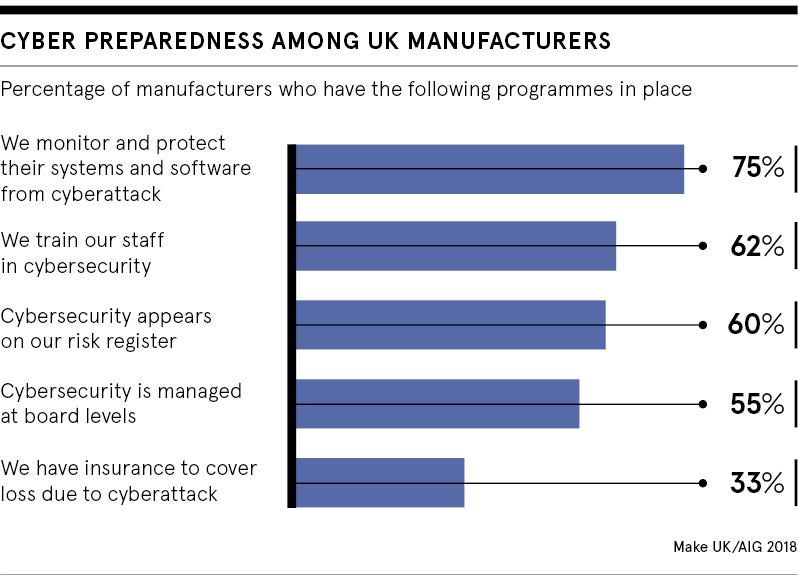

Last April, a report by the UK manufacturers’ association Make UK and insurer AIG found that nearly half of UK manufacturers had been subject to cyberattacks. A quarter of these attacks resulted in financial and business losses. Yet 45 per cent were not confident they had the right tools to protect themselves.

Similarly in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, as many as two thirds of manufacturers said they were affected by cyberattacks over a two-year period, according to Bitkom, losing a total of $50 billion.

Manufacturers need to get wise or the country could suffer

Ironically, manufacturers are often a desirable target due to the sheer complexity of their processes. “Look at critical infrastructure for generation of electricity, water, services and so on. The challenge is in the uniqueness of the devices involved,” says Mr Milligan. “Just to evaluate the risks requires specialised training on how the individual devices work. You then need to go in and do the work of securing the systems. It’s a difficult, expensive and painstaking process.”

But he warns that unless manufacturers get on the case, they will face mounting costs from incoming government regulation; costs which some fear could put the brakes on the progress of the fourth industrial revolution.

But according to Professor Maurice Dawson, director of the Center for Cyber Security at the Illinois Institute of Technology, that could be the least of industry’s problems. In his view, the “hyperconnectivity” between smart robots and the cloud could leave entire sectors vulnerable to large-scale attacks with catastrophic cascading effects. At worse, these could take a chunk out of a country’s GDP.

Tampering with equipment in factories producing food, for instance, could lead to incorrect nutrient levels and unsafe items bypassing proper checks.

“Imagine a large organisation like Monsanto. A determined hacker has the ability to go in and change the makeup of the seed,” says Professor Dawson. “They could make the seed life shorter. If you’re planning for a harvest, the seeds fail. Now we have an issue of a food shortage. Or alternatively, the hacker can insert additives or ingredients to spark allergies or create reactions.”

Cyberattacks can lurk for years before striking

Similar risks potentially impacting whole populations apply across different industries. For instance, essential checks and automated quality controls in vehicle production could be bypassed. Breaks, power-steering, windows, on-board diagnostics could all be altered by recoding their operating instructions, degrading the safety and quality of cars.

In both frightening scenarios, the disruption would not be detected for months before it is too late to avert disastrous consequences impacting hundreds of millions of people.

“Attackers would aim to get inside and establish a foothold without being detected,” says Mr Milligan. “They would monitor what’s going on for months if not years and quietly set up code designed to bring down an entire system at one time. And even then, people might still not realise that the damage is caused by a cyberattack.”

Cyberattacks are becoming more ambitious