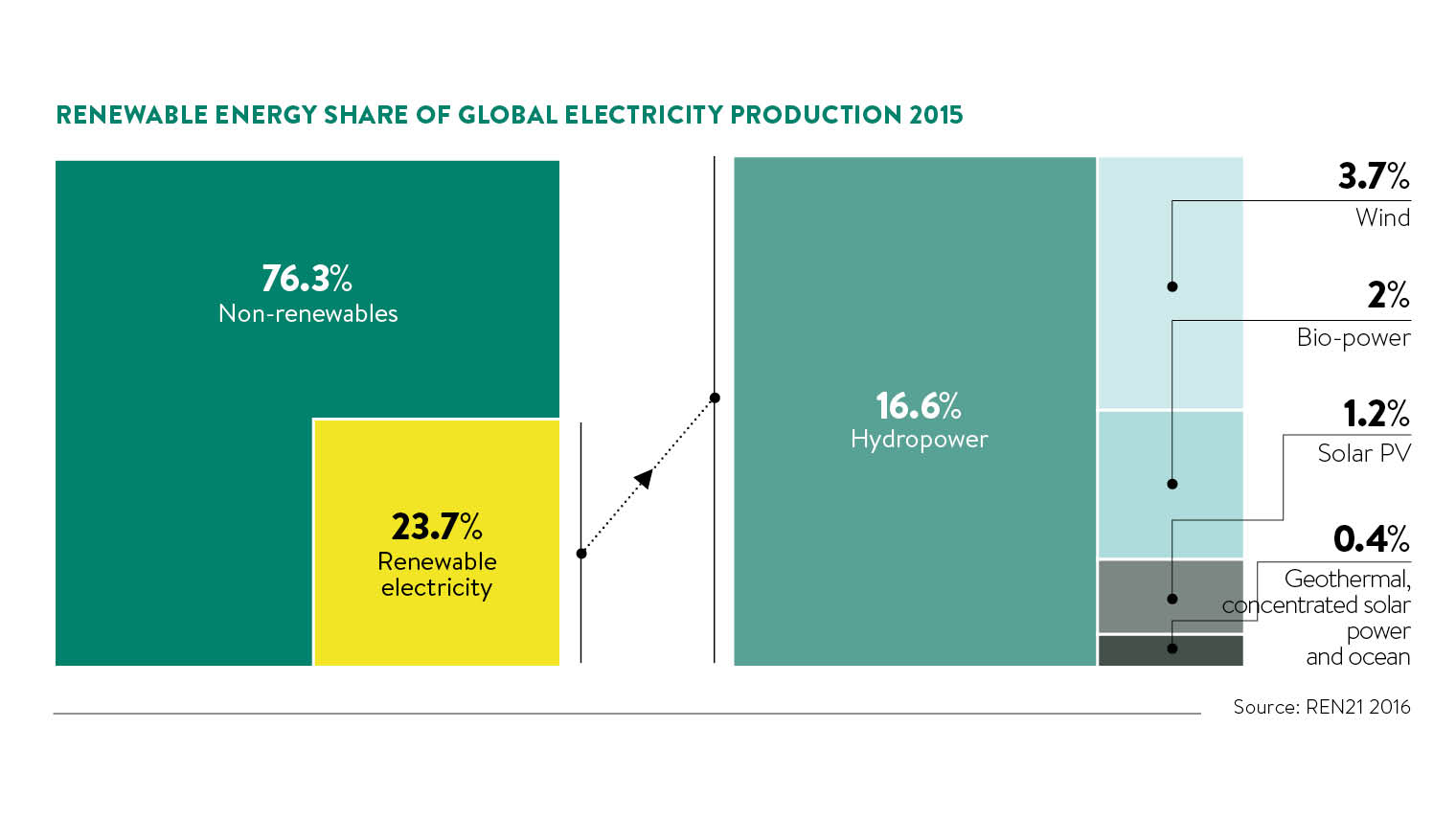

Business is good or so it seems. Growth in renewable energy worldwide continues to rocket, with the REN21 Global Status Report recording the largest annual increase in power capacity as an additional 147 gigawatts went live in 2015.

The megatrend is irresistible, says Assaad Razzouk, group chief executive and co-founder of Sindicatum Sustainable Resources. “Investments in renewables were double the spend on new coal and gas-fired power plants,” he says. “We will be drowning in junk oil, as electric vehicles and solar pursue their inexorable advance.”

