If you’ve had some keys cut or shoes repaired in the past decade, there’s a good chance you’ve been a customer of John Timpson. He’s the chairman of the Timpson chain, found in almost every shopping centre and high street across the UK. And now this modest man is Sir John, though it’s not clear which of his many good works earned him his recent trip to Buckingham Palace.

He’s a phenomenal businessman. His company has 1,600 stores and is reliably profitable. He’s a great thinker. The company is run with his “upside-down” philosophy, which gives autonomy to store managers to decide how their domain is run. He’s an extraordinary citizen and with his wife Alex, now Lady Timpson, he fostered 90 children, which was cited in his knighthood. And he’s a philanthropist.

For many years the Timpson company has employed ex-prisoners. Sir John is the author of the guide How Prison Leavers Can Find A Career. He opened premises behind the walls of Liverpool Prison. The scheme trains dozens of new employees a year in the art of key-cutting and cobbling. The company is regarded as a model for getting prisoners back into productive and enjoyable employment.

That’s not all. The company offers a free suit-cleaning service for anyone unemployed with a job interview. Fund-raising by employees has raised more than £2 million for the charity Childline. And Sir John is a vocal advocate of helping others in business, sharing his lessons with countless young entrepreneurs.

Companies are moving fast to rectify problems in their own sectors and within society as a whole

Now here’s the question. Is Sir John unusual? He’s a one-off personality, clearly. In fact, his ethos that companies can improve society via more than their profit and loss is going mainstream.

Companies are doing the work governments are supposed to handle. In education, combating climate change, demanding better working conditions in emerging markets – these are just some of the areas where the private sector is filling in the gaps left by the state.

Education is a great example. Indian engineering giant Tata, which owns Jaguar Land Rover, is committed to ethical business practices and runs an astonishing range of schemes to help children learn about science. Its programme in the Netherlands introduces technology to schoolchildren. It runs the Kids of Steel programme for eight to thirteen year olds to promote healthy lifestyles. The reason? It harks back to founder Jamsetji Tata, father of Indian heavy industry. He advocated a commitment to the local community beyond mere profit and loss. It’s an ethos taught to Tata executives today.

Spanish telecoms group Telefonica runs educational programmes in multiple territories. In Peru it offers an online portal, publishes materials for teachers and provides tuition to children in hospitals; over 16 years, the scheme has helped 55,000 children in 11 hospitals.

The environment is a growing concern for big businesses. Car hire firm Avis and media company Sky are just two of the many carbon-free businesses.

Working conditions used to be a governmental issue. Now companies are taking action. US coffee chain Starbucks ensures its supply chain is accredited by Conservation International. Marks & Spencer has its own human rights policy for suppliers.

The appetite to be recognised as a responsible business has given rise to two official standards in business.

The first is what’s known as integrated reporting (IR). This is an accounting approach which includes all secondary information relevant to the company’s long-term story, including the “six capitals” of financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural. Investors can therefore make a more informed decision around the prospects of a company.

IR was introduced in 2013 and backed by organisations such as the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants. This is significant as these bodies are renowned for their rigour. Wishy-washy mission statements won’t cut it. IR is a global initiative, used by every company on the South Africa stock exchange.

The second strand is environmental, societal and governance (ESG) investing. Companies investigate these three elements and report any impact, positive or negative. They are expected to take action to mitigate the negative. It’s a huge factor in global investing.

Larry Fink, chief executive of BlackRock, the US asset manager with $5 trillion in funds, wrote last year about the need for businesses to embrace ESG reporting. In a letter to chief executives at S&P 500 companies and large European corporations, he said: “Generating sustainable returns over time requires a sharper focus not only on governance, but also on environmental and social factors facing companies today.”

Larry Fink, chief executive, BlackRock

If there was any doubt, he stressed that investors would demand ESG reporting as it reduces risk from misbehaviour and correlates with clearer strategy. “At companies where ESG issues are handled well, they are often a signal of operational excellence. BlackRock has been undertaking a multi-year effort to integrate ESG considerations into our investment processes and we expect companies to have strategies to manage these issues,” wrote Mr Fink.

