It was a throwaway comment that led Ronan Shields to break the most important news story of his career. The programmatic editor of US trade publication Adweek was speaking casually to someone at the IAB Tech Lab, a non-profit industry research group in the digital advertising sector.

“They said they had concerns Google would do the same with Chrome as Apple did with its ITP [intelligent tracking prevention] rollout,” he recalls, referring to the 2017 technology that prevented companies from monitoring web users’ browsing behaviour on other companies’ sites in Safari.

“I decided to pursue it. I called up loads of people about it, more so than for any other article I’ve ever written. It was when I realised that Google’s PR teams were starting to get a little bit more nervous than usual about what I was writing that I thought, ‘I’m on to something here’.”

After publishing in March 2019, Shields found himself fielding calls from Wall Street analysts and hedge fund managers, desperate to understand how one decision from Google might upset the entirety of the digital advertising ecosystem. At one point, an investor accused him of fabricating the story for the benefit of a short-seller “To be honest with you, I wouldn’t even know how to short stock,” he says.

It may choke off the economic oxygen from advertising that startups and emerging companies need to survive

But Shields’ story was, in fact, watertight. This January, Google officially confirmed it would be blocking third-party cookies from its Chrome browser by 2022. The week that followed saw stock in retargeting firm Criteo drop to a 52-week low and two industry bodies publicly condemn the tech giant’s move.

“Google’s decision to block third-party cookies in Chrome… may choke off the economic oxygen from advertising that startups and emerging companies need to survive,” wrote the Association of National Advertisers and the American Association of Advertising Agencies in a joint letter.

Months later, marketing after the “cookiepocalypse” is still a topic of conversation at every industry event. Why such a drama over one piece of code?

From context to cookies

The digital advertising world as we know it grew from the third-party cookie, a piece of information that is sent from a website and stored in a user’s browser. First-party cookies are “dropped” by webpage owners when a user visits their own site to save details such as passwords. The third-party kind are used primarily for retargeted advertising.

Cookies are dropped into browsers by webpages and a log of users’ anonymised browsing behaviour is built up and sent back to publishers’ advertising partners. This means advertisers are able to display their ads to the most relevant audience. It’s also the reason the rucksack you debated buying on Asos last week keeps popping up in the middle of that article you’re reading.

Before third-party cookies, brands would choose where to buy ad space through the lens of context. For example, a sportswear retailer would simply choose to display its ads on sites that were read by people who were likely to buy sportswear, such as ESPN or Runner’s World.

“By the late-2000s, advertisers had largely pivoted to focusing on audience, rather than context,” says Cadi Jones, commercial director, Europe, Middle East and Africa, at adtech firm Beeswax. “People had been talking about the promise of one-to-one advertising for so long and suddenly programmatic trading made that dream seem so much more real.

“Now, in the UK, automated trading based on cookie-based audience signals accounts for almost 90 per cent of digital media,” she says.

Making dough from cookie crumbs

That figure, plus the fact Chrome has a 66 per cent share of the browser market, is the reason Google’s decision has caused so much commotion within the ad industry.

Some of the panic is warranted, particularly in the startup sector. Investors aren’t fans of uncertainty and, with the crumbling of third-party cookies coinciding with new privacy regulations in Europe and California, the adtech sector is no longer the sure bet it once was.

“Venture capitalists, who once thought they could help create the next Google if they invested in the right company, just aren’t getting the return they want as quickly as they want,” says Shields. “They’ve lost interest.”

But for the better-funded players, as well as those nimble enough to pivot in the next two years, Google’s decision will not mean the utter “death of digital advertising”, a phrase that’s been bandied about somewhat dramatically in the industry.

For starters, the past five years have seen the digital media landscape diversify to the point where cookie-informed, in-browser advertising isn’t as vital to advertisers as it once was. Cookies, for example, don’t exist with mobile apps or connected TV.

Secondly, many saw Google’s decision coming. Apple’s ITP implementation set a precedent followed by Mozilla’s Firefox, which started blocking third-party cookies by default in June 2019. Meanwhile, the pressure on Google to protect users’ privacy has gradually mounted.

“It would have been unrealistic to not believe that, at some point, this would take place,” says Krystal Olivieri, senior vice president of global data strategy and partnerships at WPP’s media arm GroupM. “We’ve seen different industry groups, technology vendors and adtech vendors try to find solutions that could solve this in advance.

“Most of the clients I’ve spoken to have been quite pragmatic about it. They’re just eager to start thinking about how they will future-proof their advertising investment to make sure the decisions we make right now can set them up for a world post-cookie.”

A new dawn of digital advertising

It’s too soon to tell what that world looks like. Some believe quality publishers will claw back power from the digital duopoly of Google and Facebook, offering premium inventory bolstered by rich subscription data to brands that decide to move back to contextual advertising.

Others predict this will be the nail in the coffin for purely ad-funded publishers, who will no longer be able to draw advertisers a clear picture of their readership.

Some predict a budget shift away from banner and video ads into less targeted forms, such as content marketing.

