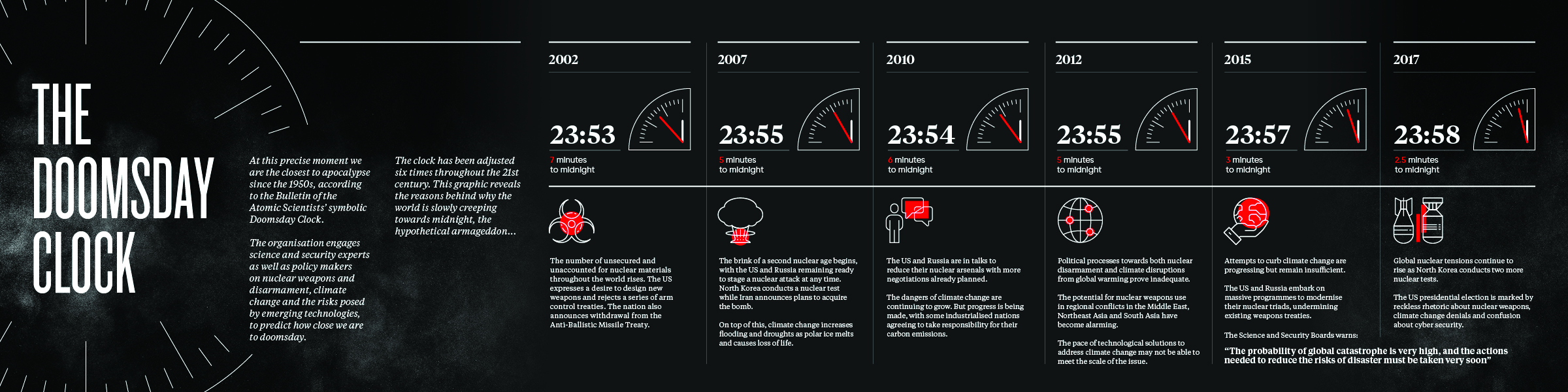

At this precise moment we are the closest to the apocalypse since the 1950s, a twitchy period when Cold War combatants, the United States of America and the Soviet Union, were doggedly pursuing the hydrogen bomb. At least that’s according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ symbolic Doomsday Clock, which sparked global alarm when it ticked forward to two-and-a-half minutes to midnight in January.

More worrying still, the 2017 time setting was determined before North Korea’s recent spate of nuclear missile tests, and climate-change denier Donald Trump’s erratic presidency, which has re-chilled Russian-American relations, had begun in earnest.

Indeed, as the iconic Doomsday Clock – a simple design depicting a minute hand nearing a hypothetical midnight armageddon that neatly captures experts’ level of anxiety about technologies which could destroy humanity – turns 70 this May, its message has never more potent, or relevant.

“After carefully considering a number of factors, including nuclear weapons and disarmament, climate change, and the risks posed by emerging technologies, our Science and Security Board (SASB) took no pleasure in pushing the minute hand of the clock forward 30 seconds from three minutes earlier this year,” Rachel Bronson, executive director of the Bulletin tells Raconteur.

“Given that the Doomsday Clock is set by the Bulletin – a Chicago-based organisation that engages science and security experts, policymakers, and the interested public on existential threats – there is an understandable expectation that our assessment, reached after months of considerable debate, is founded upon wise judgement. That the time in 2017 is the nearest to midnight in 70 years – bar the 1953-59 period [when it remained at 11.58pm] – is a big deal, and has triggered more worldwide reaction than usual.”

In early May, the Bulletin published its annual report which revealed record-breaking numbers of website hits, as well as email newsletter and magazine subscriptions, in the calendar year through January 2017. Further, the organisation’s Twitter account attracted 84 per cent more followers (currently 28,000, and rising), while the video of the Bulletin’s press conference announcing the 30-second move from three minutes to midnight had been watched by more than 2.5 million people.

“In 2016, NASA reported the warmest year globally since modern record-keeping began,” began Lee Francis in the annual report’s opening letter from the chair. “Worldwide nuclear tensions increased as relations between the United States and Russia continued to deteriorate, and North Korea conducted two underground nuclear tests. The divisive 2016 US presidential election was marked by reckless rhetoric about nuclear weapons, climate change denials, and confusion about cyber technology and artificial intelligence.

