Have you ever considered how many people have handled a bag of salad or packet of pasta before it has made its way onto a supermarket shelf? Or how many shoppers have picked it up and then put it back?

There’s no evidence to suggest coronavirus can be passed on through touching packaging and the official stance from the World Health Organization is that packaging is an unlikely transmission route, despite the fact that the virus can survive on plastic for up to 72 hours. Nevertheless, attitudes and behaviours have understandably shifted over the past few months.

A survey conducted by FMCG Gurus, published in April, found 26 per cent of respondents across 18 countries, including the UK, United States and China, said they would now like more information about how products on shop shelves have been handled, while 42 per cent said they are paying more attention to the quality of packaging.

The pandemic has made people more anxious about germs and hygiene etiquette. Supermarkets and shops have taken measures to lower the risk of COVID-19 spreading, including installing hand-sanitising stations. But even once a vaccine has been found and administered, there will be shoppers who are likely to remain wary about germs being passed on by touching and handling products.

One solution to the problem, and the issue of contamination in the supply chain in general, could be self-cleaning plastic.

Researchers at McMaster University in Canada made headlines last December when they announced they had developed an anti-bacterial, non-stick plastic surface through a combination of clever chemistry and engineering. The transparent wrap is effective in repelling all forms of bacteria, including superbugs MRSA and Clostridium difficile, as well as viruses with a similar structure to COVID-19. It could potentially be used to shrink-wrap all kinds of things, from door handles to food.

The price challenge of self-cleaning plastic

The science for self-cleaning plastic is established, but it could be some time before bacteria-repellent materials are used to wrap products found in supermarkets.

Kinross-based Exporta, a packaging solution firm, which sells an anti-bacterial, self-adhesive film that can be applied to hand railings, tables and chairs, supplies clients in the agriculture, pharmaceutical and healthcare industries.

Don Marshall, Exporta’s head of ecommerce and fulfilment, says: “I can see the film’s application on the bulk side of distribution on plastic pallets, containers and boxes. Surfaces in the supply chain for moving goods are already hygienic and can be easily sanitised, but this would offer an extra level of protection.

“The problem with any technology, though, is that it remains expensive. Our film, which isn’t exactly self-cleaning, costs more than £1,000 a roll. So, if self-cleaning plastic was used for product packaging, it would add a hefty amount of cost to each product and increase the price of goods, which are already price sensitive.”

