Renewable energy used to be deemed unaffordable for developing countries. Wind and solar were rich country luxuries, while third world economies could only be expected to grow on a diet of dirty fossil fuels. As recently as June 2014, Bill Gates blogged: “Poor countries… can’t afford today’s expensive clean energy solutions and we can’t expect them to wait for the technology to get cheaper.”

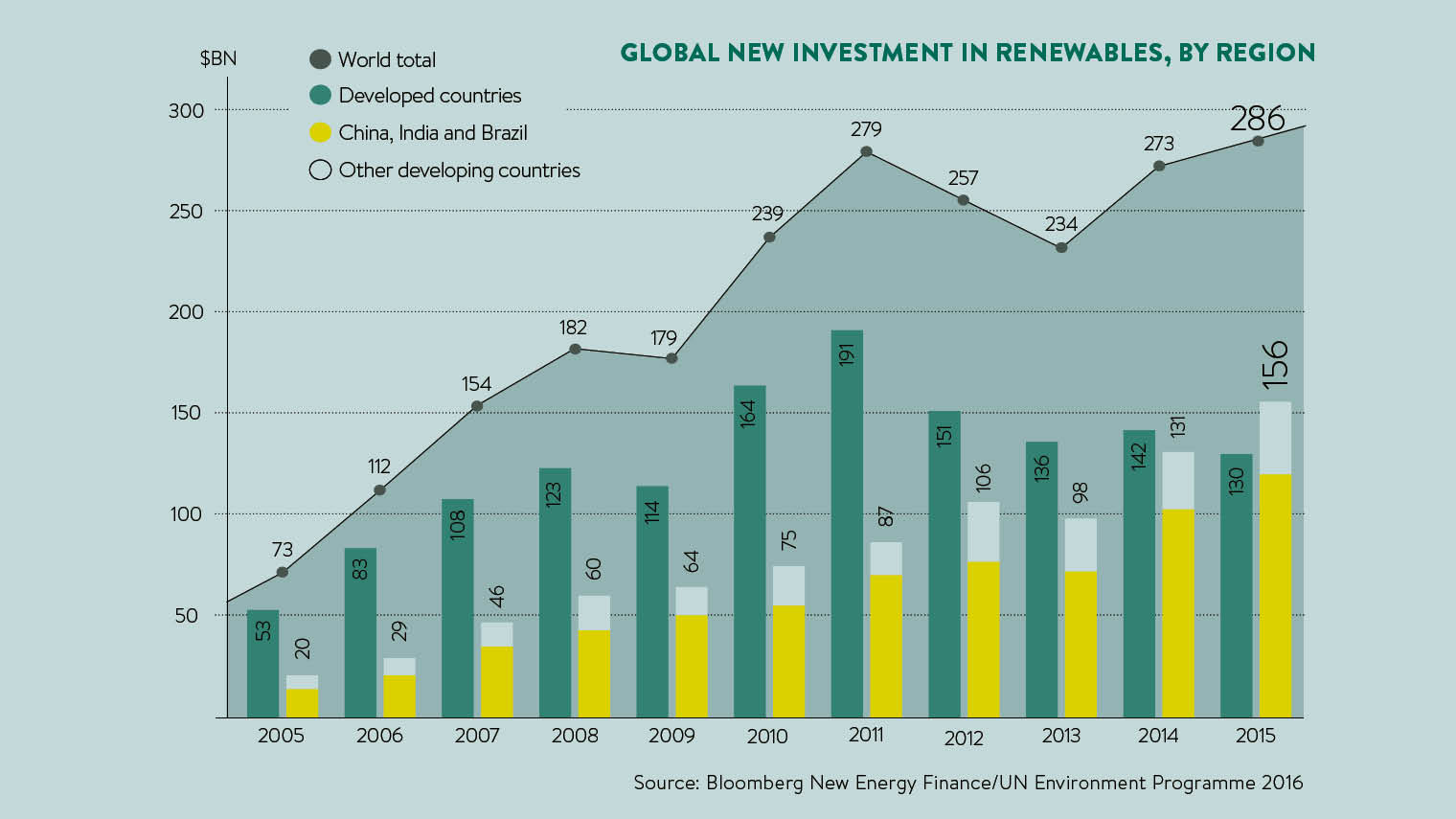

However, the past two years have seen this received wisdom turned on its head. Latest figures from the United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) show that in 2015 total clean energy investment in developing countries actually surpassed that of developed countries for the first time at $156 billion compared with $130 billion.

For the full infographic click here

Taking the lead

The biggest renewable investors included Chile ($3.5 billion, up 157 per cent) South Africa ($4.5 billion, up 329 per cent) and Morocco ($2 billion, up from almost zero in 2014). India saw investments rise 22 per cent to $10.2 billion while China, now the world’s biggest investor in renewable technology, spent $102.9 billion on renewables (36 per cent of the world total).

