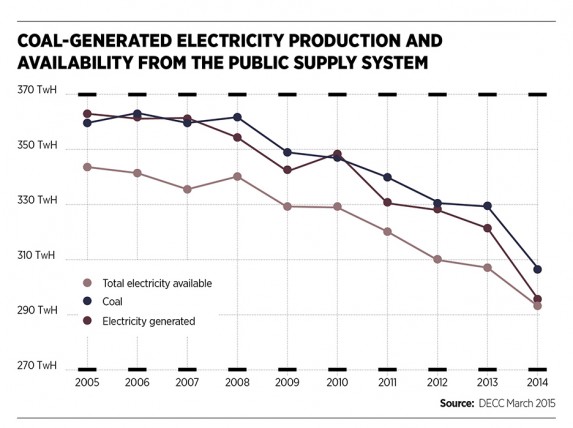

The days of coal being king in the UK energy market are long gone. Current capacity is around 20 gigawatts (GW), down from some 28GW in 2012, according to the Department of Energy and Climate Change. And that is expected to fall further over the next five years, with operators feeling the heat to meet lower-emissions standards.

The European Commission has set three key objectives for 2020 piling on that pressure:

- A 20 per cent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels;

- Raising the share of EU energy from renewables to 20 per cent;

- A 20 per cent improvement in the EU’s energy efficiency.

By 2050, the EU also hopes to fully decarbonise the power generation industry. Against this context, EU legislation is harsh. Air quality regulations, such as the Large Combustion Plants Directive and the Industrial Emissions Directive, which limit sulphur dioxide (SOx), nitrogen dioxide (NOx) and dust, require plants that are not fully compliant by the end of 2015 to either close or run at a reduced load factor during their transition to compliance by 2020.

By 2050, the EU also hopes to fully decarbonise the power generation industry. Against this context, EU legislation is harsh. Air quality regulations, such as the Large Combustion Plants Directive and the Industrial Emissions Directive, which limit sulphur dioxide (SOx), nitrogen dioxide (NOx) and dust, require plants that are not fully compliant by the end of 2015 to either close or run at a reduced load factor during their transition to compliance by 2020.

As a member state, the UK is also on this path and that is unlikely to change regardless of the outcome of the pending vote on EU membership. The announcement this month by G7 leaders to phase out fossil fuels by the end of the century adds to the pressure.

Coal-fired generators are responding in a variety of ways, either through retrofitting emissions-reduction systems, conversions to other fuels such as biomass, reducing running hours or closing down completely, explains John Fogarty, chief engineer of Doosan Babcock. Indeed, last month British utility SSE said its last remaining unit at the 48-year-old Ferrybridge Power Station in Yorkshire will close by March 31, 2016, citing rising costs due to its age and environmental legislation. The plant is forecast to lose £100 million over the next five years.

The announcement this month by G7 leaders to phase out fossil fuels by the end of the century adds to the pressure

This is the latest in a series of coal plant closure announcements, including Scotland’s last remaining coal plant, the 2.4GW Longannet station, resulting from pressure to meet EU obligations.

Companies such as Doosan Babcock are working with those trying to stay open. “Power companies are ensuring coal generation is as clean as economically possible, driving down emissions though building state-of-the-art, high-efficient supercritical units across the world. These are fitted with advanced air quality control systems which have dramatically reduced the emissions per kilowatt-hour of these plants,” says Mr Fogarty.

The range of solutions being deployed across the industry includes:

- Primary emissions control through advanced low-NOx combustion systems;

- Secondary NOx controls through either selective catalytic reduction (SCR) or selective non-catalytic reduction (SNCR), which Doosan Babcock is currently installing at Drax Power Station in North Yorkshire. Typically, in SNCR systems, a reagent, such as ammonia or urea, is injected into the flue gas in the furnace and reacts with the NOx to form nitrogen and water, helping to reduce emissions of NOx by anything from around 30 to 50 per cent, says Mr Fogarty. SCR involves combining ammonia/urea with flue gas and passing it over a catalyst. This can achieve 85 to 95 per cent NOx reduction depending on the inlet conditions. Doosan Babcock recently designed and installed an SCR system for the four boiler units at the Ratcliffe Power Station in Nottinghamshire;

- Combustion and boiler technologies used to convert coal-fired plant so they can utilise biomass as a fuel source instead.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is also high on the agenda, with only new coal plants featuring the technology allowed from now on in the UK. “The real barrier is that the economic drivers are not in place to make it viable,” says Mr Fogarty.

Christian Schaible, policy manager on industrial production at the European Environmental Bureau, agrees. “Like every chemical process, it demands energy and therefore reduces the overall efficiency of power generation from coal. And while CCS could, in theory, take care of the CO2, getting rid of the other waste and upstream pollution is an issue that has not yet been properly resolved,” Mr Schaible says.

Moreover, CCS will only work if the carbon stays in the ground forever. “That is a big promise to make, poses regulatory risks and raises the question of how to insure against the leakage of possible CCS storage sites. Ultimately, this is an economic question,” he concludes.