It’s the ultimate cocky move. A comparative advert is designed to poach a rival brand’s loyal customers with a direct sales pitch. The rewards are potentially huge. And so are the dangers.

Tesco ran an advert comparing its basket of everyday goods with Sainsbury’s. The claim wound up in the High Court. Last year BT ran three adverts claiming its fibre internet offered better gaming and smoother video calling than Sky Broadband. The Advertising Standards Authority booted that one into touch.

But it is possible to pull it off. This year an up-and-coming challenger in the data-integration industry has run a particularly punchy campaign. The extra spice is that both the challenger and the target were founded by the same man.

Gaurav Dhillon founded Informatica in the nineties. It’s now a respected multinational, listed on the Nasdaq and with a billion dollars in revenue. In 2009 he fell out with his firm and quit to found a rival venture called SnapLogic.

Earlier this year, Mr Dhillon prepared an assault on his old firm. With $136 million in venture capital funding, he was so confident in his new company that he authorised the aggressive slogan: “We Left Informatica. Now You Can, Too”. A white paper explained the differences between the two companies. He then unleashed a “rolling thunder” campaign to target Informatica customers.

An e-mail campaign landed messages in the inboxes of executives of key accounts. This was supported by a LinkedIn campaign focused on key individuals. There were webcasts, direct calls to potential customers by the sales teams and a social media campaign. Scott Behles of SnapLogic reports: “Just five weeks in, the campaign has been a resounding success.”

The law

This direct approach is a rarity. Lots of brands think about going head-to-head with a rival. But the risk of a nasty dispute with a rival is unappealing. And there’s the issue of the legality.

The principle is fine in law. The EU directive 2006/114/EC allows use of another’s trade mark so long as it meets basic requirements. There’s an easy-to-read version produced by the Committee of Advertising Practice. Naturally, there are a few caveats. The advertisement must not mislead the consumer. It must fairly compare like for like. And the origin and purpose of the ad must be absolutely clear

It’s also forbidden to denigrate a rival’s trademark. However, references are permitted. O2 sued Hutchison 3G over use of bubble imagery in comparative advertising. Hutchison 3G won, with the judge stating such usage is permitted, providing the comparison is objective and not misleading.