If you consider investments relative to annual GDP, the top five investors globally were actually Mauritania, Honduras, Uruguay, Morocco and Jamaica. Meanwhile, Costa Rica is remarkably close to becoming the first developing country to have 100 per cent renewable electricity.

“Wind and solar power are now being adopted in many developing countries as a natural and substantial part of the generation mix,” says Michael Liebreich, chairman of the advisory board at BNEF. “They can be produced more cheaply than often high wholesale power prices; they reduce a country’s exposure to expected future fossil fuel prices and, above all, they can be built very quickly.”

While Europe is looking to more expensive offshore wind options to appease not-in-my-back-yard voters, many developing countries are happy with cheaper on-shore and solar options. This in turn means the companies selling those technologies are increasingly looking towards emerging markets. Total renewable investment in Europe actually slipped 21 per cent to $48.8 billion in 2015 and today’s growth market is in the global south.

Kirsty Hamilton, an expert in renewable energy investment at Chatham House, outlines the mix of factors at play, including cost-reductions, strong government policies and investors actively looking for opportunities. The big European projects, such as Germany’s Energiewende, may have driven the growth in renewable energy technology, says Ms Hamilton, but recent political flip-flopping has seen investors “head to the least risky countries”.

Harnessing solar energy

India’s prime minister Narendra Modi launched a global solar alliance at the Paris climate conference in December, with his own country aiming to increase solar installations from just below 5GW to 100GW by 2022. To put that into perspective, the UK’s entire nuclear capacity is currently 10GW. This would be more than double the present solar capacity of current global leader China.

The project might sound far-fetched, but it is already underway. SB Energy, a joint Japanese-Taiwanese venture, recently won a bid for a 350MW project in India’s Andhra Pradesh province. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis describes India as “executing one of the most radical energy sector transformations ever undertaken”.

Developing countries can now afford renewable energy and the major energy corporations can’t afford to miss out on these growth markets

Ronan O’Regan, director of renewables at PwC, believes that for net importers of fossil fuel such as India, investing in renewables is economically and politically attractive in developing countries. The cost of renewables generation also continues to fall, particularly in solar photovoltaics. In the second half of 2015, the global average cost of solar PV was $122 per MWh, down from $143 in 2014. Wind is even cheaper, at $83 per MWh in late-2015 compared with $96 per MWh in 2009.

Developing countries can now afford renewable energy and the major energy corporations can’t afford to miss out on these growth markets. “It is a logical play for the renewables businesses to start to look much more expansively in terms of geographies,” says Mr O’Regan.

Development banks

In the early-2000s, Italian-headquartered Enel, one of the biggest energy companies in the world, was focused on fossil fuel generation in the northern hemisphere. Since 2009, however, it has transformed into the world’s largest producer of renewable energy, with the majority of new business coming from emerging markets. Its 2016-19 strategic plan commits around 50 per cent of investment to renewables in emerging and developing markets.

Enel’s chief executive Francesco Starace says: “Mature markets such as Europe are affected by oversupply and flat, if not decreasing, electricity demand. On the contrary, an increasing number of emerging countries are discovering the benefits of renewables and attracting new investments. They are faster to build and easier to operate. On average a typical wind project can be completed in 12 to 18 months, versus four to five years for a coal-fired plant of a similar size.”

This is very attractive to investors of all sizes. He says: “Emerging and developing markets alone represent a $5-trillion potential market, of which more than $300 billion is expected to go to the energy sector.”

Development banks have also played a part in getting large-scale projects up and running. Mexico, for example, has been helped by funding from development bank Nafin for nine wind projects. The Efeler geothermal plant in Turkey also received $200 million from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, while the International Finance Corporation loaned the money to build a 36MW wind farm in Jamaica.

“Development banks have an important role to play in terms of providing liquidity,” says Mr O’Regan. “They go into projects first, take a bit more risk, help to make projects bankable and that gives confidence to local commercial investors to co-fund on projects and who themselves gain knowledge and understand the risks. So by the next project, you no longer need the development bank.”

It is a role they may not need to play for long. Stock market investors and venture capital are already moving into renewables projects in emerging markets. In Uruguay, one of South America’s leading wind markets, 2015 saw equity raised on the Montevideo stock market to help finance local wind projects. While Indian renewable energy companies attracted $548 million in venture capital and private equity funding in 2015.

“Investments in renewables are today almost exclusively market driven,” says Enel’s Mr Starace. “Initially governments, by establishing renewables targets and feed-in tariffs mechanisms, played a key role. However, the private sector has spearheaded this revolution.”

