When she stood in Downing Street to make her first speech as prime minister, Theresa May gave an impassioned vision of a more inclusive nation. “We believe in a Union not just of the nations of the United Kingdom, but between all of our citizens. Every one of us, whoever we are and wherever we are from,” she said, talking about, “the mission to make Britain a country that works for everyone.”

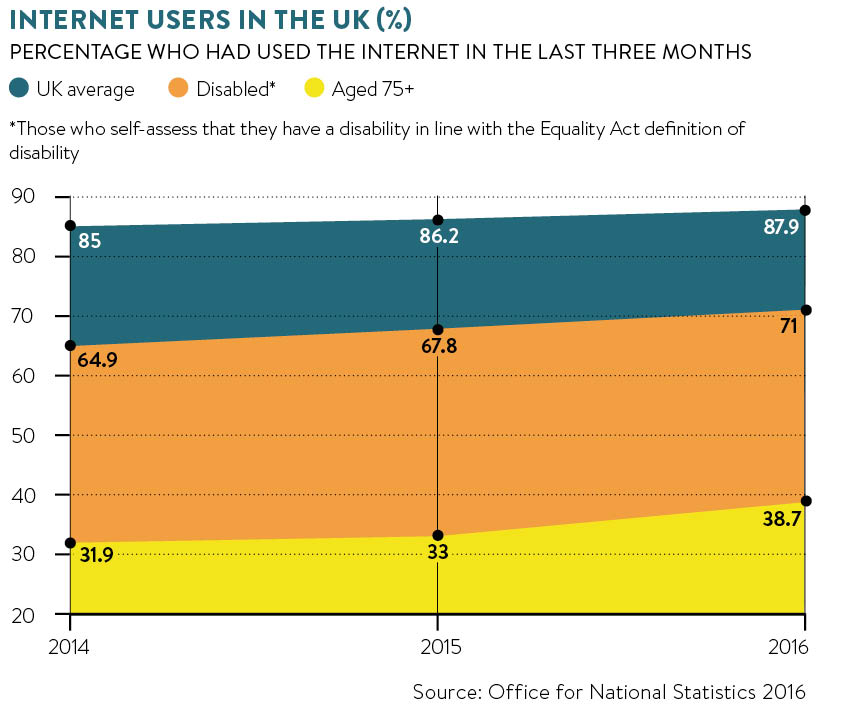

Mrs May didn’t actually mention the internet, but given that it affects every aspect of our lives these days, the issue was perhaps implicit. Certainly, in recent years efforts have been made to open up the digital world to those from poorer backgrounds, and people with disabilities and educational difficulties. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines are part of a series of advice published by the Web Accessibility Initiative, which is part of the World Wide Web Consortium, the main international standards organisation for the internet.

These guidelines specify how companies, organisations and government should make content accessible, primarily for people with disabilities. In the UK the last government launched its Digital Inclusion Strategy in 2014 with the aim of partnering with the public, private and voluntary sectors to reduce the number of people without basic digital skills and capabilities by a quarter.

The strategy identified four main obstacles. The first is access, in other words the ability to actually go online and connect to the internet. Online skills are second, followed by motivation or understanding why using the internet can be a good thing and, finally, trust or in other words concerns about cyber crime and safety. The success of the project will be reviewed this year.

Closing the digital divide

The initiative aims to counter what is known as the “digital divide”. Although this phrase is often used to refer to physical access to the net and broadband skills, campaigners also apply it to inequality of internet skills. You can have super-fast cable, but if you don’t how to search for a good local dentist or where to find the necessary information for a job application, then megabytes per second are irrelevant.

Recent research by the BBC revealed that around one in five (21 per cent) of the UK population lack the basic digital skills necessary to benefit from the internet. According to a study by Dr Ellen Helsper of the London School of Economics (LSE) and Dutch researcher Dr Alexander van Deursen, educated people on high incomes derive the greatest benefits from using the internet, getting better deals online for products and holidays, using the internet more successfully to expand their social life and becoming more informed.

While more and more people might be online these days, the internet clearly benefits those with a higher social status

In contrast, low-income people from socially deprived backgrounds do not receive the same benefits, regardless of access. The study of more than 1,100 people was conducted in the Netherlands, a country with a well-developed digital infrastructure and near-universal access. Disabled people, along with retired and unemployed individuals and care-givers, receive the fewest benefits overall by being online. According to the LSE research, 12 per cent of people don’t know how to go back to the previous page.

“Governments and others have focused too much on pipes and infrastructure, and have taken the ‘build them and they will come’ approach, but that’s not the case. There is a risk of a digital underclass. Access to and use of the internet might exacerbate existing inequalities offline,” says Dr Helsper. “While more and more people might be online these days, the internet clearly benefits those with a higher social status.”

In the United States there have been a growing number of high-profile court cases in which large organisations have been successfully sued for millions of dollars because their sites are deemed to be inaccessible and therefore contrary to US law.

Online access for disabled

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are most at risk of either being subject to legal action or simply losing business from what the Department for Work and Pensions calculates is a disability market worth £212 billion. “SMEs are not intentionally excluding these customers – some have just not explicitly considered their needs,” says Adam Rowse, head of business banking at Barclays Bank. “Unlike a shop where it’s obvious to see the challenges that disabled or older customers face entering, getting around and paying for stuff, it’s less obvious for an online shop.”

He cites new research from the Click-Away Pound Survey, which is designed to explore the online shopping experience of people with disabilities, showing that 71 per cent of disabled people with access needs who shop online chose to click-away from a site that presented barriers in favour of finding a more accessible one.

“Technology has provided massive opportunities for people with disability and massive opportunities for companies, service providers and government to serve them,” says Steve Tyler, head of solutions, strategy and planning at the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB).

Blind himself, Mr Tyler controls his music system at home through an app on his iPhone. He shops on Amazon, Ocado and John Lewis through an accessible app or website, as well as buying coffee with an app that delivers an accessible receipt. “Today websites can be written in such a way that specialist technologies like screen-readers that render websites into speech or magnify the site can access them,” he says.

The charity runs a project called Online Today, which aims to provide digital skills to 125,000 people with sight or hearing loss, or both. Internet use by those who need enhanced accessibility mirrors that by the wider public, except that the age difference is even more pronounced. According to recent survey by the RNIB, while almost two thirds of those aged 75 did not use a computer, the internet, a tablet or a smartphone, 86 per cent of 18 to 29 year olds said they could make the most of new technology. The majority of people who do not currently use technology, the survey reported, would like to use it if obstacles were removed.

The trend implied by these findings is positive – the challenge for companies, government bodies and other organisations is to take a long hard look at their online presence and make sure they’re playing their part.