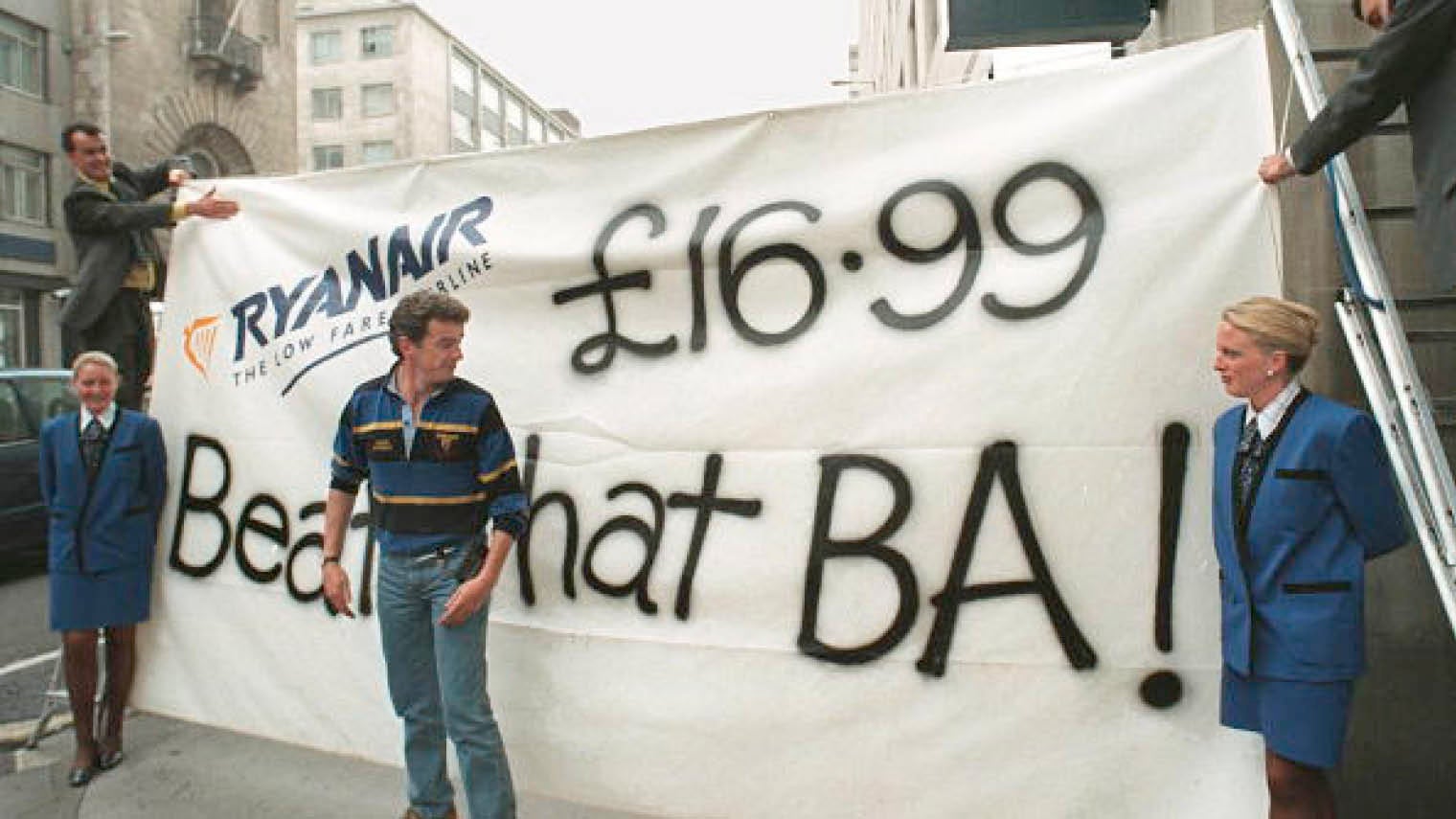

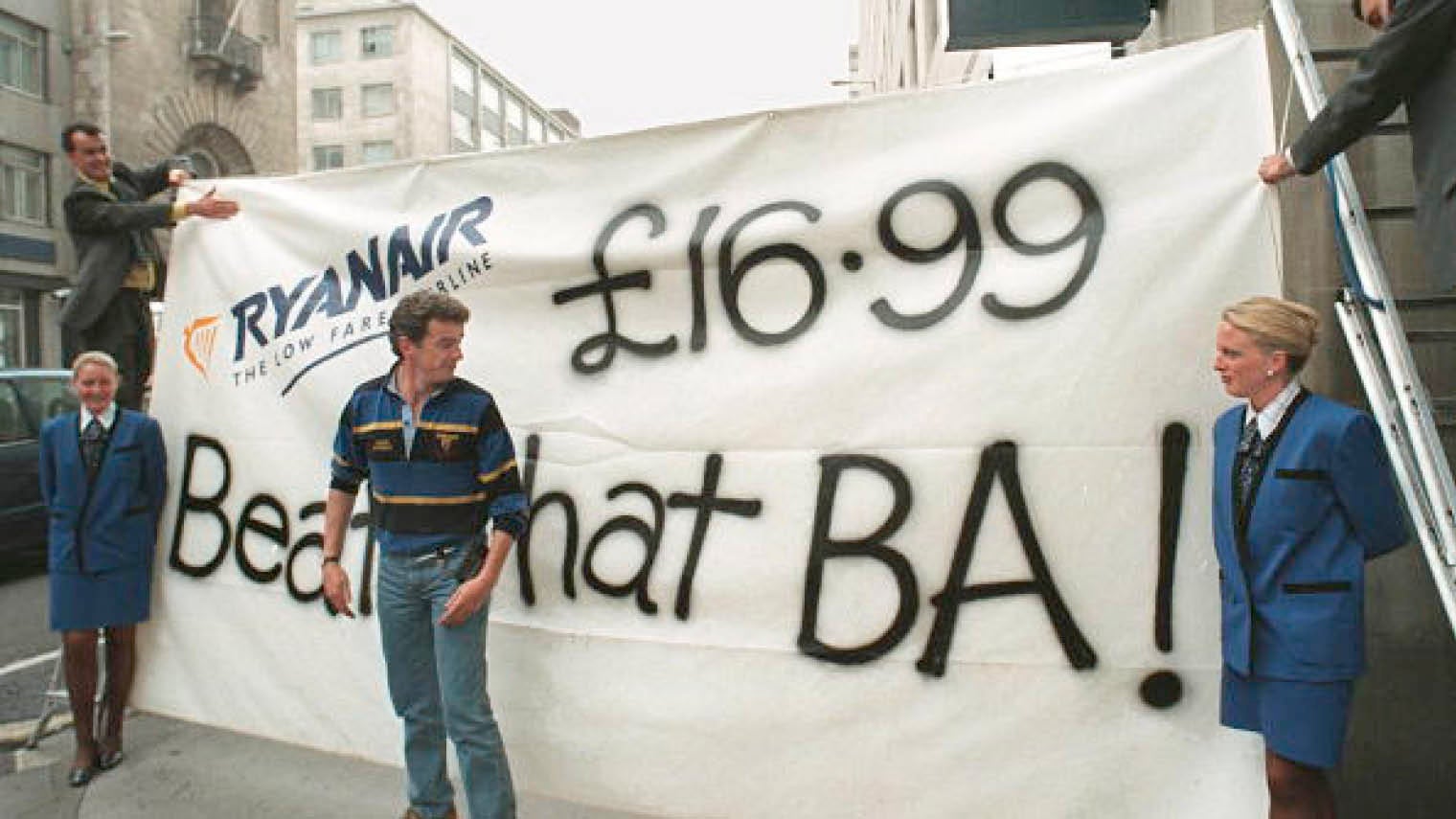

Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary loves poking fun at rivals in ads. His targets were less amused. British Airways took Ryanair to court over a campaign labelling them “Expensive Ba****ds!” But the judge ruled in Ryanair’s favour. His summary described Ryanair’s advert as “honest comparative advertising”.

There’s also the question of efficacy. Does the technique work?

In 2013, two researchers at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Business found good reason to doubt it. Jingjing Ma and Neal J. Roese conducted a series of experiments looking at claims for “best-ever” products. They asked two groups to review deals in mortgages, pay packages and so on. The first group were told to find the best deals. The second group merely looked for differences. The participants were then asked to pick a snack. Half got the one they chose. Half got a substitute. They then rated their snacks.

The academics observed: “The students who had been primed for the maximising mindset and then denied their choice of snack expressed significantly more dissatisfaction than people in the other group; this in turn reduced the amount they would have been willing to pay for the snack and increased their desire to switch to a different brand.”

Companies should think twice about comparative ads, lest their products fall short in any way

The implication is that ads which claim a product is superior to the competition can backfire. Customers become hyper-sensitive to quality claims, and increase complaints and returns. The academics concluded: “For marketing managers, this research provides clear guidance regarding advertising and in-store displays. Companies should think twice about comparative ads and assertions of ‘optimal’ features, lest their products fall short in any way.”