As for the specific types of renewable technology that developing countries are investing in, solar and wind are the top two by far, at $80 billion and $60 billion spent in 2015 respectively. Small-scale hydro is the only real significant other at $4 billion. The likes of biomass, biofuel, waste-to-energy and offshore wind remain of more interest to wealthier nations.

“There are not that many geographies that are pursuing offshore wind,” says Mr O’Regan. “It is significantly more expensive than onshore wind. If you were advising a developing country on their renewable energy strategy, even if you had access to sufficient offshore resource and the ability to grid-connect, it would still be one of the last things you’d look at.”

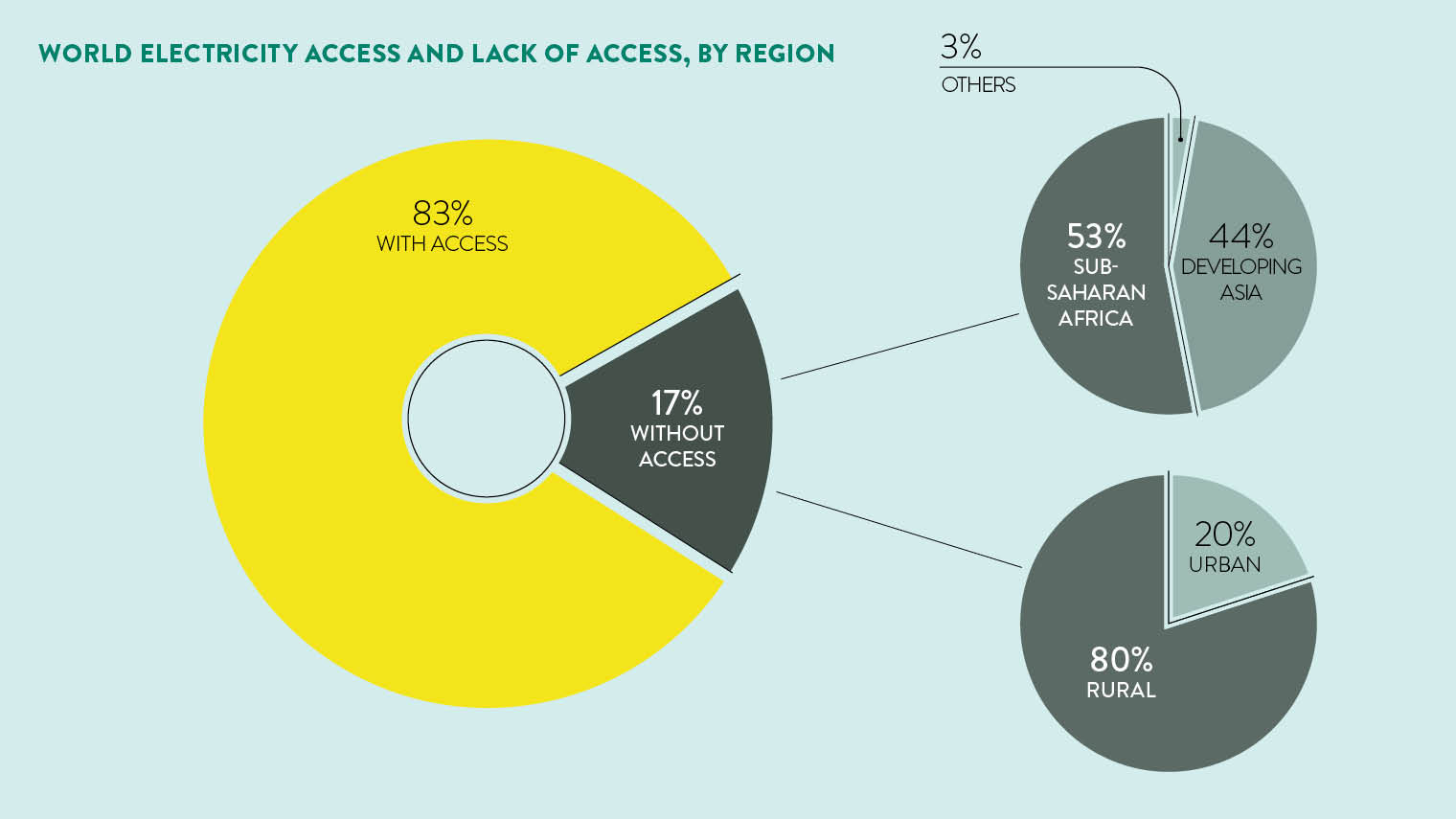

There is also a success story of off-grid micro generation rapidly spreading through the developing world. Some 89 million people in Africa and Asia already own at least one solar-powered product, according to the World Bank Group; about 15 million off-grid households will have solar-powered TVs by 2020. West African mini-hydro options could soon provide up to 70 per cent of rural electricity.