In high spirits the children from Gearies Primary School set off to take five adults with disabilities on a trip into central London. They had researched the route for wheelchair-accessible stations, but disaster struck at the first hurdle.

The gradient of the ramps and subways on the Central Line were too high for wheelchairs. At Newbury Park there was supposed to be a lift, but it hadn’t been installed. At Stratford the lift for disabled people wasn’t wide enough to take the wheelchairs.

So the pupils and teachers from the school in Gants Hill, north-east London, had to abandon the visit to a historic garden they had planned for friends at the Woodbine Centre for adults with learning disabilities.

Upset and disappointed, the 10 and 11 year olds decided to programme an app to help disabled people plan their journeys using mainly wheelchair-accessible buses. They tried out the routes and recorded them on tablets and smartphones to build an entry for the Apps for Good competition.

Because one adult could not read, they recorded verbal instructions alongside the photos and then provided pictures in sequence to help another with poor working memory. They made the final three in the contest, despite being some of the youngest entrants.

The digital classroom

Just three years ago it is unlikely that primary-age children would have been able to handle algorithms and content to build their own app, but schools have made great strides since September 2014 when a new computing curriculum was introduced.

The government changed the focus from being able to use technology to knowing how it works and coding. It also made computer science GCSE a contributing subject to the over-arching English baccalaureate for 16 year olds.

Walk into schools nowadays and most will have suites of laptops and tablets for use across curriculum subjects. From making comic strips of science experiments to video recording of cookery demonstrations and digital maths challenges, children are harnessing the tools of technology. IT has come out of the locked computer rooms to become an intrinsic part of teaching and learning.

Far from banning mobile phones in the classroom, some schools are using BOYD – bring your own device – to supplement resources, with children working on their own tablets and smartphones. Others are harnessing their pupils’ devices and home computers for the “flipped classrooms” whereby students access and study videos of the material they need to know before the lessons. It frees up time for students to explore the concepts and apply what they have learnt with the teacher in class, rather than doing it alone as homework.

The UK is doing well in the way it uses information technology to aid teaching and learning, says Caroline Wright, director general of the British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA).

Information technology has come out of the locked computer rooms to become an intrinsic part of teaching and learning

“We are one of the world leaders, particularly in digital content to support the curriculum. To give just one example, the Malaysian government wants to become the technology hub of South-East Asia and has decided the best way to do that is through partnership with the UK,” she says.

The UK hosts the annual BETT exhibition of education technology and more than a quarter of its expected 40,000 visitors next January will come from overseas.

Schools have come a long way since the 1990s when the main funding for computers came from vouchers parents collected with their food shopping. BESA’s annual reports show school spending on computer hardware and software in England has soared from £135 million in 1997 – slightly below the budget for stationery – to £616 million last year.

Budget constraints

There are signs that schools are struggling to maintain their ICT budgets, however. The National Association of Head Teachers (NAHT) claims there has been a reduction in overall education spending on schools this year of 7.9 per cent in real terms compared with 2011-12.

“As schools face rising costs, it is no wonder many schools report that budgets are at breaking point,” it says. The Department for Education disputes the figure, saying: “The schools budget has been protected and in 2016-17 totals over £40 billion, the highest ever on record.”

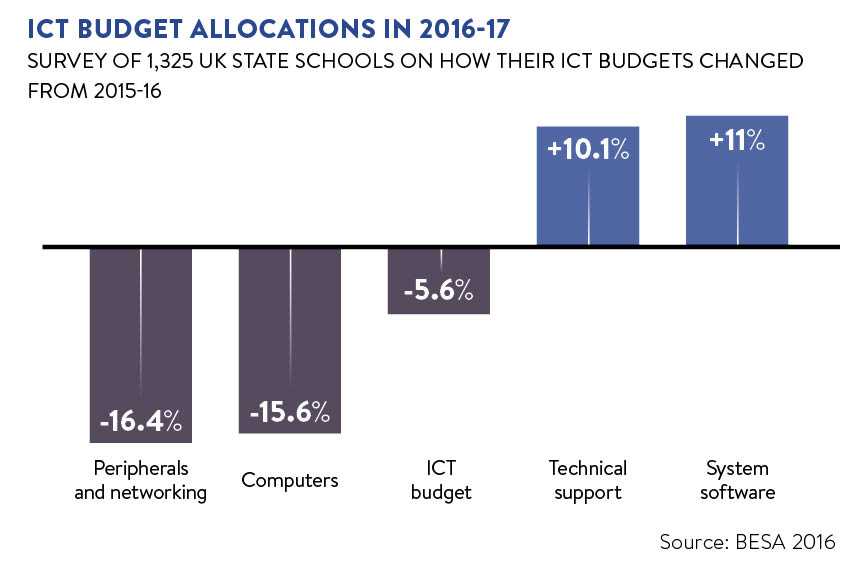

BESA also finds technology spending under pressure. Its 2016 survey found a quarter of schools had downgraded their planned ICT investments. It predicts that overall ICT budgets across all schools are likely to go down by 5.8 per cent in 2016-17.

Dan Lea, deputy headteacher of Gearies Primary School, says there is only £50 left in this year’s ICT budget of £18,000 for 710 pupils. “Funding is a problem for us at the moment. We have projects we would like to run, but we don’t have the money. We want to join the Childnet Digital Leaders Programme that trains pupils to be digital safety leaders because we think they will listen more to each other, but it costs £500. We’ve raised £315 from a raffle and are hoping to have a toy sale for the rest,” he says.

Teacher training

The effective use of ICT is not just about money. Training, especially for older staff, is crucial if children are to be prepared for the digital future, says Chris Woolf, headteacher of Pinner High School. “We are a new school and one of the things that makes us different is that we are not adapting to a wireless future, we are setting up a wireless future. Sometimes people get hung up on the hardware, but it’s more about the communication and collaboration that it allows,” he says.

“We have books on a reading cloud, use an online homework app and encourage pupils to work together to edit material online and communicate with students from schools in other countries.”

NAHT adviser Siôn Humphreys says the initial surge of interest and enthusiasm for the new computing curriculum has plateaued. “Those teachers who were tech savvy were early adapters. The challenge now is to get all teachers involved. But technology isn’t always the best method – to use a golfing analogy, teachers have to use the right club at the right time,” he says.

Futurists tell us that it won’t be long before our brains can be “chipped” with information, making much of the school curriculum redundant. For now, however, schools are concentrating on keeping pace with technological advances and the new ways their “digital native” pupils are finding to use them.