Artisan bread, herbal remedies, chemical-free cleaning products and carefully sourced food supplements – our shopping baskets overflow with “healthy” choices these days.

Indeed, the market for natural and organic products has never been brighter. According to Jim Manson, editor of Natural Products News, business optimism is high among independent health store owners as footfall and spend continues to rise.

“Sixty three per cent of 100 retailers polled in our Health Check survey reported increased store footfall – up 10 per cent on the 2015 survey – while 72 per cent said average customer spend had risen over the previous 12 months,” he says.

The taste for natural products may feel very 21st-century, but pre-industrialisation all farmed produce was inherently organic. And the idea of natural living dates back to Victorian times with the invention of wholesome-sounding foods such as granola and digestive biscuits.

But it was in the 1940s that academics first suggested farming needed to rediscover its holistic, ecological balance – an idea which became widespread in the 1970s when it chimed with a growing global environmental movement.

Since then we consumers have become comfortable with choosing items that are natural or organic. Perhaps the only worrying issue is that we can’t always distinguish between the two.

Renee Elliott, founder of Planet Organic, which sells organic and healthy produce and groceries online and in seven London stores, agrees. “It is understandable for consumers to confuse the two terms,” she says.

The rules of organic

So what are the rules? In essence, natural and organic products are produced without any synthetic material or chemicals being added.

More specifically, organic products in the European Union must comply with a set of standards, which include avoiding pesticides, and promote animal welfare. In the UK, the Soil Association is responsible for certifying more than 70 per cent of the growing organic market.

Natural products are defined by the Food Standards Agency, which states that these products should comprise of ingredients produced by nature and not by man. It does not specify that ingredients must be produced to high organic standards such as a transparent supply chain or avoiding the use of pesticides during farming. But it would be misleading to use the term “natural” to describe foods or ingredients that include chemicals to change their composition, including additives and flavourings.

More and more people are becoming aware of the benefits of natural ingredients both in food and in skincare

Ms Elliott explains: “The more complex or ‘manufactured’ a product becomes, the link to the soil and to agriculture becomes less obvious. Because of this we tend to think of an organic shampoo as being a ‘natural’ shampoo and so it will often be marketed this way for two reasons.

“Firstly, it is not obvious what the agricultural ingredients in the shampoo are that were organically grown, so that our intuitive understanding of ‘organic’ does not apply, and secondly because the organic products and brands sell themselves as being free from artificial ingredients, not containing this compound or a particular preservative or detergent, and so they are marketed as being a ‘natural’ product.”

[embed_related]

Increasing public enthusiasm

The wider choice of products reflects a booming public demand, says author Janey Lee Grace, who runs the recommendations site www.imperfectlynatural.com. She says: “More and more people are becoming aware of the benefits of natural ingredients both in food and in skincare.

“For years parents, for example, have carefully checked ingredients on foods to avoid E numbers or added sugar, but now we have a generation of people who are concerned about the potentially toxic ingredients in their skincare and personal care products too. In addition, there is more awareness of allergies and ‘free-from’ products, and also of course a concern around damaging the planet.”

Moreover, Ms Grace points out, natural skincare is affordable and available too. “Consumers recognise they can have the best products that just happen not to contain unnecessary toxins,” she says.