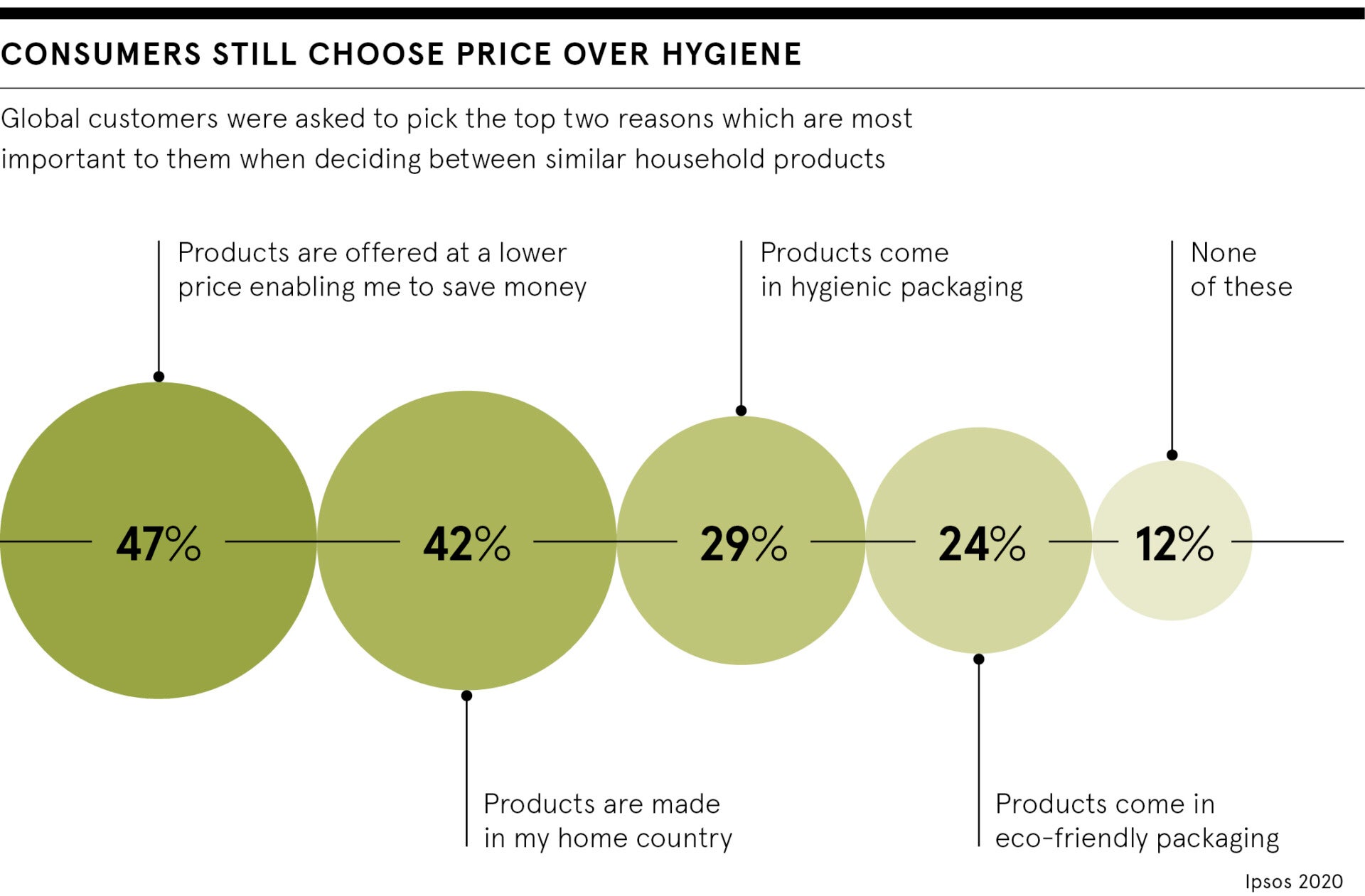

Industry analysis, published by Ipsos in August, has indicated that consumers might be more willing to buy a product if the packaging has proven hygiene qualities. However, a balance will need to be struck between hygiene, sustainability and value.

A survey of 16,000 people across 16 countries, conducted by the market research firm, asked what the two most important factors in deciding between two products of similar quality and features are. Nearly five in ten said lower price, 29 per cent voted for hygienic packaging and 24 per cent would prefer a product that came in eco-friendly packaging.

Putting safety before profit

Even if bacterial-repellent materials were to become mainstream, reluctance from manufacturers and retailers could stand in self-cleaning plastic’s way.

Stafford-based supplier of additives for plastics and textiles, Addmaster’s most innovative development is a coating for packs of fresh chicken that comes in both a liquid and powder form and helps to prevent the spread of bacteria, such as campylobacter, a common cause of food poisoning.

According to findings from the Food Standards Agency, campylobacter is present on 5 to 7 per cent of all chicken packaging. Cook-in-the-bag chickens, which are sold as a product where consumers don’t have to touch raw meat, can also be contaminated on the outside.

“The technology only adds 0.25p to the average price of a whole chicken, but numerous retailers and chicken suppliers have told us that this is too much, because of the amount of the meat eaten in the UK,” says Paul Morris, Addmaster’s managing director. “It’s tremendously frustrating to have the solution available, yet be hitting a brick wall with retailers that are putting profit before safety.”

Morris is hopeful the pandemic will mean retailers become more receptive to the technology. More shoppers now want anti-bacterial protection and raising hygiene standards will help companies increase their profits.

“Companies are beginning to realise that if they don’t up their hygiene game, then consumers will move to those that do,” he adds.

Similar hurdles face self-cleaning plastic. However, if the price is right, then it should become commercially viable.

“The development and rollout of self-cleaning plastic is definitely possible,” says Marshall at Exporta. “Like all new technologies, we need to see an increase in supply and demand, as well as adoption, for prices to drop to a point where it could be viable to have bacteria-repellent materials used for a packet of cornflakes.”

Have you ever considered how many people have handled a bag of salad or packet of pasta before it has made its way onto a supermarket shelf? Or how many shoppers have picked it up and then put it back?

There’s no evidence to suggest coronavirus can be passed on through touching packaging and the official stance from the World Health Organization is that packaging is an unlikely transmission route, despite the fact that the virus can survive on plastic for up to 72 hours. Nevertheless, attitudes and behaviours have understandably shifted over the past few months.