Perhaps the solution is to be subtle. It’s possible to place Google ads to appear next to searches for a rival’s brand.

Offering vouchers can snaffle rival customers. A new browser extension called Pouch brings up vouchers on a checkout page. Thus it is possible to trigger a voucher offer when users are browsing a rival’s site.

For some brands the head-to-head ethos is ideal. They’ll love the rough and tumble, and the devil-may-care reputation. Challenger brands often have little to lose. As Ryanair proved, fortune favours the brave – or cheeky.

Ryanair’s chief executive Michael O’Leary in front of a banner outside rival British Airways’ travel shop in 1998

INSIGHT: TO CHALLENGE OR NOT TO CHALLENGE?

Does it make financial sense to run a comparative ad? Much of it will depend on the loyalty of the newly acquired customers. Eric Fergusson, director of consulting at eCommera, runs the numbers for the likes of Asda, Speedo and Godiva.

He explains how to calculate the value of trying to win a new customer: “The context of retention and repeat custom is very different across retailers. For a seller of beds or boilers it may take five or even ten years before you know if you’ve been successful in earning a repeat customer. While a seller of sandwiches, pints of beer or skin cream should have a clear view in a matter of days or weeks.

“There are some metrics which are equally valid and useful to all. In the instance of some of the longer-term repeat cycles, further creative consideration must be applied. The useful metrics for all businesses are: the lifetime value of the customer; the expected spend of that customer over the next five years or longer; cost of recruitment; order profitability excluding cost of recruitment; and the likelihood of each new customer being retained at each subsequent order point.”

The law