When influencer marketing emerged it was viewed as a breath of fresh air and an empowering movement that provided an authenticity that was in sharp contrast to traditional advertising. However, this sense of authenticity has been eroded by a rush to jump on the influencer gravy train, and a backlash against influencers attempting to blag free goods and services.

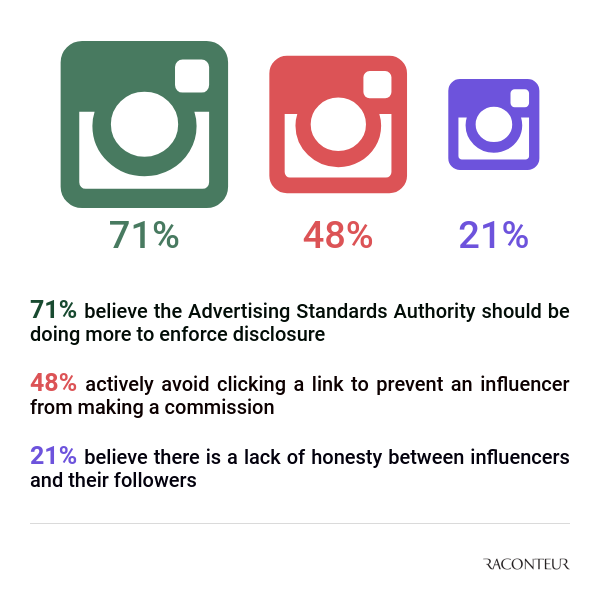

Cynicism of the industry has grown and the Advertising Standards Authority has launched a review because it believes “people shouldn’t have to play the detective to work out if they’re being advertised to”.

Marketers must be wary of cowboy influencers

This is far removed from how the concept of influencer marketing was first born.

“I started my marketing career when social was emerging and it felt like such a breath of fresh air because you had advertising at one end and word of mouth at the other, and it really felt like influencers were at the word-of-mouth end. But I think we have swung too close to advertising,” says Katy Woodrow Hill, strategy director at youth-led creative network Livity.

Emily Austen, founder and chief executive of PR agency Emerge, believes a combination of factors created a wild west-style scenario.

It was a combination of brands not really knowing the market and making it up, and bloggers trying to seize opportunity

“There are a lot of cowboys who are whoring people out for whatever a brand will pay,” says Ms Austen. “Influencers were buying their followers and falsifying their interaction, so the very basis of a financial investment from a brand was on something that was really illegitimate in the first place.

“It was a combination of brands not really knowing the market and making it up, and bloggers trying to seize opportunity.”

Marketers just as guilty as influencers

However, a lot of the responsibility for how the industry has evolved should arguably be borne by the marketers rather than the influencers themselves.

“If you are a young, new talent in the industry, the marketers and brands you deal with have a responsibility to make sure they are being transparent or authentic in their relationships with you,” says Ms Woodrow Hill. “A lot of the time the influencer is vilified, when actually we need to take responsibility as an industry about what we put forward.”

Ms Austen suggests brands can be guilty of encouraging the obscuring of the commercial relationship.

“Having to say it is a paid partnership is quite unattractive for brands because it undermines the legitimacy of the transaction,” she says. “I think that is why people avoid it because the brands have potentially made bloggers feel it is unattractive.”

She believes the public do not break down in their minds the commercial process of a traditional advert such as a billboard, whereas sponsored social media posts are placed under much more scrutiny.

“When you look at someone’s Instagram, you are led to believe it is an insight into their personal life and their choices,” says Ms Austen. “As soon as you overlay something transactional, it makes people feel it is inauthentic because they suddenly question the view you are giving them.”

Positive outlook for the industry

But it need not be all doom and gloom for the influencer industry, which appears to be undergoing some professionalisation.

“We will get more professional engagement with influencers, more proof that they work, more best practice about how they work, so it becomes less of a wild west,” says Ms Woodrow Hill.

The growth of tech tools that enable return on investment (RoI) to be measured is set to root out the inauthentic influencers who are not adding any value.

Ms Austen highlights Dallas-based RewardStyle as an effective means of linking influencer posts directly to retail sales.

A focus on creating collaborative partnerships with influencers is a means of establishing a genuine connection with the audience

A focus on creating collaborative partnerships with influencers is a means of establishing a genuine connection with the audience and weeding out the influencers only in it for the money, according to Ms Woodrow Hill.

“We often bring them in as part of the creative team so they genuinely have some ownership over the idea,” she says. “There is a tendency to see influencers as a media commodity rather than seeing it as a partnership.”

Ms Austen says she would no longer spend any money with reality TV stars on influencer campaigns for her clients because of credibility reasons and the lack of RoI.

Instead she would invest in someone who is “living the life they project” such as a personal trainer who has overcome an eating disorder.

“There has been a separation of the authentic people who are living and experiencing the brands from the other people looking to make a quick buck and dive in,” Ms Austen concludes.

Marketers must be wary of cowboy influencers

Marketers just as guilty as influencers