Over the last few years, a hurricane has swept through the established photographic landscape, commercial and social, and is now creating opportunities to build afresh with new materials, ideas and concepts.

A new topography has been drawn and a new creative environment built with the tools of photography by the digital natives and open-minded practitioners who are mastering those tools.

It is the immediacy and the scale of globalisation and the democratisation of today’s technological innovations that make this such an exciting time to be engaged with photography. The scale of capture is vast and sees a greater number of images taken, uploaded, shared and tagged daily than ever before.

Projects such as What’s Next? curated at the Amsterdam gallery, FOAM, provoke dialogue and investigation of future photography. It is encapsulated in Erik Kessels’ 24 hours in Photos installation, an overwhelming presentation of every image uploaded to Flickr in a 24-hour period.

The scale of capture is vast and sees a greater number of images taken, uploaded, shared and tagged daily than ever before

With these changes, photographers are now able to become commissioner, producer and publisher of their own work. Through social media channels, such as Twitter, Facebook and Flickr, they can communicate ideas and share work directly with and gain a better understanding of their audience. Audiences are, in turn, also able to build and form relationships with photographers and, via crowd funding, become patrons of their work in ways not possible before.

These mutual relationships have also seen other positive benefits; field work that previously was perhaps not deemed commercially viable or to have a mass appeal, can now be made, brought into the public domain and given the opportunity to shine. Crowd-funding platforms, such as Kickstarter, provide an opportunity to back creative projects and in return receive an award for support.

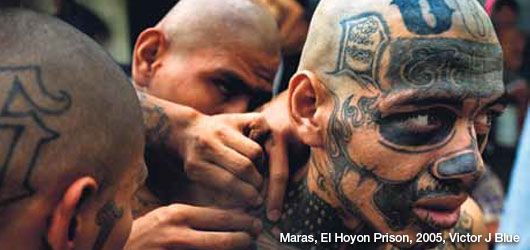

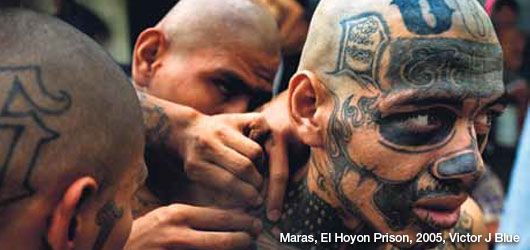

Pete Brook, editor of Prison Photograph, and writer for Raw File, Wired’s photography blog, put forward a persuasive proposition in Prison Photography On the Road. “I wanted to involve the community at every level I could,” he says. “Dozens of photographers, including Vic Blue, donated prints to raise money. Crowd funding is community funding; it involves the community. Together we tackled the hard issue of prisons in an engaging, novel way… and now it’s out there for the world.”

These new landscapes bring other opportunities to the work with new licences and tools offered through initiatives, such as Creative Commons, which encourage and maximise sharing and innovation.

Working and exploring this digital terrain provides opportunities for students. Coventry University, for instance, runs two open undergraduate photography classes, picbod (picturing the body) and phonar (photography and narrative), which have engaged more than 60,000 people across the globe and nearly a million through iTunesU.

Marta Kochanek, a phonar graduate mentored in an “open” and “connected” environment, realised her dreams through working for her idol Annie Leibovitz. Following that, she produced a series of photographs of Tim Andrews, whose Parkinson’s disease inspired him to model for documenting the illness and reaching others. For Kochanek, sharing means “Provoke others’ imagination… Share it to let the audience be here and now, as if they took part in the creation.”

Over the last few years, a hurricane has swept through the established photographic landscape, commercial and social, and is now creating opportunities to build afresh with new materials, ideas and concepts.