Today, Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium is a stronghold that plays host to Champions League matches, represents one of the toughest away days of the season for other Premiership clubs and has served as a home away from home for the Brazilian national side on seven occasions.

With a capacity of 60,260 and 150 executive boxes, it’s also a crucial element of the club’s financial health. In a sport where multi-million-pound losses in a single year are par for the course, match day revenues of £100 million – more than any other English club – have been crucial in allowing the North London club to buck the trend and record a profit of £27.4 million last year.

But it wasn’t always like this. Turn the clock back to the year 2000 and the Ashburton Grove site that the Emirates now occupies was home to around 100 different businesses and organisations, including a local authority waste disposal unit.

Getting the right team

Paul Mitchell, Arcadis

“At that point it was really just a pipe dream,” explains Paul Mitchell, the project manager from engineering consultants Arcadis, who worked alongside Sir Robert McAlpine, HOK Sport (now known as Populous) and Happold on the construction of the new stadium. “We started work on it 16 years ago, and you forget, but talking about it now, I’m reliving some of the nightmares and remembering the late nights.”

Of course, as we now know, the project was a success; finished on time and on budget. Something that Mr Mitchell says wouldn’t have been possible without first putting the right team together.

“The crucial things are having the right people in the right places to provide their expertise for their pieces of the development,” he says. “If you don’t pick the right team from the beginning, you’re battling it straight away. Invariably, it’s about the people; the people who have done it before, who have got the experience and are prepared to go the extra mile for the clients. That’s one thing we had, which very few projects ever get.

The club brought that whole winning philosophy through the project, so there was a fantastic team spirit

“At the time, it was actually mirrored by what was happening on the pitch,” adds Mr Mitchell. “Arsenal were winning the Premier League and FA Cup. The club brought that whole winning philosophy through the project, so there was a fantastic team spirit – and I’m saying that as a Tottenham fan.”

However, Mr Mitchell notes that a project manager who recruits the right people with the right attitude is far from guaranteed success. Timing is also key. “With a project of this size, you have to be cautious early on, because fees can run away with you quite quickly. Before you know it, the client could have spent millions and still not have anything that is buildable and viable. So you start off with a small core of expert people, then that grows as the teams within the individual companies get bigger and the whole thing becomes more likely to become a project.”

No one-size-fits-all model

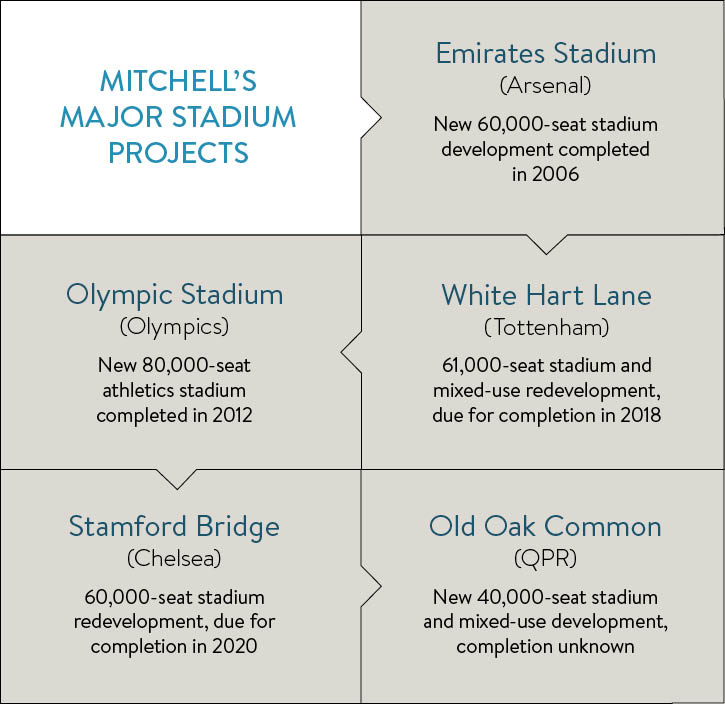

Other projects on Mr Mitchell’s CV include the Olympic Stadium at Stratford, East London, which like the Emirates, was delivered on time and on budget, as well as ongoing pieces of work for two of London’s other big football clubs. One of these is the redevelopment of Stamford Bridge that is expected to see Chelsea relocate to Wembley for three seasons until its completion in 2020. The other is the scheme to revamp Tottenham Hotspur’s White Hart Lane ground, which comes with its own particular challenges, including the requirement to temporarily remove the grass soccer pitch in order to expose an artificial American football playing surface that will be used for at least two NFL games each season.

