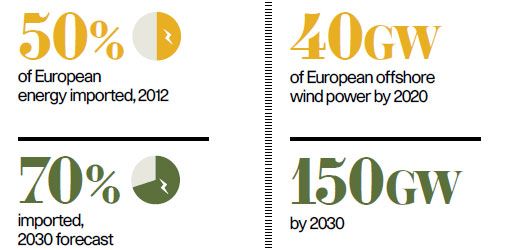

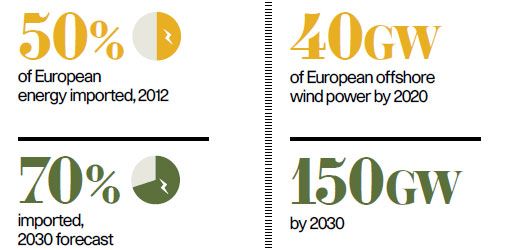

Europe currently imports 50 per cent of its energy and that figure is forecast to rise to 70 per cent by 2030 as domestic sources, such as North Sea oil and gas run out, and countries like France and Germany start to phase out their nuclear-power capacity.

Given the volatility of fossil fuel prices and political regimes of some of the countries that supply Europe, security of energy supplies is an issue that increasingly concerns policy makers.

Offshore wind is seen as part of a portfolio of energy-generating options that would make Europe less reliant on imported energy and less vulnerable to pricing fluctuations.

Wind energy is also renewable so it has the added benefit of contributing to the European Union’s 2020 energy targets: reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent; improving energy efficiency by 20 per cent; and generating 20 per cent of energy consumption from renewable energy. So how large an impact can offshore wind have on Europe’s energy-generation mix?

According to the European Environment Agency, installed capacity for offshore wind will be 44.2 gigawatts (GW) by 2020. The European Wind Energy Association comes to a similar conclusion, estimating that by 2020, 40GW of offshore wind power will produce 148 terawatt hours (TWh) annually, equivalent to more than 4 per cent of the EU’s total electricity demand and avoiding 87 million tonnes of CO2 emissions.

Wind gives us energy security because it reduces the need to rely on expensive imports of fossil fuels

Between 2020 and 2030, a further 110GW of offshore wind capacity will be added in European waters. This would mean 150GW of wind power would produce 562TWh annually, covering 14 per cent of the EU’s 2030 electricity demand and avoiding 315 million tonnes of CO2 emissions.

This is at the optimistic end of forecasts – 14 per cent is a substantial contribution to the renewable-generation mix – and much must happen to ensure this scenario becomes reality.

“At a time when Europe is at a major crossroads for its energy future, offshore wind provides a powerful domestic answer to Europe’s energy supply and climate dilemma,” says Gunther Oettinger, European commissioner for energy. “However, this development will not happen without ambitious national programmes and support from the European Union, underpinning the market promise.”

One critical programme is the development of an offshore grid. There are 11 in existence with a further 21 others planned for the North and Baltic Seas. Linking them would create a pan-European electricity “super highway” that would enhance security of supply, both by allowing countries to buy, sell and deliver wind power when they had a surplus or shortage, and by reducing the need for energy imports from outside Europe.

Policy makers must also commit to investing in the infrastructure and industry to turn the potential into reality. The pay-off for investment and regulatory support will be jobs as well as giving the EU “first-mover” advantage in the offshore wind global market.

With offshore wind projected to grow the most rapidly of all renewable technologies, with installed capacity multiplying 17 times between 2020 and 2030, its impact on reducing the eurozone’s reliance on imported energy and improving energy security will become an increasingly important one.

“There is a major opportunity for Europe to harness its huge offshore wind resource, to ensure that we can generate the maximum amount of clean energy from a domestic source which will never run out,” says RenewableUK’s director of offshore renewables Nick Medic. “Wind gives us energy security because it reduces the need to rely on expensive imports of fossil fuels. The construction of new infrastructure, such as interconnectors between European countries, will help to maximise the benefits of this power source.”

INDUSTRY BATTLES TO CUT ENERGY COSTS

PRICING There is no getting away from the fact that offshore wind is currently an expensive way to generate electricity.

Figures from Bloomberg New Energy Finance show that the sector is more expensive than all technologies, except marine energy and solar thermal generation.

Among the key areas that need to be tackled are the cost of finance, technological improvements and how the supply chain can contribute.

The cost of finance will not fall until the industry has been derisked, which means reliability must be established throughout the supply chain.

And while technological innovation is needed, if the pace of change is too fast, the supply chain will not be able to keep up and the risk will remain.

“There are two main things that need to be worked on,” says John Sturman, chairman of the Offshore Renewables Group at the Institute of Marine Engineering, Science & Technology. “One is getting the cost of turbines down and the second is to reduce the cost of foundations.”

Initiatives such as the Crown Estate’s Offshore Wind Cost Reduction Task Force and the Government’s Offshore Wind Component Technologies Development and Demonstration Scheme aim to cut the cost of offshore wind power to £100/MWh (per megawatt-hour) by 2020.