There are some rather alarming statistics around the UK’s current energy situation.

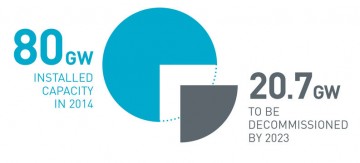

Last year, for example, the UK’s total installed capacity was approximately 80 gigawatts (GW), yet a quarter of that electricity capacity, 20.7GW, is due to be decommissioned by 2023.

That 20GW being retired leaves an estimated 20 million homes without power. Meanwhile, demand for new housing soars, with potentially up 1.2 million new homes due to be built by 2024.

More energy, not less, will be needed.

To add to this scenario, the government has cut subsidies for renewable energy generation onshore and has no cohesive strategy for how it plans to plug the energy gap.

In fact, decision-making on this crucial issue is falling increasingly to local communities and authorities rather than central government.

It is a scenario that Barton Willmore and its energy clients have been predicting and raising concerns about for some time.

Partner Gareth Wilson says: “The UK’s energy security is a national issue. Local decision-making and government policy for greater localism and cost-cutting is the wrong approach. Austerity measures have left local authorities without the capability or the capacity to determine the number of planning applications required or deal with the complexities of larger applications.”

The problem is that in spite of talk about “the lights going out”, the UK’s energy sector has reassuringly always maintained ‘”surplus capacity” that can be switched on to meet higher than normal demand.

But the nation has lulled itself into a false sense of security.

A number of power stations across the coal, oil and nuclear industries are now reaching the end of their lifespan, or being shut down for environmental or economic reasons, yet new capacity coming online is not keeping pace.

“We are closing or mothballing larger plant than we are opening,” says Mr Wilson. “The gap between capacity coming off and capacity coming on is growing, and it needs to be plugged if we are to maintain security of supply in the long term.”

The UK’s ageing energy grid infrastructure is another cause for concern. Unable to cope with new sources of energy generation that need to be connected to the main energy grid system, it has been deemed not fit for purpose.

“A lack of sub-station infrastructure that can cope with new energy production is a problem and the statutory authorities, the distribution network operators who are responsible for this infrastructure, are failing to deal with this issue proactively,” he says.

Then there are the high up-front costs of reserving capacity in the network that energy developers have to pay before planning permission is granted.

“A lot of our clients have experienced this,” says Mr Wilson. “These charges can be prohibitively expensive for smaller-scale energy developers, who tend not to have large cash resources available until planning permission is granted and also struggle to compete with the largest energy companies.”

This lack of infrastructure that prevents new energy generation to the grid is forcing developers to scale back the size of their energy projects and ultimately driving energy developers out of the market because it is no longer viable for them to operate. This has a negative knock-on effect on investor confidence, sending investors elsewhere, generally outside the UK, fast.

Yet in spite of a yawning energy gap, there appears to be a sense of complacency, possibly thanks to falling oil prices and the US shale boom as the UK is getting a good deal on its imported oil, gas and coal.

However, as Mr Wilson explains, our reliance on these imports is unsustainable.

“Wholesale prices are currently low, but this won’t always be the case. We need to wean ourselves of this before the supply dries up and prices go up, and also to maintain our commitment to emission-reduction targets,” he says.

To avert what looks to be a major crisis within the next decade, the consensus is that the UK needs a central government-led, fully funded and resourced National Energy Plan, with responsibility for delivering the critical infrastructure.

“This is something that we and our clients have been calling for – a national policy that will identify the type of energy mix needed for the UK over the next 25 years and suitable broad locations where this development will take place, away from sensitive areas. It will also determine how and when this energy mix will be delivered in the short, medium and long term,” says Mr Wilson.

Crucially, he adds, a National Energy Plan will detail the funding and incentives needed to deliver this infrastructure with cross-party consensus. This might include expediting new nuclear power stations, commitment to greater energy innovation around new and emerging energy technology, and provision of funding for research and development.

The clock is ticking, yet people are still unaware of the energy gap and what it will mean for the UK

It would certainly need to prioritise higher energy efficiency standards in new and existing homes and commercial properties.

There also needs to be greater collaboration with neighbouring countries to reduce reliance on imports from outside Europe.

One of the frustrations for energy developers and a potential stumbling block to devising a national plan is that the government’s main focus is on new housing, rather than energy. Yet the two are inextricably linked.

Housing completions for the financial year to April 2014 were 141,000, still below the pre-recession levels of more than 220,000 a year. If rates continued at 141,000 a year to 2023, this would equate to an additional 1,269,000 homes and the requirement of an additional 1.2GW of electricity capacity.

“The clock is ticking, yet people are still unaware of the energy gap and what it will mean for the UK,” says Mr Wilson. “Ensuring the UK’s future energy security has to become a priority and it will take government leadership to make it happen.”