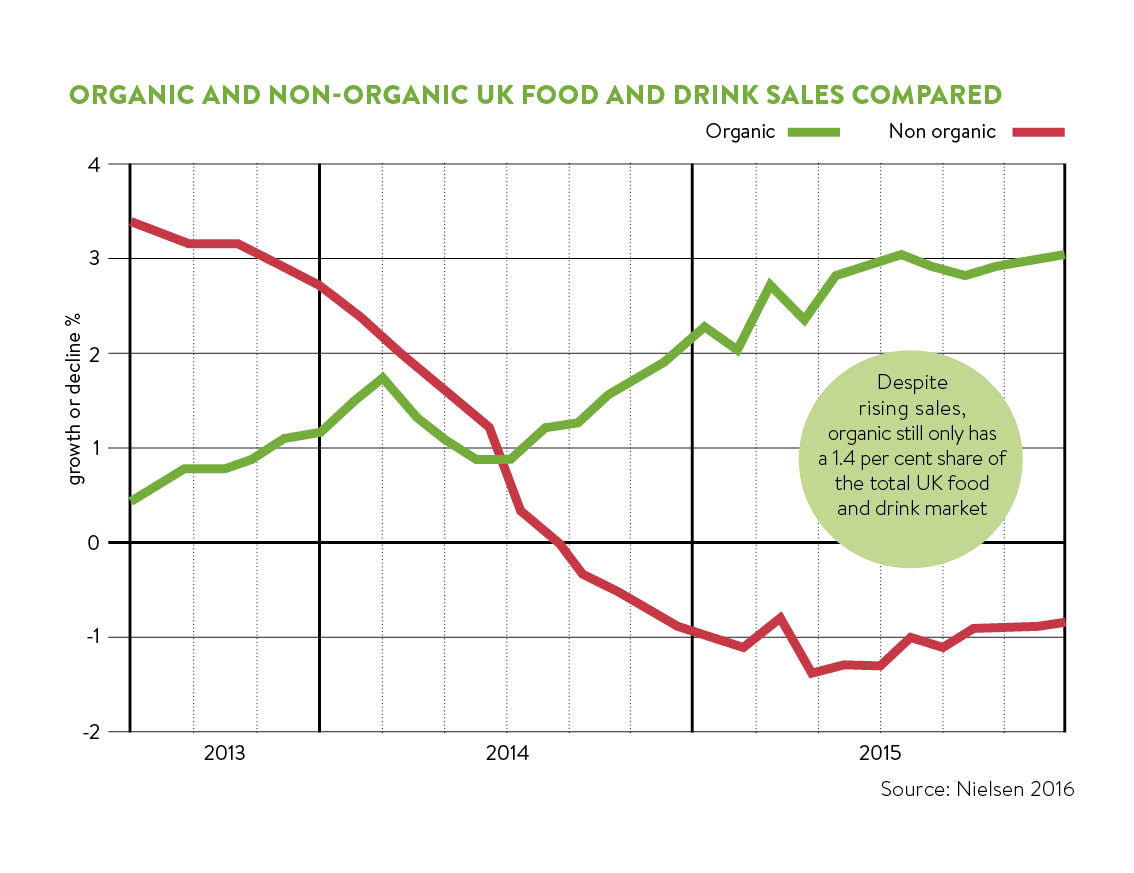

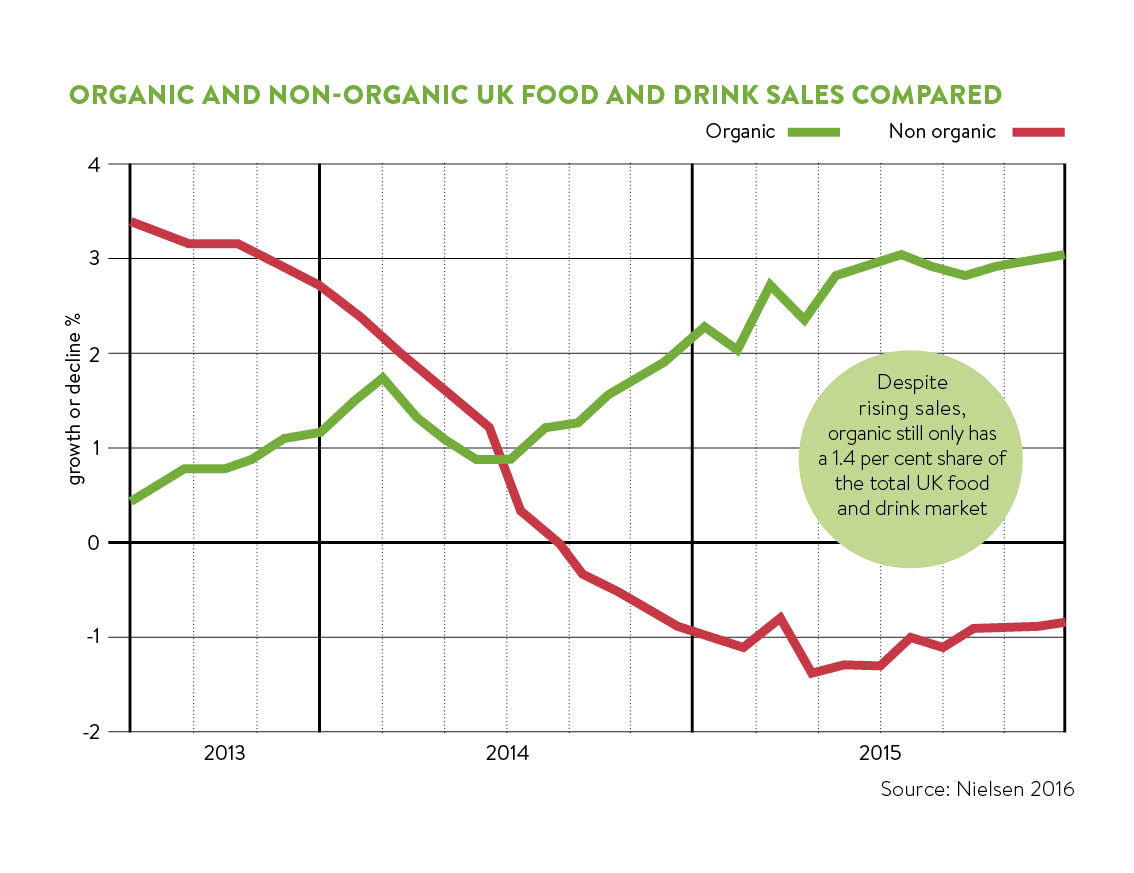

Ms Elliot agrees that public enthusiasm is translating into sales. “The majority of the UK population have now purchased organic products,” she says, “and there are some key categories, such as baby food, where organic has become the norm.” The Soil Association has reported sales of organic products rose last year by 4.9 per cent to £1.95 billion in the UK and sales of non-organic food dropped by 0.9 per cent.

Growth is set to continue with the worldwide organic market now worth £50 billion and all markets showing strong growth, says Catherine Fookes, campaign manager for the Organic Trade Board, who is not concerned that people in the UK still buy less organic and natural foods than their European peers.

“The UK per capita spend on organic is one third that of Germany – the largest organic market in Europe – and so there is much head room in the market,” she says. “The organic consumer is now younger than ever before, and it’s the 25 to 35 year olds who are largely responsible for driving this growth due to their interest in fitness and clean living. As these trends are only becoming more popular among a younger demographic, the growth of the organic market shows no signs of abating.”

Ms Elliott attributes the current lower sales to food culture and food retailing. “We have few choices of where to buy our food from, limited to a small handful of nearly identical retailers. As such we can only buy the amount of organic that we are offered and sadly for most of the UK that is not much. Many European countries have specific organic retailers,” she says.

“A decade ago 80 per cent of organic sales went through supermarkets; that proportion has now fallen to 70 per cent, according to the Soil Association, as organic products have benefited from the broader retail trend towards sourcing produce from smaller local retailers and online shopping.

“Organic food is standard in schools and hospitals in Germany, and that government investment is seen as an investment in its nation’s health. I very much hope the UK government will also realise the NHS savings if it invested more in organic agriculture, organic food in schools and hospitals, and helped those of us who are working to promote organic to spread the message further and faster.”