As you might expect, Mr Mitchell says that when it comes to projects of this scale and complexity, there is no one-size-fits-all model that can be used to manage the various elements. “But that doesn’t mean the general principles aren’t often similar,” he says. “You have to plan it, you have to deliver it and there are a few standard things that we do. But it’s done project by project, to suit the particular nuances of each one.”

Stamford Bridge, home to Chelsea Football Club, is set to reopen in 2020 after redevelopment

The initial stage of project management is often as simple as drawing up some bullet points on an A4 sheet of paper. In the case of the Emirates, the bullet points might have been: “Procure the site; get planning permission; go out to tender; get a builder; construction period; finish the stadium; client learning and commissioning; handover and, finally, play the first football match.”

Then, as meat is added to the bones of the plan: “The documentation evolves and everything becomes more detailed. Sometimes flow charts are quite good to demonstrate processes and what we expect of people. Sometimes it’s bar charts. When you get into detailed construction, it’s usually gantt charts and virtually day-by-day programmes and planning.

“On the big megaprojects, you end up with various project managers on the team who will often use their own programmes and methodologies to deliver their piece of the jigsaw. That then feeds into the master plan – the whole picture evolves all the time,” says Mr Mitchell.

This hands-on approach to tackling the job perhaps explains why he places such little faith in formalised project management methodologies. “We’re not really into that stuff,” he says. “I’m sure that there are people who do it within our business, but in any of the big projects that I’ve been involved with it’s not used.” While the daily meetings stipulated by some project management methodologies might suit certain industries well, Mr Mitchell believes they don’t tend to work in construction where things are less immediate. Instead, he likes to encourage weekly meetings of the key leaders and then get the relevant people together to assess specific elements of the project as and when they are needed.

Work has already begun on the redevelopment of Tottenham Hotspur’s White Hart Lane ground

Changing plans

Of course, no matter what approach a project manager takes, it’s always possible for unforeseen events to force a change of plans. In the case of the Emirates Stadium, Mr Mitchell says he encountered no catastrophic problems, but he was involved in a decision to make a fundamental change to the design of the stadium.

Initially, the plan was for the stadium to be partly sunk into the ground. However, Mr Mitchell and his team worked out that in order to shift the earth that would have to be displaced, between 100,000 and 200,000 lorry journeys would have been required. The expense and logistical demands of that were assessed and it was decided that plans should change.

However, deciding to build the stadium at ground level would mean that its height exceeded the original plans. “And that’s why the roof slopes down,” he explains. “Often an issue that you come up against will have a knock-on effect. On complicated projects, so many issues are interlinked.”

This crease was ironed out early in the life of the Emirates project, but when incidents aren’t swiftly dealt with, they can often result in delays and, to compound the problem, negative media coverage. Is this something that can, or should, fall into the project manager’s remit?

“I don’t think what’s written in the press really affects us guys at project level,” says Mr Mitchell. “When something goes wrong or a project gets held up, there are usually a lot of complicated reasons for it that the people in the press don’t fully understand. Quite often the headline will concentrate on one thing that has gone wrong, but nine times out of ten, there will have been a chain of events leading up to that one thing which has been described as the cause of the delay or of going over budget.

“When the construction of Wembley was delayed, there were good reasons why. But the most important thing was that people stayed with the job and it got sorted out in the end. The way that these things get resolved is far more important than the negative press coverage about how they went wrong. You have to give credit to the people who ignore all these things and carry on so that they can get the project over the line. The Channel Tunnel was another one – you turn back the clock to 20 years ago and look how much of a slating the Channel Tunnel got, but everyone goes on Eurostar now and it has been forgotten.”

The role of tech

Since Mr Mitchell began his career as a surveyor back in the 1980s, he’s witnessed a number of changes. The most obvious of all has been the increased prevalence of technology. Even basic computers were hardly used at all at the beginning of his time in the industry. Today, of course, technology makes things easier in many respects, but Mr Mitchell isn’t convinced that its impact on project management has been universally positive.

“There are a lot of people now in project management who are process driven,” he says. “That can be good, but sometimes there are things that you have to leave behind and come back to later. That’s where the good guys carry it more in their brain rather than in their laptop.”

Another change, Mr Mitchell says, is the way that the industry has become far more collaborative. “It is the only way these megaprojects could ever get built,” he says. But this makes communication even more important and means that, if companies or individual people are ever tempted to hide behind the literal terms of their contract, things can quickly go wrong. “I suppose it brings us back to where we started,” says Mr Mitchell. “It’s all about the strength of the people and their keenness to get the project over the line.”

Getting the right team

No one-size-fits-all model