By any measure the UK has one of the most advanced and developed mobile phone markets on the planet. Walk up any high street and there’s no doubt that we have an insatiable desire to interact and transact on our handsets.

The UK is ranked in the top ten globally when it comes to harnessing information technology, according to a recent ranking by the World Economic Forum. It helps that the telecoms market is one of the most competitive and regulated in the world.

“The UK’s smartphone appetite for faster mobile speeds continues to grow,” says Derek McManus, chief operating officer at O2. “Four in every five adults own a smartphone and 4G data usage has almost doubled in the last year. The consumer appetite and growth opportunity are clear.”

“The UK’s smartphone appetite for faster mobile speeds continues to grow,” says Derek McManus, chief operating officer at O2. “Four in every five adults own a smartphone and 4G data usage has almost doubled in the last year. The consumer appetite and growth opportunity are clear.”

Markets such as South Korea, Japan and the United States have long led the global race, but for some measures the UK ranks favourably. For example, access to phone banking is far more advanced here than across the Atlantic. The UK also has some of the world’s fastest mobile internet speeds, according to a report by content delivery company Akamai.

“We know that 92 per cent of British millennials now view their mobile as their primary device for accessing the internet,” says Chris Worle, digital strategy director at investment firm Hargreaves Lansdown. “The UK has one of the most sophisticated markets in the world.”

And when squared up to Continental Europeans, the UK is a 600-pound gorilla – it’s one of the largest in terms of subscribers, as well as total revenues, and has some of the most competitive pricing. It is also one of the most advanced in terms of roll-out and up-take of 4G. So the market should be in rude health, right?

Competition for consumers

Not quite. While brand names have evolved over three decades alongside handsets, the big players driving the market have largely stayed the same. Four operators dominate – BT’s mobile business EE, Vodafone, Hutchison’s Three and Telefonica’s O2 – all heavyweights on the international scene.

“Had the merger earlier this year between O2 and Three not been stopped by the EU, things could have been very different,” explains Ernest Doku, telecoms expert at uSwitch.com. “Austria reduced its operators from four to three and prices there soared by up to 30 per cent.”

The regulator wants BT to place more emphasis on improving the network, but this will be costly

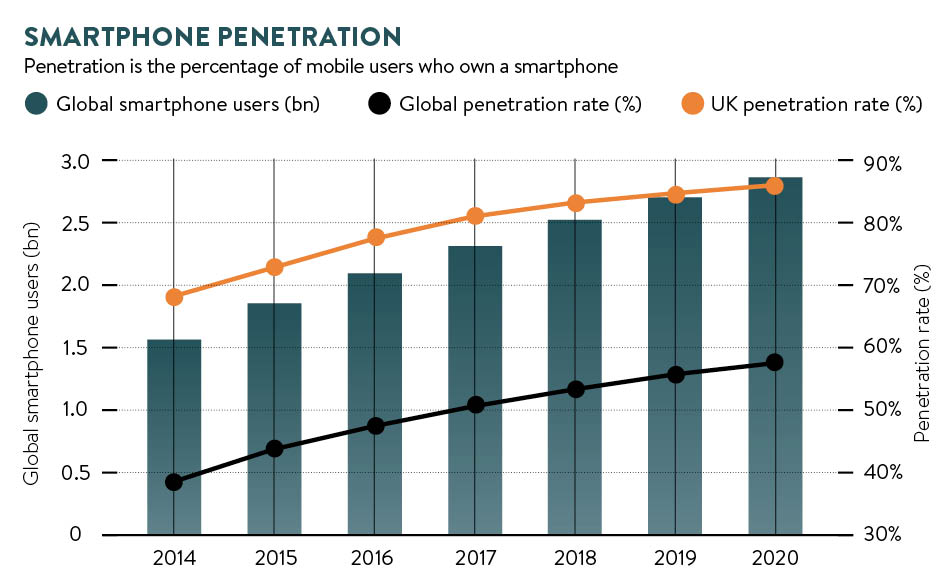

Competition is fantastic for consumers, but it’s not great for a sector that’s been consolidating globally because of price squeezes. The UK is also highly saturated, for instance mobile penetration in the US and Europe’s big five countries has reached 91 per cent, according to research by Kantar, and now ageing infrastructure dogs the sector.

“The return on investment for mobile operators is meagre to say the least. This needs to be addressed,” says Simon Beresford-Wylie, chief executive of Arqiva, providers of mobile infrastructure.

Telecoms companies have also complained about BT’s lack of investment in infrastructure. Many were disappointed when the regulator did not force it to sell its Openreach business outright. This company owns the pipes and cables that connect nearly all businesses and homes in the UK.

“The regulator wants BT to place more emphasis on improving the network, but this will be costly,” says Helal Miah, investment research analyst at the Share Centre.

If we’re not a 5G leader, there will be negative consequences for the economy and our global competitiveness

The UK was at the forefront of deployments in 2G and 3G. When 4G came along, the country lagged behind South Korea, Japan and the US. Many European markets already have 100 per cent coverage; the UK does not.

South Korea will also unveil the next generation 5G in 2018 to coincide with the Winter Olympics. In the UK, it is unlikely to be launched until at least 2020.

“5G will be important since it has the potential to support a whole new range of applications and industries. If the UK is serious about having a vibrant digital economy, being a 5G leader is a must,” says Mr Beresford-Wylie.

“This will be a basic competitive requirement for advanced economies. If we’re not a 5G leader, there will be negative consequences for the economy and our global competitiveness.”

Present picture

Yet who is going to utilise these services? At present the consuming public is suffering from handset fatigue, which shows few signs of abating. This not just a national issue but something with global impact, which is keenly felt in the UK where Apple and Samsung dominate.

Globally mobile services are now becoming more like other utility services and therefore as time progresses the consumer is increasingly differentiating contracts in terms of price. “Let’s hope that we don’t end up with a mobile market that resembles the supermarket sector,” says Mr Miah.

Some providers have now made strides towards new payment structures, separating airtime from handset costs, for instance. “But we’re some way from a truly value-driven market in terms of what customers are getting for their money in a European context,” says Mr Doku.

One of the biggest developments in the UK going forward will be the increasing uptake of multi-play services, broadband internet, television and telephone with mobile thrown in, also called quad-play.

Consumers are used to separate suppliers, but this situation is changing. “Convergence is key and what that means for pricing discounts,” says Guy Peddy, head of European telecoms research at Macquarie Group.

The question is whether fast-growing and profitable mobile services should subsidise fixed lines or ageing infrastructure. “The main challenges facing operators will also be maintaining voice prices anywhere close to current levels in this multi-play environment,” explains Dr Windsor Holden, head of forecasting at Juniper Research.

Making the UK’s mobile sector work and pay in the years to come could be a tricky business.