For policymakers, the primary goal of electricity supply is to create a system capable of delivering clean, secure and affordable energy to consumers. Known as the “energy trilemma”, at face value these cornerstones of energy strategy appear to be at odds with each other.

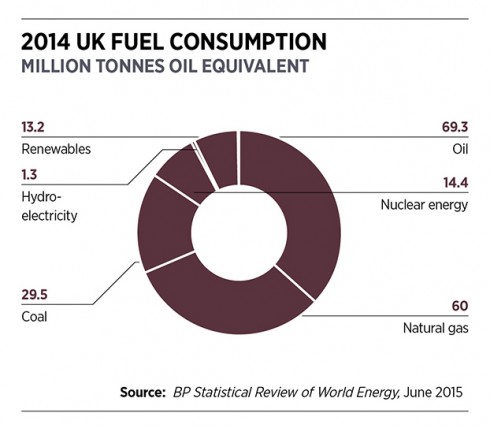

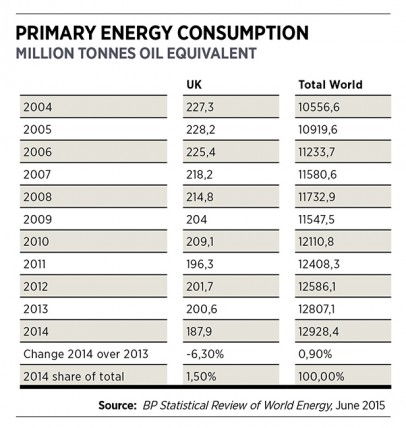

Decarbonisation is a key driver and under the auspices of European Union climate change initiatives, the UK has made a commitment to secure 15 per cent of all its energy supplies from renewable sources by 2020. Clearly this represents a significant step towards a clean, low-carbon energy system and delivery of its associated environmental benefits, particularly as this plan will see something above 30 per cent of all electricity coming from renewable sources.

According to recent figures from the Department of Energy and Climate Change, renewable electricity generation was 64.4 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2014, an increase of 20 per cent on the 53.7TWh seen in 2013. Furthermore, renewables’ share of electricity generation was a record 19.2 per cent in 2014, more than 4 per cent up on the 14.9 per cent of 2013. Meanwhile, the installed capacity of renewables was 24.2 gigawatts (GW) at the end of 2014, a 23 per cent increase on a year earlier.

Total renewables, as measured by the 2009 EU Renewables Directive, accounted for 5.2 per cent of energy consumption in 2013, up from 4.2 per cent in 2012. But, as impressive as this growth is, it suggests the UK will have to roughly triple its clean energy capability by the end of the decade and, within that, just about double the electricity contribution from renewables.

UK renewables investment in the five years since 2010 will have topped £50 billion by the end of 2015, according to a new report from PwC and the UK’s Renewable Energy Association. Investment in 2014 was at a record £10.7 billion, with offshore wind and solar attracting the largest share. Since 2010, an average of £7 billion has been invested annually, but as Ronan O’Regan, director of renewables and cleantech at PwC, notes: “Reaching the 2020 targets is estimated to require a further £50 billion of investment.”

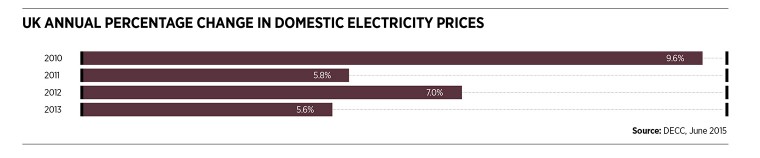

The UK’s 2014 National Infrastructure Plan puts the pipeline of investment in the energy sector as a whole at up to £100 billion in the electricity system alone by 2020. These additional costs are ultimately borne by the consumer.

While the success of policies supporting renewable energy is clear, the growth of renewables is also having other, perhaps unforeseen, impacts. On the right day and in the right location, wind and sun come at zero cost, whereas gas does not. As a consequence of renewable energy support mechanisms and the absence of operational costs, renewable energy generation can price out other forms of capacity in competitive electricity markets.

To ensure the lights don’t go out, additional measures have been required to secure sufficient generating capacity

Indeed, where renewable energy penetration is high, this effect can be so extreme that negative prices can result, as in Germany, with generators effectively paying to export power.

The paradox of the low-carbon energy policy and renewable energy growth is the potential threat to energy security. Coupled with EU Directives, such as the Large Combustion Plant Directive, conventional power plant closures are a continuing trend. Most of the UK’s existing nuclear stations are also due to close before 2023 with some 20 per cent of the country’s existing generating capacity set to shut down by the end of the decade.

But, with a question mark hanging over the investment case for new fossil-fuelled power stations, a capacity crunch is widely anticipated, marking a real threat to security of electricity supplies.

Indeed, UK capacity margins – the difference between supply and peak demand – are steadily falling. Energy regulator Ofgem notes that margins are expected to drop to their lowest level in the winter of 2015-16 as a result of a reduction in supplies from conventional generation, with a margin as narrow as 2 per cent anticipated.

To ensure the lights don’t go out, additional measures have been required to secure sufficient generating capacity. In March, National Grid called for bidders for reserve contracts to help balance the electricity system in the coming winter. This is a second round of tenders; the first late last year secured 700 megawatts (MW) of additional reserves.

In addition, earlier this month Amber Rudd, the new UK energy minister, announced that there would be a further capacity auction this autumn for delivery in 2019-20. This process commits generators to provide electricity when needed, but in return they receive a payment on top of the electricity price. Through the previous auction, government procured 49.26GW of capacity at a price of £19.40 per kilowatt (kW) or around £11 for the average household.

While the government resorts to costly market measures to secure sufficient energy supplies during the clean energy transition, many argue that the technologies needed to address these vexing issues are not from some far-flung future utopia – they are already here. Effective load shifting offers an opportunity to reduce peak demand through a number of mechanisms.

Sara Bell, chief executive of Tempus Energy, argues that the solution to the energy trilemma lies in demand flexibility. “If we are bringing in generation that is by its nature intermittent, we need to be sure that on the consumption side the bits that are flexible are used flexibly,” she says.

Examples of flexible demand include space heating or refrigeration where load can be shifted to low-cost, non-peak times without any impact on consumers. Tempus systems, for example, integrate with building-management controls for commercial premises to optimise power demand in respect of peak pricing and peak demand.

Ms Bell suggests the potential impact of a connected and responsive energy sector is significant. “I think in a totally connected situation, in winter you could get 20 per cent off the system [peak demand],” she estimates.

Sarah Blois-Brooke, senior consultant within the distributed energy project practice at Encraft, echoes this arguing that technical solutions are already available, but that market structures are proving a barrier to roll-out.

“We are trying to manage energy at community level and trying to maximise the use of generation within a community, but the way the market is set up is a very top-down approach. It’s difficult to leverage benefits for customers in the current market situation,” says Ms Blois-Brooke. “But the technology is there.”

Chris Wright, chief technology officer at Moixa Technology, adds: “Because we now live in the internet age, we can treat all of those [distributed storage] systems as if they were one [utility-scale] system by putting in a control platform.”

The energy trilemma is a complex challenge, but it seems that modern communications offer perhaps the best and lowest-cost approach to manage the clean-energy transition. It appears the barriers are not technical, but are more fundamentally associated with market structure. With the courage to take bold action, that’s something policymakers should be able to address.