Marketers face a dilemma about mobile. The smartphone has become the primary screen for consumers, so brands have been investing billions of pounds in mobile advertising to reach their target audiences. But because the phone is such an intimate, personal medium also poses a huge challenge as consumers have become increasingly resistant to the growing number of marketing messages they are receiving.

The backlash against intrusive ads has driven a surge in ad-blocking on both desktop computers and mobile in the last 18 months, and forced brands, advertising agencies and telecom firms to reconsider what marketing will work best on mobile.

The media industry’s hope is that a more selective, relevant and personalised approach will appeal to consumers, rather than bombarding them with irrelevant or intrusive messages that slow page-load times and eat up their data allowance.

Mobile advertising continues to grow rapidly. Global revenues almost doubled last year to $53 billion, according to Zenith, a media-buying agency, which forecasts they should more than double again to reach $134 billion in 2018.

Yet the signs are that ad-blocking is still on the rise. “The main trend over the last year has been the shift of ad-blocking from desktop to mobile,” says Robert Franks, managing director of commerce at the mobile phone giant O2 UK. “But adoption of ad-blocking in North America and Europe lags other continents, which is interesting considering high levels of smartphone adoption [in the West].”

Yet the signs are that ad-blocking is still on the rise. “The main trend over the last year has been the shift of ad-blocking from desktop to mobile,” says Robert Franks, managing director of commerce at the mobile phone giant O2 UK. “But adoption of ad-blocking in North America and Europe lags other continents, which is interesting considering high levels of smartphone adoption [in the West].”

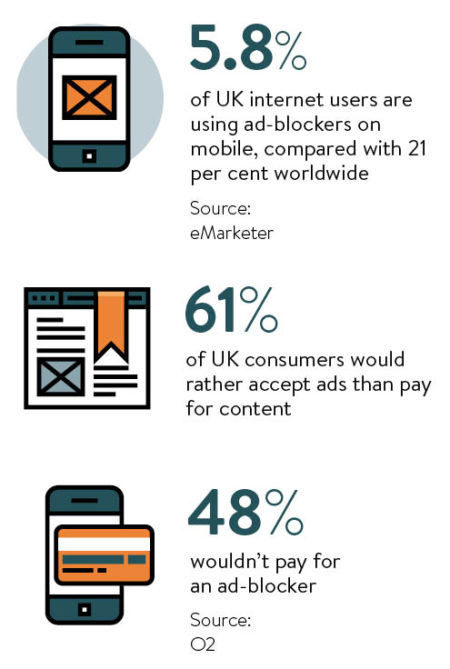

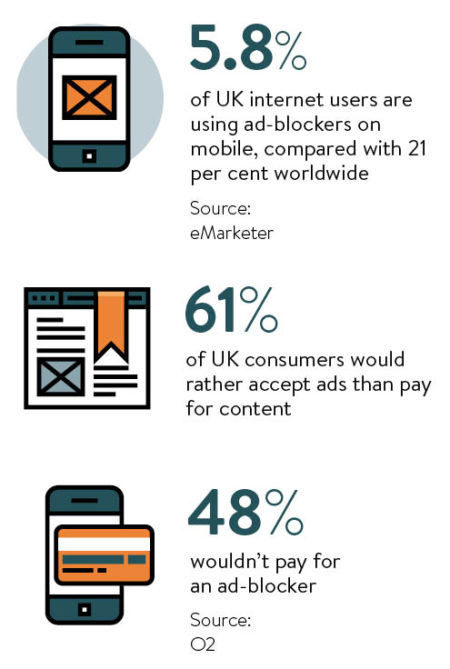

Libby Robinson, Europe, Middle East and Africa managing director of ad agency M&C Saatchi Mobile, says: “China, India and Indonesia are leading the charge with the highest number of ad-blocking browsers used globally.” She cites eMarketer data that shows 5.8 per cent of UK internet users are using ad-blockers on mobile compared with 21 per cent worldwide.

Stuart Bowden, global strategy officer at media-buying agency MEC, says Google and Facebook, the two biggest platforms for mobile advertising, have been able to fend off the threat of ad-blockers because their mobile apps are “walled gardens” where blocking technology largely does not work.