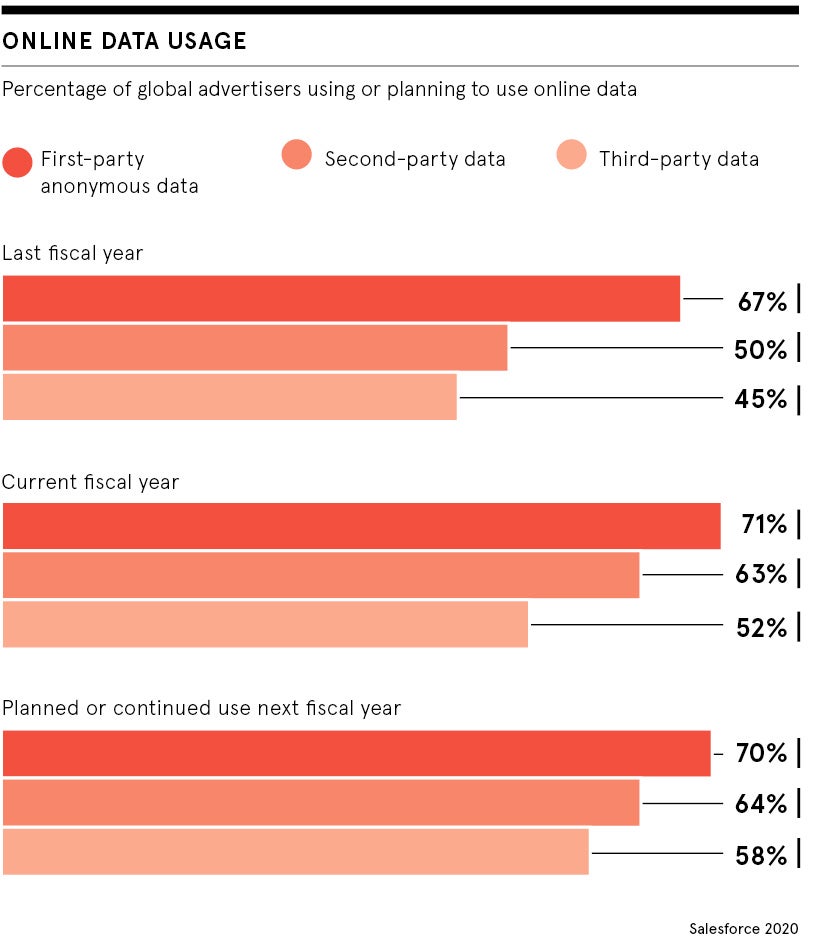

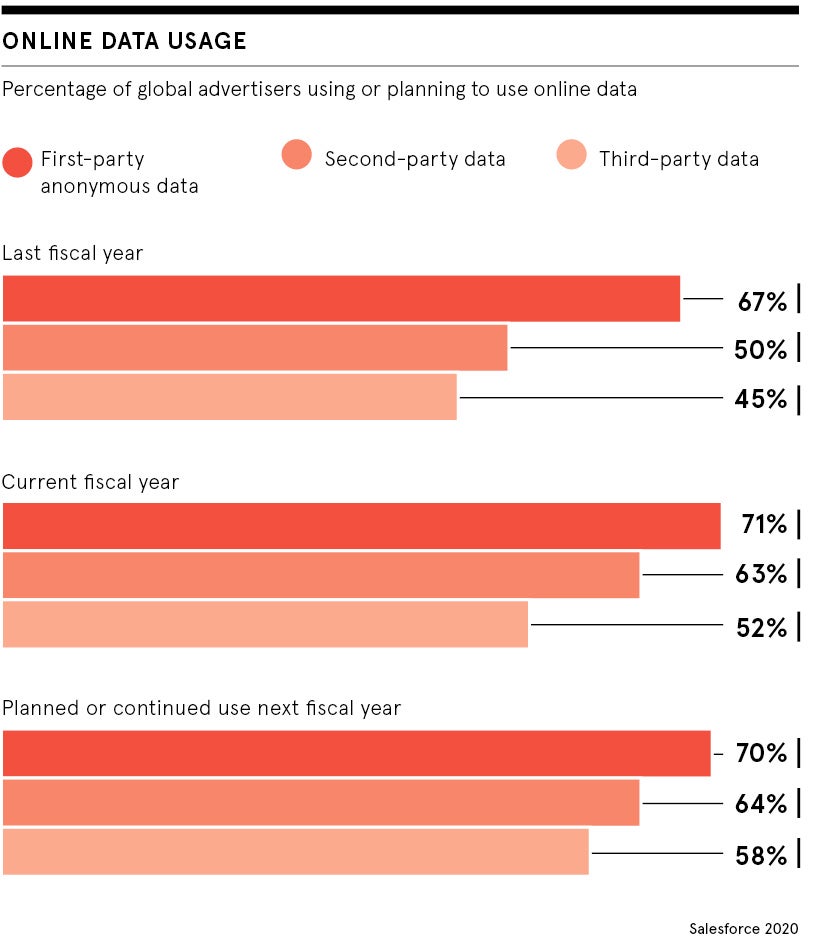

Meanwhile, others watch brands scrambling for their own customer data and believe we’re moving into a world where companies focus less on targeting and more on deepening their relationship with existing consumers. As Olivieri puts it: “In the world we’re moving into without cookies, it will be a challenge if you don’t have first-party data.”

A small minority predict a cull in digital advertising budgets altogether. But that’s a view not shared by Jones. “People are not going to stop spending money on the internet, because ads on the internet are proven to work,” she says. “They’re now thinking about the opportunities, about what it means and how they can make businesses that are going to be successful in the new landscape.”

Olivieri agrees: “I think a lot of people realise we probably stretched the cookie further than it should have gone. They’re optimistic about being able to pivot and focus on potential tactics that may actually deliver greater value than the cookie.”

From context to cookies

Making dough from cookie crumbs