“Through it all, we … stepped up our programming and added features to our website attracting more visitors, subscribers, and donors than ever before in more than seven decades of service. Keenly aware of growing uneasiness and concern, we maintained a sharp focus on nuclear issues, climate and energy, and threats from emerging technology, bringing together the best scientific research and public policy analysis in the hope of creating a safer and healthier planet.”

The history of the clock

The Bulletin was established in 1945, shortly after the World War II-ending atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, by a cluster of scientists who had worked on the Chicago-based Manhattan project and were terrified by the evolution of their work. “They felt nuclear weapons should never be used again and that civilians and policy makers needed to be engaged in a different way to understand the risks of the technological advancement,” explains Bronson. The group produced a six-page, black-and-white journal to circulate and educate, and Albert Einstein, no less, wrote the fundraising letter to help launch their efforts.

“In the early days, there was one technology which had the power to electrify and destroy the world: nuclear,” continues Bronson. “The thinking was that if we could manage the significant risks, the upsides were considerable. And that has been what the Bulletin has always been about: managing the risks associated with new technologies so that we can benefit from scientific advancement.”

The proximity of nuclear devastation was a popular concern 70 years ago. And in 1947, when the Bulletin upgraded to become a magazine, Martyl Langsdorf – the landscape-painting wife of physicist Alexander Langsdorf, Jr., one of the founding members – volunteered to create the first cover, for the May-June edition. Despite a prohibitive budget that demanded no more than two colours and with limited space for illustration she invented the celebrated Doomsday Clock image.

Langsdorf set the original time at seven minutes to 12AM, because “it looked good to my eye”. The Bulletin has reset it 22 times since then; in 1991, at the end of the Cold War, it moved back to a record 11.43pm, and January’s 30-second advancement from three minutes to midnight is the most recent.

“I love the simplicity of the Doomsday Clock, and believe it is one of the most powerful examples of art and science coming together,” says Bronson, who took on her role at the Bulletin in February 2015. “It cleverly highlights a countdown to danger while provoking a sense of urgency to act responsibly for the good of mankind.

“The analogue clock is a dusty, old concept, but without fanfare it helps people ask and answer whether the world is safer, or in greater danger, than it was compared to the last year, and the last 70 years.”

With luck, Donald Trump’s presidency will be short lived so that we can take action on climate change at a national level once more

In 2007, when New York design consultancy firm Pentagram was approached by the Bulletin to devise a new logo for the organisation, Michael Bierut wasted no time in recommending the Doomsday Clock, which he describes as “the most powerful piece of information design of the 20th century”. It is, to his mind, a prime specimen of information design, or a graphic communicating complex data.

“We suggested that the logo should be based on their most well-known visual asset: the clock face,” Bierut, a venerated graphic designer and partner at Pentagram, says to Raconteur. “The Doomsday Clock takes a vast array of information and analysis about the proliferation of nuclear and chemical weapons, climate change, and political conflict, and reduces it to a simple metric: the number of ‘minutes’ we have left as a species. It is as powerful a statement as you can imagine.

“The metaphor of the ‘ticking time bomb’ is one of the most enduring dramatic devices in the world. Without words, it communicates a sense that time is running out, which is exactly the message that the Bulletin is trying to convey.”

Climate change challenge

In 2006 the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board (SASB) was asked, for the first time, to factor in the threat of climate change before setting the Doomsday Clock. “It was a controversial move,” says Bronson. “The impact timescales of nuclear and climate risk are clearly different, with the former being immediate and the latter slow rolling. They are apples and oranges, but to answer the key question – ‘is the planet safer or at greater risk than it was last year?’ – we have to bring together apples and oranges.

“Now emerging technologies, such as cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and biosecurity are also beginning to feature in our Doomsday Clock statement, though not in a way that has yet to alter the time.”

Sivan Kartha, senior scientist in Stockholm Environment Institute’s US Center and an expert on climate change policy who has advised the United Nations and a variety of governments, “happily accepted” his invitation to join SASB five years ago, having read the Bulletin since his graduate-school days at Cornell University in the late 1980s. Currently, there are 14 members sitting on the board, all preeminent scientists or security luminaries, who meet twice a year, and Kartha says their task to set the Doomsday Clock is becoming increasingly tricky.

“The clock is a metaphor for how dire the situation is, and – especially adding climate change in the mix – it’s such a complex assemblage of different issues with their own timescales that we’ve definitely made the job not qualitatively different, but just more challenging,” he tells Raconteur. “Climate change is a global problem, and it has to be solved by global cooperation. Therefore, it can only be done in a way that’s fair and so that different countries feel it works for them. We need a climate regime that ambitiously moves forward as opposed to muddling along.”