“That means the effect of ad-blocking is focused on their weaker, more traditional, open mobile web competitors,” says Mr Bowden. “Many of these sites respond by trying to increase the amount of ad units on their mobile pages, which just exacerbates the problem and drives more ad-blocking.” The ad overload can be “gruesome”, he warns.

Costly content

Nigel Clarkson, UK managing director of Yahoo, believes the adoption of ad-blockers may be stabilising as smart publishers learn from consumers’ behaviour.

“We are seeing as many as 15 per cent of people disabling their ad-blocker for various reasons, including their favourite websites asking them to, switching devices and not re-installing it, content being blocked as well as the ads, and the ad-blockers not working properly,” he says.

Making consumers understand there is a value exchange – that advertising helps to fund the cost of content and if they refuse to accept advertising then they will have to pay – is crucial.

O2 has found most consumers still want ad-funded services despite their misgivings about mobile advertising. “According to a survey we conducted earlier this year, 61 per cent of consumers would rather accept ads than pay for content and 48 per cent wouldn’t pay for an ad blocker,” says Mr Franks.

If the ad experience is good, clean and non-interruptive, and the targeting is relevant, consumers are happy to accept the ads

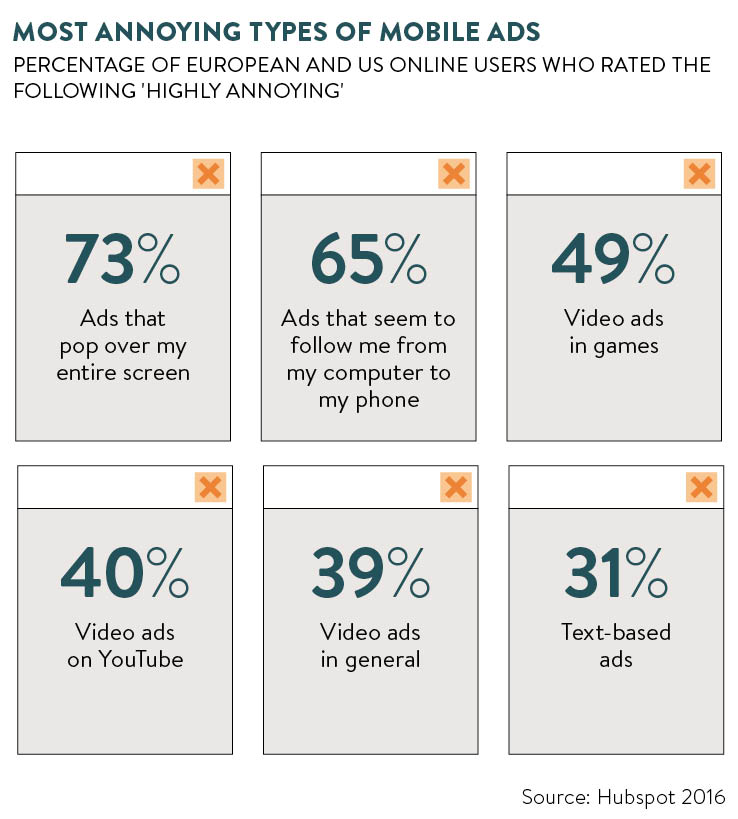

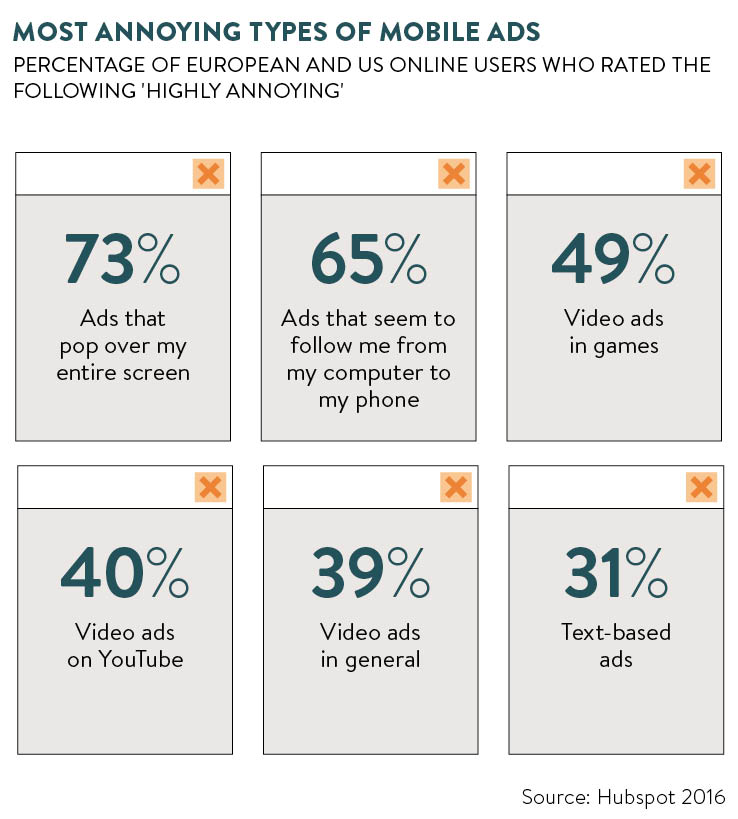

He goes on to cite research by the Internet Advertising Bureau, the trade body for the online ad industry, which identified a number of reasons why users are blocking ads. Firstly, they feel such ads are interruptive or annoying. Secondly, they worry that ads slow down web-browsing. Thirdly, they feel the ads may be irrelevant. Fourthly, they have privacy concerns.

Customer centricity

Ms Robinson of M&C Saatchi Mobile believes annoying, interruptive ads are the single biggest “frustration” for consumers and this has driven the adoption of ad-blocking. Despite the efforts of reputable, leading companies to clean up the mobile ecosystem, she warns: “Unfortunately, there have been an increasing number of rogue ad players looking to monetise by duping consumers into unintended engagement.”

She says it is not difficult to give people what they want. Being able to skip ads and being able to stop ads that slow page-loading are the top priorities for consumers, according to Ms Robinson. “This demonstrates that there is still a lot of work to do on the basics,” she says. “Advertisers need to understand that you can’t just repurpose print or digital ads for mobile; you need to design for the screen and most importantly for the consumer.”