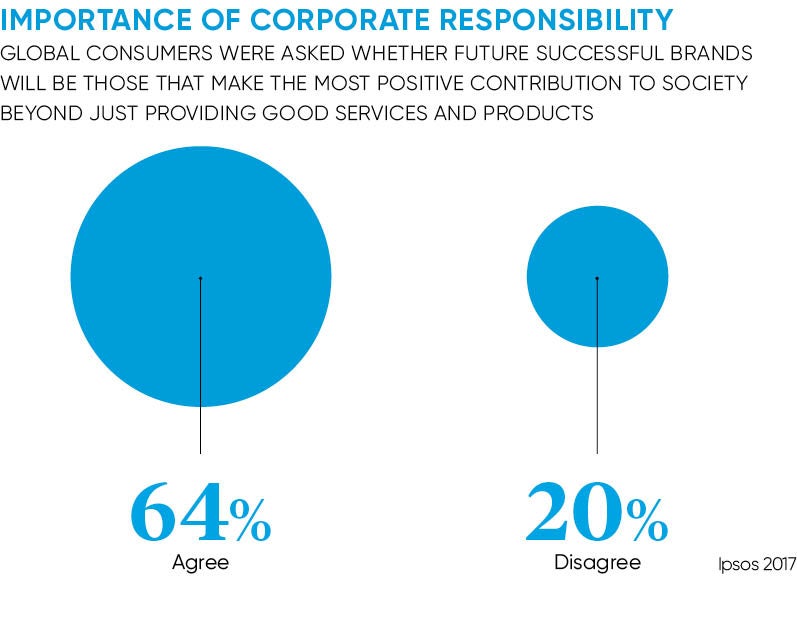

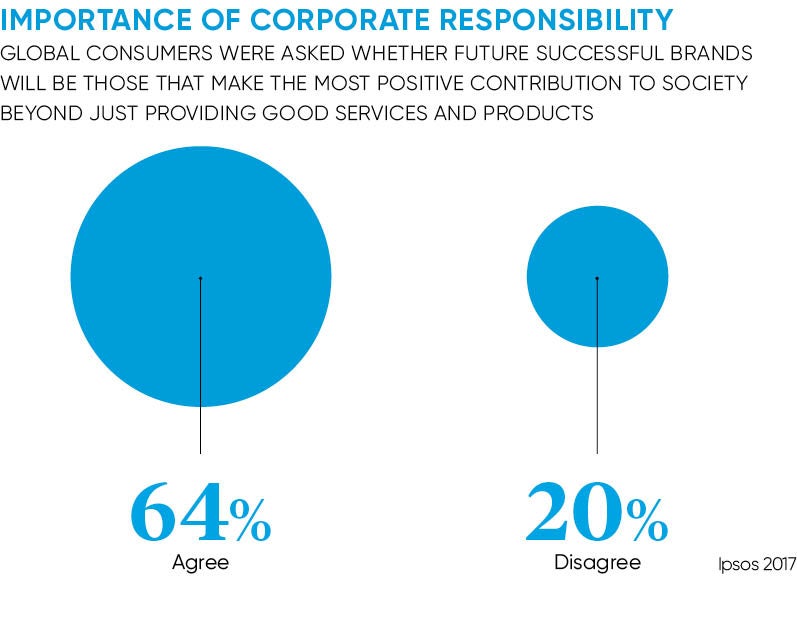

The headline is that companies are moving fast to rectify problems in their own sectors and within society as a whole. The public supports the move. A global survey by Ipsos found strong approval for brands which make contributions beyond just providing good services and products, averaging 68 per cent in favour compared with 20 per cent against. In emerging markets, where environmental issues and labour relations are hot subjects, this rose to more than 80 per cent: 86 per cent in Indonesia, 83 per cent in India and 80 per cent in China. Even the Pope has chipped in, calling unbridled capitalism “the dung of the devil”.

Saintly characters like Sir John Timpson are proving the private sector can contribute to social causes. Commercial performance need not suffer for ethical ideas. To the contrary, customers will reward it. And investors will increasingly demand it.