With this in mind, the election of President Trump – a vociferous critic who has repeatedly labelled global warming a “hoax” and in early June angered allies by abandoning the 2015 global pact signed in Paris to fight climate change – is troubling for Kartha and his Bulletin colleagues.

“It is certainly a setback,” he continues, wryly. “Although, in 2001, President George W. Bush was a denier as well, and antagonistic to the idea of climate action. As there was paralysis at the national level the action fairly rapidly shifted down to the state and city level. We can expect the same thing to happen this time around.

“However, Trump is actively trying to do worse than inaction: he’s trying to undo actions of Barack Obama’s administration. No doubt that will be harmful. So hopefully we’ll see action continuing on climate change, just at a different level in America. And with luck, Donald Trump’s presidency will be short lived so that we can take action at a national level once more.”

Members of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists deliver remarks on the 2017 time for the “Doomsday Clock” January 26, 2017 in Washington, DC. From left to right are Executive Director and Publisher of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Rachel Bronson, theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss, former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Thomas Pickering and retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral David Titley. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Nuclear weapons

Similarly, Bronson laments that President Trump’s “casual approach to the subject of nuclear weapons, and dismissiveness about climate change” during his election campaign has not been shackled now he is incumbent. “Words and expert opinions really do matter, because miscommunications and misconceptions from those in high office can be devastatingly dangerous,” she warns. “We now have a very inexperienced leader who has been clear that he makes his decisions from the gut, and on limited advice.”

The metaphor of the ‘ticking time bomb’ is one of the most enduring dramatic devices in the world

Another impulsive global player is North Korea’s 33-year-old supreme leader Kim Jong-un. His country’s three ballistic missile tests, fired into the Sea of Japan, pockmarked April and provoked increasingly angry reactions from President Trump. They also prompted emergency SASB action; would they nudge the Doomsday Clock forward in a seldom-witnessed mid-year move?

“This April the Bulletin’s website attracted double as many unique users compared to 12 months earlier, and we could actually tell when the missile tests had happened because of the traffic spikes,” says Bronson. “We received a lot of email and Twitter messages – some of them very angry – pointing out that we could be on the precipice of a nuclear conflict and [the Doomsday Clock] is set at two-and-a-half minutes to midnight.

“I had an exchange with the board, to double-check that the Doomsday Clock was set correctly. The members were clear that everything that we were seeing with North Korea had been baked into the current time. We don’t move the Doomsday Clock for individual actions, but it’s true that North Korea’s testing was the kind of example – of a country on an unabashed programme to increase their nuclear arsenal – that we had feared.”

Turning back time

While Kim plots his next dubious launch, the appeal of Martyl Langdorf’s Doomsday Clock endures. In early June an exhibition entitled ‘Turn Back the Clock’ opens at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, to commemorate its 70th anniversary. “While the gravity of the clock’s influential factors are sobering, we want people to understand that agency, communication and collaboration can truly make an impact,” project director Patricia Ward tells Raconteur.

“The exhibition follows a three-part narrative: the dawn of the nuclear age; the clock as a metaphor for the challenges the world faces in dealing with nuclear weapons and climate change; and finally, the state of the world in the 21st century, and where we are headed with emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and new biotechnologies,” she explains. The overarching question is: what will you do to move the minute hand backwards?

Interest in the Bulletin has, well, mushroomed in 2017 – and only partly as it is the Doomsday Clock’s 70th birthday. Paradoxically, it is because the global overview is so “scary and terrible”, states Bronson. “In this time of ‘fake news’, we want to make sure people are engaged with the right information, and come to us for the facts,” she says, pointing out that nearly half of the website visitors tune in from outside America, and also 53 per cent of the online audience are under the age of 35, with 70 per cent younger than 45.

“We feel an enormous sense of responsibility, in a positive way,” Bronson adds. “There is an integrity and carefulness with which we put the material out in front of a motivated and mobilised population, and it’s gratifying to be able to connect the right experts with an engaged audience anxious for information.

“Our ultimate aim is to send out the message that we as citizens and individuals can move the clock back as well let it tick forwards, and we all have a responsibility to manage the risks of scientific advancement, which will enrich our lives, if approached responsibly.

“If we can help galvanise that attention and support then we have done a good thing. Hopefully enough people will listen and engage, so we can push the clock back further away from midnight in 2018.”