Mr Clarkson of Yahoo agrees. “I think that ad delivery and experience are more important than targeting when it comes to creating better consumer feeling towards ads,” he says. “If the ad experience is good, clean and non-interruptive, and the targeting is relevant, consumers are happy to accept the ads.”

Mr Franks says creating relevant, personalised advertising can work, but it must be done with care. “Mobile is a much more personal device and therefore the risk of getting advertising wrong can be higher,” he says, noting the European Union is bringing in tougher rules, called the General Data Protection Regulation. “But equally the opportunity is far greater for richer, more immersive experience, if advertisers have the right permissions and can leverage the sensors on the device to offer an amazing experience.”

He explains how Weve, O2’s mobile advertising platform, has created mobile ad campaigns for leading automotive brands that utilise the gyroscope in the phone to enable consumers to have a 360-degree look around the inside of a new model of car to promote its launch – an innovative and highly engaging form of mobile marketing.

Mr Clarkson is also optimistic and rejects the suggestion that the smartphone screen is too intimate and personal to work for most advertising. “Quite the opposite,” he declares. “A mobile screen held up to eye level has a similar arc of vision to being sat ten feet away from your wall-mounted television.

“The personal nature of the screen means deeper engagement and the ability to touch, scroll, and control ads is a far better tool for creatives and clients to play with. The bigger challenge is getting creative teams to think about mobile experiences differently to other screens, for example making vertical video content which sits better in mobile.” A ten-second clip might work better on mobile than a classic, thirty-second TV spot, says Mr Clarkson.

Mr Bowden says the media and marketing industry needs to challenge itself to be far more radical in the way it uses mobile. While Mr Clarkson believes the rise of “native” advertising, particularly video, which blends in with content and is not interruptive, is the way forward.

New technological opportunities, which are likely to emerge in the near-future, excite Mr Franks. “Augmented reality has the potential to deliver a truly engaging experience,” he says, recalling the recent craze for mobile game Pokémon GO. “Another interesting development is ‘cross-screen’ where advertising can be delivered on different devices that consumers are using.”

The so-called internet of things, which will mean we can control household appliances and cars from our phones, opens up other marketing opportunities.

Whatever the future for mobile, we can be sure we will be spending a lot of time with portable devices. And where people go, advertisers follow.

Costly content

Customer centricity