The changing UK energy landscape

At first glance, UK numbers seem similarly conclusive, with government figures for renewable electricity generation up 28.9 per cent. However, not all fossil fuels had a bad 2015. Both oil production (13.4 per cent) and natural gas (7.8 per cent) were up, with only coal down (27 per cent).

At first glance, UK numbers seem similarly conclusive, with government figures for renewable electricity generation up 28.9 per cent. However, not all fossil fuels had a bad 2015. Both oil production (13.4 per cent) and natural gas (7.8 per cent) were up, with only coal down (27 per cent).

To muddy waters further, the picture is changing. Government pulling the funding plug last July on its failed Green Deal flagship left the struggling insulation sector in a policy void, facing thousands more job losses. The 65 per cent cut to the feed-in tariffs (FITs) last December also saw installation of small solar plummet this spring.

For all the excitement about the deal in Paris, it only scratches the surface of CO2 emissions required – there is much more to be done

Mired in delay and doubt, Hinkley Point C hangs in the balance on the Somerset coast, while support for Tidal Lagoon Swansea Bay ebbs away. In planning, onshore wind and solar farms encounter setbacks, but in a contrasting reversal of fortune, the first fracking operation in England since the shale ban lifted in 2012 won approval in North Yorkshire.

Meantime, citizen health and wellbeing remain a concern, with outdoor air pollution linked to 40,000 early-deaths in the UK a year, and more than 10 per cent of households in England are languishing in fuel poverty.

Paris climate conference

Given such mixed signals on progress towards a low-carbon economy, plus persistently low oil and gas prices, there can be no room for complacency in the clean energy sector, says Michael Liebreich, founder of Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “The scale of the changes required is really daunting,” he says. “For all the excitement about the deal in Paris, it only scratches the surface of CO2 emissions required – there is much more to be done.”

At the Paris climate conference (COP21) in December, 195 countries adopted the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal to limit global warming below 2C. Six months on from the talks, and with G7 nations also pledging to end fossil-fuel subsidies by 2025, the scales are tipping in the corporate world.

Mr Liebreich says: “For mainstream business, Paris was the start of a process by which the global clean energy transition switches from unlikely scenario to base case for long-term strategic planning.”

UN dignitaries including secretary general Ban Ki Moon (centre) and French president François Hollande (right) celebrate the adoption of the global warming pact at the COP21 Climate Conference in Paris last December

Business engagement made a big difference to COP21, argues Damian Ryan, head of international policy at The Climate Group. “The agreement undoubtedly marked a major turning point,” he says. “Prior to Paris, over 400 major businesses had made public commitments as part of the We Mean Business initiative. This groundswell of support had a real impact and helped close the deal. The business community now recognises governments are moving from negotiation to implementation.”

To date, some 65 companies have joined the RE100 initiative in committing to sourcing 100 per cent of their electricity through renewables. Among that number, Marks & Spencer is launching a unique community-based ethical investment initiative.

Getting creative around carbon reduction

In a first for community energy, the £1.2 -million M&S Energy Society share offer will raise capital to install, own and operate solar panels on the roofs of stores, with all profits distributed locally via a dedicated community benefit fund.

Such pioneering initiatives represent a test case for the UK market and a learning experience for all concerned, says M&S head of Property Plan A and facilities management Munish Datta. “Our community solar initiative has taught us that unusual, innovative collaborations pose challenges in terms of risk and bring potential co-benefits of protecting the environment, involving customers and commercial viability,” he says.

Changes to FITs mean the business model must adapt, he adds. “For corporate-community solar to succeed in the future, it needs to be financially self-sustaining and formulaic,” says Mr Datta. “In the next three years the price of solar is predicted to come down by 40 per cent and installations could become 60 per cent lighter. These developments and applying lessons learnt will make it easier for community solar to succeed.”

At Göss in Austria, innovation on the part of Heineken is also breaking new ground creating the first carbon-neutral large-scale brewery in the world. Utilising excess heat from a local sawmill is taking the beer maker beyond what it has done with wind turbines in the Netherlands, biomass in Vietnam and solar panels at Tadcaster.

Companies need to get creative around carbon reduction, says Heineken’s global sustainable development director Michael Dickstein. “We first look at our own operations, but to go one step further you have to think beyond the perimeters of your own business,” he says. “Mid to long term, the environmental and economic opportunities of renewable energy exceed the operational challenges, and can even become a competitive advantage.”

It is this mix of strategic vision and market ambition that marks out corporate leaders navigating the future grand transition. For the future of energy, it seems business is good.

The changing UK energy landscape

Paris climate conference