Eight million tonnes is a lot of plastic trash, from computer monitors and drinks bottles, flip-flops and fishing nets, to multi-coloured fragments and micro-particles. Landfill-site mountains would be bad enough, but this is worse – this is plastic dumped in oceans every year.

Research estimates 5.25 trillion plastic pieces currently at sea, mostly in five areas where currents converge, known as the gyres and likened to giant whirlpools or toilet bowls flushing.

Popular belief suggests a third of ocean waste is concentrated in one gyre twice the size of Texas, called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Plastic is responsible for loss of aquatic life, habitat damage and biodiversity risk

That phrase paints a somewhat misleading picture, argues documentary film-maker Angela Sun: “Public perception of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is that it is an island of trash, which it actually is not – it’s more a plastic smog or minestrone soup, woven into the marine ecosystem,” she points out.

Writer, director and presenter of award-winning documentary Plastic Paradise: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, Ms Sun is realistic about the guesswork involved in pollution statistics. She says: “We grossly underestimate the vastness of the oceans. There is no way to collect accurate data.”

What is not in doubt is that plastic is responsible for loss of aquatic life, habitat damage and biodiversity risk. Annual death tolls claimed include hundreds of thousands of marine mammals, plus up to a million seabirds.

Long floating barriers use the natural movement of the ocean currents to concentrate and collect the plastic passively

Global economic costs of ecosystem damage are also enormous, with conservative estimates from the United Nations Environment Programme running to $13 billion a year. So why don’t we just clean it up?

This was actually the question asked by Boyan Slat, founder and president of The Ocean Cleanup, in his 2012 TEDx Talk that went viral on YouTube. Not enjoying much success attracting project funding at the time, Slat was only 18. “I basically was a teenage university dropout with a crazy idea,” he says. “I tried getting sponsorships and asked foundations for support, but nobody was willing to take the risk.”

He turned to crowdfunding, with spectacular success. An initial $90,000 bankrolled feasibility, then a whopping $2.2-million campaign enabled pilot-testing.

“Without crowdfunding we wouldn’t have found the initial budget,” he observes. “Without social media we wouldn’t have been able to crowdsource the R&D team. Twenty years ago, this project probably wouldn’t have been able to exist.”

It is one thing to have an innovative idea, but another to manage everything that comes with a large-scale, complex project. Teambuilding becomes critical, he explains: “Engineering has always been of interest to me, personally. Building an organisation to facilitate technical problem-solving has been something I had to learn along the way. Key is to build a team with the right mix of dedication and skill.”

Balancing commitment and competence is not easy, acknowledges Alistair Godbold, Association for Project Management (APM) deputy chairman. “People who work on a project like this must believe in what they are doing with a passion,” he says. “These people with the right passion must have the right skill and experience to be able to deliver, and in today’s economy they are in high demand.”

According to APM board member Sarah Coleman, citizen involvement adds further project dimensions. She says: “Community represents an important set of stakeholders, who require careful engagement, management and communication. A key part of the project manager’s role is looking outside their organisation and governance team to the bigger picture, and environmental change is always going to be a big-picture topic.”

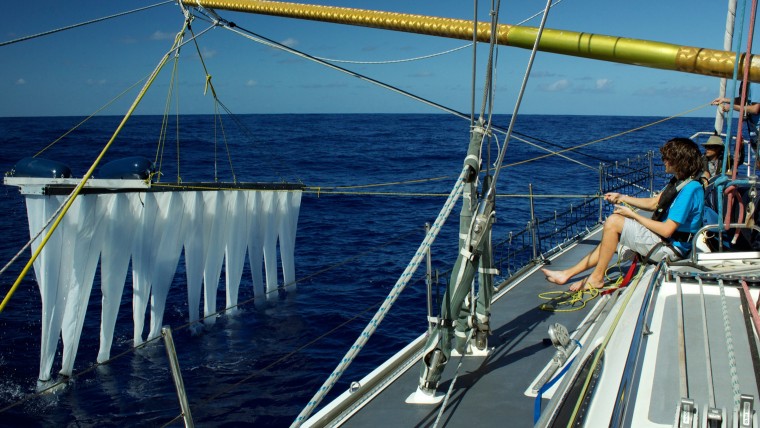

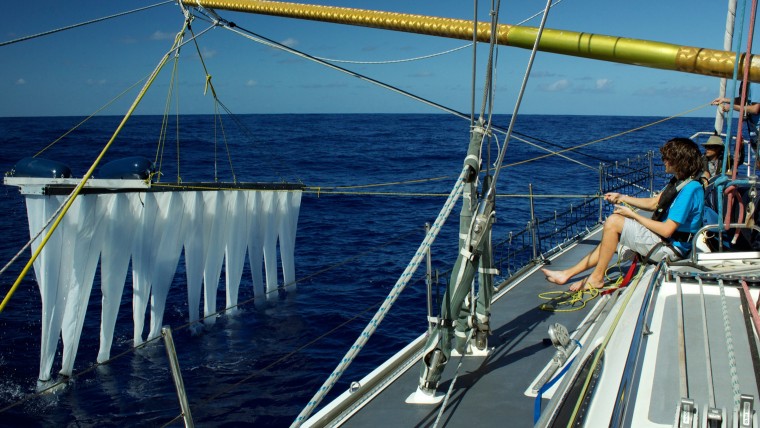

Preparing for deployment in three to four years, the Ocean Cleanup design principle asks why you need chase plastic expensively and ineffectively with boats and nets, when you can let it come to you. The proposal is for a single 100km scalable array of floating barriers or booms attached to the seabed. The ten-year clean-up targets passive removal of 42 per cent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, some 70,320,000kg at €4.53 a kilo.

Right now, the team are embarked on a mega expedition, with 50 vessels sailing from Hawaii to Los Angeles, generating measurements covering 3,500,000sq km.

The next objective will be to design and deploy the world’s first operational pilot array, 2,000m long, in coastal waters. Located off Tsushima Island, between South Korea and Japan, this will become the longest floating structure ever.

The big question is, of course, will it work? Doubts persist about the data and design. A number of critics, Ms Sun included, would prefer attention and investment directed towards prevention rather than cure, educating consumers to recycle and campaigning against single-use plastics. Mass beach clean-ups are championed as immediate, proven alternatives. Only engineering and time will tell. For now, inspiring innovation represents an achievable aspiration.

“Besides clean oceans,” concludes Boyan Slat, “I sincerely hope this project will have people dreaming big again about using our ingenuity to solve real problems.”